Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Spring 2015, Vol. 24, No. 1

Content

- California Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law and Federal and State Procedural Law Developments

- Chair's Column

- Editor's Note

- How Viable Is the Prospect of Enforcement of Privacy Rights In the Age of Big Data? An Overview of Trends and Developments In Consumer Privacy Class Actions

- Keynote Address: a Conversation With the Honorable Kathryn Mickle Werdegar, Justice of the California Supreme Court

- Major League Baseball Is Exempt From the Antitrust Laws - Like It or Not: the "Unrealistic," "Inconsistent," and "Illogical" Antitrust Exemption For Baseball That Just Won't Go Away.

- Masthead

- Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide: In the Age of Big Data Is Data Security Possible and Can the Enforcement Agencies and Private Litigation Ensure Your Online Information Remains Safe and Private? a Roundtable

- Restoring Balance In the Test For Exclusionary Conduct

- St. Alphonsus Medical Center-nampa and Ftc V St. Luke's Health System Ltd.: a Panel Discussion On This Big Stakes Trial

- St. Alphonsus Medical Center - Nampa, Inc., Et Al. and Federal Trade Commission, Et Al. V St. Luke's Health System, Ltd., and Saltzer Medical Group, P.a.: a Physicians' Practice Group Merger's Journey Through Salutary Health-related Goals, Irreparable Harm, Self-inflicted Wounds, and the Remedy of Divestiture

- The Baseball Exemption: An Anomaly Whose Time Has Run

- The Continuing Violations Doctrine: Limitation In Name Only, or a Resuscitation of the Clayton Act's Statute of Limitations?

- The Doctor Is In, But Your Medical Information Is Out Trends In California Privacy Cases Relating To Release of Medical Information

- The State of Data-breach Litigation and Enforcement: Before the 2013 Mega Breaches and Beyond

- United States V. Bazaarvoice: the Role of Customer Testimony In Clayton Act Merger Challenges

- The United States V. Bazaarvoice Merger Trial: a Panel Discussion Including Insights From Trial Counsel

THE UNITED STATES V. BAZAARVOICE MERGER TRIAL: A PANEL DISCUSSION INCLUDING INSIGHTS FROM TRIAL COUNSEL

Moderated by Karen Silverman1

I. INTRODUCTION

In the summer of 2012 Bazaarvoice, the leading provider of product ratings and review software and services, finalized the acquisition of its primary rival, PowerReviews. Two days later, the United States opened an investigation that led to a lawsuit in the Northern District of California to unwind the deal. In the fall of 2013, the parties squared off in court for a three week trial before Judge William H. Orrick, III. In January of 2014, Judge Orrick handed a victory to the government, issuing a 141 page opinion finding that the acquisition violated Section 7 of the Clayton Act.2

The case was watched by the antitrust bar and others for several reasons. First, merger challenges are only rarely litigated all the way through a trial on the merits. Also, the case marked the first time the Antitrust Division had returned to the Northern District for a merger matter since its ill-fated challenge to Oracle’s acquisition of PeopleSoft in 2004 in front of Judge Vaughn Walker.3 The somewhat unique posture of the case also generated interest. Because a Hart-Scott-Rodino filing was not required, the government was seeking to unravel an already consummated transaction, rather than trying to enjoin a merger from happening in the first place. And the case was of interest because it involved two relatively small technology companies, raising issues of the correct standard for judging a merger in a dynamic part of the economy.

A distinguished and knowledgeable panel discussed the case:

- Peter Huston was the lead trial counsel for the government. Mr. Huston is currently a partner with Sidley Austin LLP in its San Francisco office and a member of its Antitrust/Competition and White Collar: Government Litigation & Investigations practice groups. At the time of the trial, he was the Assistant Chief of the San Francisco office of the Antitrust Division where he handled both civil and criminal investigations and litigation.

- Boris Feldman was the co-lead trial counsel for defendant Bazaarvoice. Mr. Feldman is a litigation partner with Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich & Rosati in Palo Alto where he represents clients with securities, antitrust, M&A and corporate governance disputes and serves on the firm’s board of directors.

[Page 83]

- Arthur Burke is a litigation partner with Davis Polk working out of its New York and Menlo Park offices. He represents clients in a variety of antitrust, securities, corporate governance and general litigation matters. In his antitrust practice, he advises clients on the competition law aspects of mergers and acquisitions.

II. BACKGROUND

Many "eCommerce" companies that sell products online display customer ratings and reviews of their products. Ratings and review features on eCommerce websites allow prospective customers to see what others who have already used the product think about it. Reviewers rate the product, typically on a one to five scale, and supply a text review, often along with demographic information about themselves.

The ratings and review feature has become a ubiquitous part of online shopping. Consumers like to see authentic feedback from fellow consumers, and eCommerce companies have found that supplying this feedback is good for business in a number of ways. Having ratings and reviews on a website increases the likelihood that an internet search will direct a potential customer to the eCommerce website in the first place because of the way internet search algorithms work. It also has been shown that having ratings and reviews increases the likelihood that a visitor to a website will actually follow through and make a purchase. It also increases the likelihood that customers will be satisfied with their purchase, reducing the likelihood that the product will be returned.

[Page 84]

Product ratings and reviews can be found on the websites of product manufacturers as well as on the websites of eCommerce retailers and can be shared between manufacturers and retailers in order to increase exposure, a feature called "syndication."

Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews were the two leading suppliers of the software and services that collected, organized, moderated, displayed and syndicated ratings and reviews. Several other companies also provided ratings and review platforms and many eCommerce companies created the functionality in-house.

III. THE TRIAL AND THE COURT’S RULING

During trial, the government focused heavily on the companies’ pre-transaction documents. As emerging companies that may not have been as sophisticated as more established companies, the documents were candid and talked about the potential for raising prices after the transaction. They talked about the elimination of competition and used fairly purple language in doing so, which the DOJ capitalized on at trial.

[Page 85]

Bazaarvoice, on the other hand, relied on the market realities, primarily through the testimony of 107 customers, which they put in the record either through live testimony or depositions. Bazaarvoice called twelve customers live. The government only called two. The government was arguing that the customer testimony was overweighted, if not irrelevant to how the Court should assess the market and the competitive effects of the transaction.

[Page 86]

[Page 87]

In its ruling, the Court relied very heavily on the documents. The Court simply dismissed the customer testimony on the basis that the customers did not fully understand the markets in which they were purchasing services, which is an interesting proposition in markets with emerging companies. The Court dismissed post-merger evidence because it could be manipulated by the parties subsequent to the investigation.

The Court interestingly concluded that there were a few customers who might not be able to recover from this acquisition because they could not self-supply the reviews, but the Court did not really elaborate on how many of those customers there were or what percentage of the customer base they represented.

And then the Court fairly summarily concluded that entry was not easy, making it difficult to explore whether or not the Court’s entry analysis included the question of repositioning by several other players out in the market that obviously trade in reviews but were not central to the Court’s analysis.

After the Court issued its opinion, the parties negotiated a final judgment that included the divestiture of the PowerReviews assets to a third party, along with other remedies designed to insure that the buyer of those assets had a reasonable chance to replace the competition that had been lost. The stipulated final judgment eliminated the need for an appeal to the Ninth Circuit.

IV. DISCUSSION

Moderator: I first want to ask each of the panelists, starting with Peter, about the customer testimony question. I think that’s the one that sets up the most dramatic departure from previous practice. The DOJ’s position on the relevance of customer testimony in this case was in stark contrast to the position it took in the Oracle case and several earlier cases.

Huston: In the Oracle trial, the DOJ definitely placed a heavier emphasis on customer testimony than we did in this trial. In this trial, it was the defendant that emphasized the customer testimony. Judge Walker in the Oracle case was very dismissive of the customer testimony, and Judge Orrick for the Bazaarvoice case was somewhat dismissive. So, basically, two judges in the Northern District have expressed some objections to customer testimony in merger trials. After Judge Orrick issued his opinion, there was a fair amount of commentary about this. But I want to take a step back and just make sure we keep this all in context. When we at the Department of Justice investigate mergers, typically we will first get a Hart-Scott-Rodino filing, and if we think there is an issue that we need to look into, we will seek clearance from the FTC. Then, we often ask the parties for customer lists, and we start calling those customers. That’s the case despite the Oracle opinion and certainly despite the Bazaarvoice opinion. And that’s how it has to be. Our attorneys need to quickly get a handle on the market. Obviously, we can talk to the parties, but they are obviously biased in favor of the deal. To get a disinterested view, we need to talk to the customers. That’s going on as we speak. There are lawyers right now doing customer interviews back at the office. The customers will always be important in that context.

As for customer testimony at trial, I wanted to take a little bit of an issue with something that Karen said when she was presenting the background of the case, because Judge Orrick didn’t completely dismiss the customer testimony wholesale. In fact, he cites customer testimony throughout the opinion. I did a rough count, and found at least twenty

[Page 88]

five paragraphs of his opinion where he cites customer testimony to support his point, often corroborated by the parties’ documents. He cites the customer testimony for how these customers used ratings and reviews, the features that they like and what the sale cycles were like, which became important in the case. And most importantly, he relied on customer testimony for market definition purposes. Bazaarvoice, not surprisingly, was trying to expand the boundaries of the market to include lots of things like "social commerce" tools such as Facebook. And Judge Orrick actually looked to customer testimony to show that the customers did not view these social commerce tools in the same way that they viewed ratings and reviews. And "in-house" solutions, also known as "self-supply," or "do-it-yourself," which Karen mentioned, was a big part of the case as well. Judge Orrick relied on customer testimony to show why several customers couldn’t do it themselves, couldn’t supply this in-house. He also cited customer testimony to show the head-to-head competition between Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews.

So he didn’t reject customer testimony wholesale. He did, however, reject it when it came to the issue of the effect of the merger. Bazaarvoice was trying to show that these customers didn’t think there was going to be any anticompetitive effect. And they argued that that issue should rule the day. And there are several reasons why the Court rejected that sort of "effects" testimony from customers in favor of expert testimony. In large part it comes down to the different vantage point that a customer has from an economic expert. A handful of customers testified live, but most of the testimony from the 107 customers came in by deposition. It turns out if you really dig into their depositions, what you often saw was that these customers hadn’t paid very close attention to the merger. They hadn’t really paid much attention to what the effects of the merger were going to be. I have one example—this is slightly unfair because it is one out of many, but there was a deposition of a company called Astral Brands. And the question at the deposition was: "Do you believe that the merger of Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews has harmed your company?" We will lay aside, for the moment, that that’s probably the wrong question—this wasn’t a backwards looking damages case, we were trying to look forward and see what the effect was going to be going forward. But the answer was as follows:

THE WITNESS: I don’t really think of it in those terms. I don’t know. Harmed? I don’t know, I mean—I mean, I—probably not, but, I mean, I don’t know—like, has it harmed our company? I don’t—after the merger, I mean, nothing changed. Nothing—it wasn’t, you know—because, like I said, I didn’t know that they had merged until I was looking for a solution, another solution, and I was like: Oh, Power Reviews; and then: Oh, it’s Bazaarvoice now. I mean, no. No. I—we’ve managed to move forward, I guess.

Lots of these customers when they were put on the spot, with no preparation, shoved into a deposition and asked this question out of the blue—have you been harmed?—they kind of fumbled around, and it was clear they hadn’t really focused on the transaction or what its effects would be. The above example is a slightly extreme example, but that sort of answer was typical.

[Page 89]

Moderator: That’s a good segue into Boris. What did you guys do with that kind of response?

Feldman: First, it is a pleasure to be here today talking to you about a huge trial loss. You may think I am a little depressed here, but I am not, because tonight we are going to the World Series [displaying San Francisco Giants Rally Flag].

Huston: For the record, I, too, support the Giants.

Feldman: He supports them. He just thinks the government knows better than they do about baseball.

So what you just heard, I think, captures a disturbing attitude by the government. We are not going to have dueling customer quotes. I guess the reporter’s here, so I should say for the record that I think that Judge Orrick’s decision is second only to Justice Cardozo’s in Palsgraf and that there’s nothing that he didn’t get right in the decision. Now let’s go off the record. The government, their expert and the judge had an extremely paternalistic view of customers. So the customers weren’t all Astroglide or whatever you just said, the customers were some of the most sophisticated companies in America—retailers and brands—and virtually with unanimity they said, "We don’t care about this merger at all."

It is very easy for somebody on Pennsylvania Avenue to say, "Well, they don’t really know." When the government’s expert, lifetime professor/DOJ employee, was asked, "Who knows better about how this merger has affected the market, you or the customers?" He answered truthfully, "I do."

So to find citations in the opinion to customer testimony on things like, "Would you use Facebook instead?" is one thing, but the opinion gave very short shrift to the fact that the only fair reading of the customer testimony was they were not worried about this merger at all. They had lots of alternatives.

[Page 90]

If you ever want to go back and dive into the record, look at the testimony of B&H Photo. Raise your hand if you know B&H Photo. They are the best, most sophisticated camera company in the world and their online efforts are dazzling. And we had a Hasidic Jew come out, we had to get him back before Shabbat, and he was in charge of all their online efforts. I think anybody who had listened to him and really thought about his testimony would understand that this is such a small part of what they do, that if they want to move away or build it inside they can in a minute.

So this trial—actually, the entire case was very simple and two-dimensional. The government had the worst antitrust documents you may have ever seen, certainly since the 1930s, and the company had customers who virtually unanimously said, "This merger doesn’t hurt us. We don’t expect it to hurt us. It’s fine." And the documents won.

Moderator: That’s not an unusual setup, at least around here, where you have a small company that’s not really astute about the significance of its writings and a customer base that’s still evolving and enthusiastic going forward. Art, as a practitioner, how do you apply all these lessons in the real world?

Burke: I still advise clients, first and foremost, that customer reactions are critically important. So despite Oracle and despite Bazaarvoice, two cases which for different reasons didn’t seem to place a lot of importance on customer reactions, I certainly am not surprised to hear from Peter that it still is a critical component of the agency’s review, and that, frankly, if one is able to assuage customer concerns, in the vast majority of cases that is going to get your deal through and get it done more quickly. In the absence of vocal customer reactions, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission are usually, in my experience, going to allocate their resources in a different direction. They

[Page 91]

have a lot of deals to review, a lot of cases to litigate. And if they are picking where they are going to exercise their prosecutorial discretion, they are usually going to do that in a case where the people who are supposedly being harmed by the deal actually care about it and are vocal about it. Certainly in my experience customers are not shy about complaining.

Customers complain for all kinds of reasons, many of which don’t necessarily have a lot to do with antitrust, but they manage to sometimes dress up those complaints in antitrust terms in order to get better commercial leverage with merging parties. So despite the ruling here and despite the Oracle case, I think customer reactions are critical. And when advising clients, I tell them, aside from negotiating your deal, priority number one should be a customer communications plan, especially if the merging parties are competitors. I advise them to reach out to customers to find out who the squeaky wheels are, to try to get them comfortable so, again, there is not going to be that kind of problem down the road.

Now, in the absence of customer complaints, what made this attractive to the Division? I have to agree with Boris. It has to be the fact that there were just horrible documents, extraordinarily bad, and one might say that they reflect a candor on the part of the parties. The fact that more sophisticated companies, who have larger in-house legal departments and have regular training, manage not to use metaphors related to attack helicopters is not necessarily a reason that you should ignore that when a smaller company does use those metaphors. I can understand how the Judge and the Division might view those as being candid glimpses into the way the parties really do look at the business. The fact that larger companies may avoid that candor doesn’t mean you should disregard those documents, it just means larger companies are sometimes better at obfuscating their true intentions. Certainly the lesson learned here is to encourage mid-level companies to get training in place, and it really goes well beyond antitrust to just compliance culture generally. One would not generally want to encourage one’s employee to use military metaphors, attack gunships, etc., and there are good reasons far beyond antitrust for a compliance culture to try to get ahold of those kinds of documents and to educate employees not to think in that way. It is going to have collateral consequences, potentially not just for antitrust, but you can imagine all kinds of other compliance issues arise when people express themselves in that way.

My takeaway is, again, customers do still matter. Obviously it’s important for even small companies to worry about how people express themselves in emails and PowerPoints, etc.

[Page 92]

[Page 93]

Huston: What Art said makes my point to a certain extent. When he said, "get out there and get a communications plan for your customers because that’s important," it tells me, as an enforcer, that customers are often the last to know if two merging parties have anticompetitive ambitions. The customers are going to hear the rosy picture from the merging parties about why the merger is so great for them, and then they relay that to us as we go out and interview them. But the documents, which we’ve talked about (and this wasn’t a jury trial, so the fact that there were militaristic pictures, I don’t think swayed the judge necessarily) were important. The Court saw a long paper trail. These companies had been talking about merging for over a year, on again and off again. That paper trail from that process presented a very clear picture. It was coherent, it was consistent, it was corroborated, and it showed that these were really the only two games in town, Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews. They had been battling it out for a long time, and this battle was very annoying to Bazaarvoice. They were losing money because of it and decided, let’s just buy them and get rid of this nagging competitive problem that we have. So that’s what they did. Those pieces of evidence were far more reliable than the customer testimony, and that’s one reason the Court went that way.

Feldman: Much of what Peter said I would agree with. The trial’s over now. The case settled. There will be no appeal. I think a fair reading of the documents was that there were executives in the company that wanted to do the deal to eliminate competition, especially price competition, and the competition between the two was quite spirited.

One of the things Peter didn’t mention is the board never bought that. They wanted to do it for other reasons having to do with data analytics, which was the market the company was moving toward. But even if you accepted that they had lust in their heart, it is not an intent statute. Had it gone up on appeal, one of the issues would have been that it was a consummated merger with no indication of price impact. Is it enough just to say it’s over, and look at what’s happening in the market?

Just one other point. To say that there are only two players in town, well, those two players are rat testicles compared to Amazon. And to me the biggest surprise of the trial was in a deposition excerpt that the government put on when the person in charge of all this for Amazon.com was asked, "Do you ever consider making your ratings and review software, which is dominant, available for other parties to buy?" He said, "That’s something we look at every day." So Google, with all the things they do, and Amazon with all that they do, they don’t send out detail men to tech companies to sell their product review product today, but they could just snap their fingers and turn it on. It is just a switch, and once they flip it they obliterate everyone in the market.

Draw your own conclusion on how you advise clients. Here, you had a very strong case by the government of bad intent. You have players in the wings who dwarf the merging parties, for whom the merging parties are not even a rounding error, and customers who say they don’t care.

Huston: Your intent point is worthwhile. You’re right. It is not an intent statute and bad intent is not a formal element of a Section 7 violation. But from a trial perspective, as Tom Rosch, who mentored me and Karen and probably many others in this room, always said, you need to tell a story in any trial, including antitrust trials. Having the intent piece of the picture was important to tell that story. So that’s why we did what we did.

[Page 94]

Boris is right, Amazon was the creator of ratings and reviews. It wasn’t that long ago that Amazon was the only game in town. When they were just selling books, they decided to do this ratings and review thing. You could go online and figure out if a book was any good because you could see what real people said about the book, not just literary critics. It is true they are now a monster in the retail marketplace, no doubt about it, but as a retailer, they also are a competitor to Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews’ customers. So they could enter the market; whether they would get any traction or not is unclear. There certainly wasn’t any evidence that they were taking concrete steps to enter the market.

Moderator: So having put documents in context and customer testimony in context, the next obvious question is: How did you use your experts? You referred to the economists, Peter, and the opinion actually is quite expansive on the different views that the economists threw up on each side. So why don’t we go over to that topic.

Huston: I think the only thing I have to say about that for now is: If you find yourself in an antitrust case involving network effects, which ours did, hire Carl Shapiro and you’re probably going to do okay.

Moderator: What was Professor Shapiro able to do with the customer data and the revenue data?

Feldman: Ignore it. Nothing is better than that for me.

Huston: As Boris mentioned earlier, there was a point in the trial where the question was put to Professor Shapiro, "who knows better, you or the customers?" And he said, "I do." He acknowledged that, out of context, that might sound arrogant. But the Court obviously agreed. And the reason the Court agreed was because an expert is better situated to try and answer the ultimate question, which is: What’s going to happen in the future?

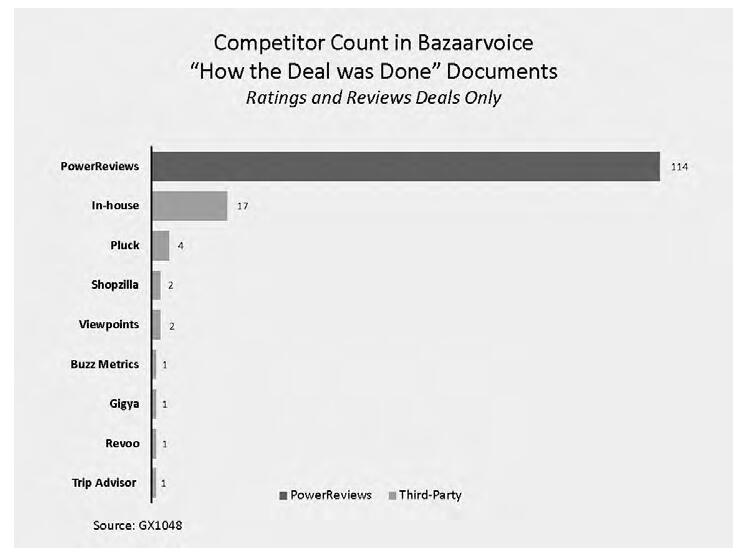

These merger cases are kind of weird because you’re trying to figure out what’s probable as far as what’s going to happen in the future. There are not very many other types of lawsuits where you really are trying to figure out what’s going to happen in the future based on what we have seen in the past. And experts are ideally situated to crunch the testimony, look at the data, look at the wins and losses. Bazaarvoice had these memos they would send out every time they won a deal, and they would try and say who they were up against, what the sales cycle was like. So he analyzed that data. He did his best to construct some market share information. There was no reliable, independent market share information out there, so he had to use a proxy, but he did that and came up with something that the Court could hang onto, and we were able to meet the Philadelphia National Bank presumption.

[Page 95]

Image description added by Fastcase.

Feldman: Professor Shapiro, a brilliant man, and he makes a great witness and I’d use him in a minute. I think there are some judges who would have looked at his testimony as junk science. You can always nitpick anybody. We found a lot of mistakes, not me, NERA, who we used as our experts (who we thought were superb, although Judge Orrick didn’t). If this case had gone up on appeal to the Ninth Circuit, depending on the panel, there might have been something said about these things that Professor Shapiro left out of his opinion and his willful ignorance that the customers made a difference, but in terms of courtroom performance, he’s just great.

I am maybe more of a cynic than Peter, who I think is pure. I say this as a compliment. You can get an expert to say pretty much anything. When the judge decides which way he wants to go, then he picks that expert to help fill out the opinion. If Judge Orrick had decided, notwithstanding the lust in their heart, the two together didn’t have any greater impact on the market, I think he could have easily gotten around Professor Shapiro’s opinion.

Burke: I am not quite as cynical as Boris, but I am sympathetic to his view. I think increasingly lawyers view their experts as hired gladiators where they go into the octagon together, to mix metaphors. And the fact is experts are good at this. If you pick the right one, they have done this many times, they know all the tricks, and if they are prepared properly, so often I feel like they cancel each other out. That isn’t to say there isn’t an occasional incident where a clever lawyer actually gets a gotcha question. After this, I have to go down to Silicon Valley to take an expert’s deposition. Hopefully that will be one of those instances.

[Page 96]

In most cases the experts succeed in protecting their opinion, in thinking through it in a way that is internally consistent so it is hard to find a chink in the armor. And in many respects they sort of cancel each other out. And ultimately the decider, whoever that is, whether it is in the case of a judge or a jury or in a case where you are arguing to an antitrust agency, there’s going to be enough information and substance from the economists they choose to support to justify their outcome. Which brings us back to why lawyers are important. The framing and presentation of the case by the lawyers have to be first and foremost. And the economists have to be in assistance and support of that. I am not suggesting that it happened here, I don’t think it did, but it is important to not let the economist run away with the case. The lawyers have to be the ones who are leading the advocacy.

Moderator: So we have now heard from Peter as to how the government put its story together and its reliance on a narrative that was compelling. Boris, do you want to elaborate on the counter narrative?

Feldman: Two things. You have all had cases where you’re dealt a bad hand with documents. One approach is to have the witnesses play stupid, and say, "I don’t know what that means." We did not take that approach in the depositions. The depositions here were as heartfelt as in any case. The government did a superb job. They deposed all the right people, and they had a lot of documents to use. Our view was you can’t run away from it, they have to say, "Yeah, that’s what I hoped. Yes, they really irritated me. Yes, I did think that the market was a duopoly at that point." But in the time since the merger, it is clear that other people have emerged, and we haven’t seen any kind of price-stabilizing effect from the merger.

So that was really the best we could do with the documents and hope that the judge finds the witnesses credible. I got the feeling he didn’t, really. That it was easy for him to say, "That’s what they wrote then and that’s what they say now, the only difference is the merger had been consummated."

In terms of all the customers, on one level it seems stupid that we deposed 107 customers. We would have done more, but the government kept going to court to try to prevent us from taking additional depositions. In a routine civil case you can often figure out who thinks they have a better case by who wants to slow it down and who wants to speed it up. If you have a plaintiff trying to slow the case down for trial, generally it is not that good a case. Here, when you have the government pushing all along to limit discovery, to restrict the number of depositions, to restrict the length of each deposition, that was a marker, for me, of what they thought—they had their documents and anything else could only detract from those. The way we picked the customers to depose was from a government response to an interrogatory which asked, "Which customers have you talked to in the course of your investigation?" Basically we said, "All right, we are going to depose everybody on that list."

And there were a couple that had grievances, they didn’t like the way this syndication was handled or they were mad at Bazaarvoice or PowerReviews about that, but our view was if we just pull a sample of ten or twenty, even if we have a nun do it in her habit, people will say that’s skewed and it is not ninety five percent statistical significance. So we took everybody the government identified as relevant and deposed them. We were under

[Page 97]

very strict time limitations at trial, or we would have had more witnesses. In the end, it didn’t overcome the documents.

Huston: I wish the executive depositions were as easy as Boris just made them sound, but in fact, rather than fighting the documents, they tried to obfuscate and talk about a lot of high-tech stuff that was off into the future. I don’t think they were lying necessarily, but they were talking about what they saw down the road and how they hoped to position themselves for the coming battle with Google that kept them up at night. But the reality was we were really fighting about the market they were currently in. So they were difficult, multi-day depositions of the executives, and it was tough to get straight answers out of them, and they were pretty slippery.

On the point about the customer depositions, both sides wanted to get to trial quickly. From the government’s perspective, we wanted to get to trial quickly because we thought this was an illegal transaction. Unlike the Hart-Scott-Rodino concept, where you can stop a deal before it happens, this had already happened. We didn’t want anticompetitive harm, or if there already was such harm we wanted to limit it. We wanted to get to trial quickly for that reason. I suspect the defendant wanted to get to trial quickly because it didn’t want this hanging over its head. So we settled on a fairly aggressive timetable and got the case to Judge Orrick. He moved heaven and earth, and rearranged his docket, but that didn’t leave a lot of time for discovery. And I remember—I think it was Boris, maybe his colleague, Jon Jacobson, saying—at the outset of the case saying, "Your Honor, we might need thirty depositions from customers." And I thought that seemed like a lot, but we were going to be okay with that. And then it turned out they shifted strategies, and it was 100. We were in fifty five different cities in twenty five different states doing depositions, triple and quadruple tracking in a compressed period of time.

Feldman: Once we started to take them, they were like Lay’s potato chips.

Moderator: One of the issues that Judge Walker had in the Oracle trial was the repetitiveness of the customer testimony; it was no longer probative or particularly additive after a point. So it is sort of an interesting strategic call. Why don’t you comment quickly, and then I want to turn it to the audience.

Burke: I want to pick up one thing that Peter said that provides a useful lesson here. It is not news to anybody, but I have no doubt that the executives at Bazaarvoice do worry all the time about large players that are adjacent to them or maybe even in their market, if you count Amazon. The possibility of Google entering this business, or Facebook, I am confident that that is true. It is so often the case that with the companies we advise—they are paid to look over their shoulder and to be worried about larger companies in adjacent spaces entering their business. And they often say to us, "How can this deal be a problem. Look at these other enormous giants that are just breathing down our necks." The simple truth is that it doesn’t work. It doesn’t work with the government, and it doesn’t usually work with courts either. That isn’t to say that it isn’t true or that it isn’t appropriate to present that. Part of a merger case is explaining the procompetitive rationale for the deal, why parties wanted to do it. So it is appropriate in that context to explain we are not doing this to eliminate competition, we are doing this to better compete with these larger companies that are near us. But I don’t think that usually works as a defense. It certainly doesn’t work with the government. As this case illustrates, it is a hard sell to the courts as

[Page 98]

well. So that’s another discontinuity that is an important point to explain to your clients. And it’s a difficult conversation to have. Because often you do get an incredulous reaction, but, fortunately or unfortunately, that is sort of the world we live in.

Feldman: Unlike a traditional merger case where you may be looking at a failing company, our clients tend to be future roadkill defendants. They say, "We are great today, but three months from now some punk in a garage can knock us out."

Moderator: It is very much about how dynamic our clients perceive the market to be, in contrast to the government, which is putting together a case, very often, based on a more static view of-—not just the market, but the harms, particularly in the case of a consummated merger.

Huston: Two points. So on the issue of what high-tech executives worry about, I will agree with the panel that they are often worried about, (A) who’s going to eat my lunch, and, (B) how can I get to that next big thing and make a lot of money? And high-tech executives, they don’t want to just open low margin restaurants that are highly competitive. They want to find a market where there’s a monopoly to be had. That’s where they can make some money. So they worry about those things, and there’s nothing wrong with that and you can credit that. By the same token, while they are worried about the next thing, they are still competing in the current thing, and that’s where the antitrust laws come in.

Moderator: Isn’t the question, though, whether the next thing is a competitive constraint on the current thing? The question I am asking is: Does DOJ credit the next thing when it can be demonstrated that it is a competitive constraint on whatever it’s currently staring at, at the moment?

Huston: The answer is certainly yes, and Carl Shapiro noted that in his report as well. And the judge also noted it in his opinion, basically saying we know what they are trying to do, but in the meantime it’s clear that they have an anticompetitive intent and there was an anticompetitive effect from the transaction. But if you can demonstrate in an entry analysis that there is someone that’s going to come in and change this and it’s credible, then the government will credit that. And if the government does it, I think the Court will, as long as there is good enough evidence.

Feldman: I don’t mean to interrupt, but there was no showing of anticompetitive effect. And when the professor was asked, "Did you do any research to show that there is?"—on day one of his testimony, he said, "Yes, and I found anticompetitive effect." And then when he slept on it and came back, he said, "No, I didn’t look into whether there was an anticompetitive effect." He thought there was potential for it in the future, but there was no showing in the record whatsoever of anticompetitive effect.

I am not an antitrust scholar, but one of you can probably write a doctoral dissertation on whether what Peter said about they all want to get a monopoly, whether in most technology areas that isn’t a good thing. If you look at most of the advances in technology from a user standpoint, there is generally a short period of near monopoly, not true monopoly, but total dominance of the market, and then they piss it away and somebody else knocks them out. So Instagram and Snapchat may be hot today, but the chance that you’re going to finance your child’s education by investing in them is low. Netscape for a period was just dominant, but it went away. So I understand that you don’t want just one railroad, or one soap manufacturer. But it may be that in emerging areas of technology, the way you make progress and sustain the necessary investments to do it is somebody is

[Page 99]

really good and they run up a huge market share and then somebody better comes along in a couple years.

Huston: More power to innovation and more power to people chasing the Holy Grail of monopoly profits, but when it comes to merging, we have different standards.

Moderator: That is just so ripe. Questions?

Audience member: How does a transaction like this get to the DOJ, where it is a very obscure corner of the market, it is an acquisition of a small company and doesn’t trigger any sort of filing and it appears that the customers are indifferent to the transaction and not really riled up?

Huston: Good question. As I mentioned before, a lot of our deals come to us by Hart-Scott-Rodino filing. This one didn’t because of the size of the parties threshold wasn’t met. However, one of our attorneys in Washington was reviewing a different deal that had a Hart-Scott-Rodino filing, and it happened to mention this rating and review space. And in that filing, it mentioned that the ratings and review space was a duopoly. Of course, that’s the kind of language antitrust lawyers are going to pick up a mile away, and that’s what he did.

And our lawyers also monitor the press. And this lawyer was reviewing TechCrunch, or one of the other media outlets that cover technology markets, and saw this deal announced and recalled that he had seen the market space described as a duopoly. He did some digging, and we were off to the races.

Moderator: But you set a land speed record for getting there, two days later, or something like that?

Huston: We are able to open up investigations very quickly.

Burke: It is a really interesting and tough problem for parties who have a deal that has an issue. I have had situations where parties have said, "We figured out that there’s some unusual reason the deal is actually not HSR-reportable." The value of this deal was $168 million. It was a standard purchase price, as I recall, but because of the weird way the HSR rules work, PowerReviews had so little revenue and assets, it wasn’t reportable. When companies find that out, they say, "That’s great. I don’t have to worry about HSR. Terrific news." Wait a second. You can still be sued afterwards.

And from a buyer’s perspective, then you are really in the worst position because the sellers are gone, they got their money. They are in the Bahamas now, and they can’t unwind that transaction. You can’t get that back. It is all on you as the buyer under that situation. There are situations I have been involved in where, despite the fact that the transaction was not reportable, we proactively notified the agencies and let them have a pass at it. That’s a hard decision to make. Honestly, in this transaction I would not have predicted that the agencies would have become aware of it any time soon. It is a very tough conversation to have with your client.

Moderator: Peter, were you in conversation with the companies before they closed? Did you ask them not to close?

[Page 100]

Huston: Not personally. I got brought in a little later than that. I know there was communication with the company after the deal was closed about preservation of the PowerReviews assets while the investigation proceeded, but Boris might know more about that.

Feldman: The problem was there was an Inspector Javert on the other side. That’s why God put him on this earth.

Moderator: Other questions?

Audience Member: When did the documents become known to the DOJ, was that after you opened your investigation or before?

Huston: After. Some documents were submitted voluntarily in response to our request and then CIDs were issued. Again, that happened before my time. When I came on the scene, my colleagues showed me some of these documents and I said, "Wow," and I said, "Find me some more." They kept coming and coming. And one of the issues we had at trial was that we had too much of this stuff. How do we prioritize and tell the story?

Feldman: You could describe it as antitrust porn.

Moderator: Obviously you didn’t think the threat of Google was realistic or that there was really anything out there that was going to curb their power in the future. What evidence would have been enough, and do you ever do a retrospective afterwards to figure out if you were right and that, in fact, there are players that enter the market?

Huston: My understanding is merger retrospectives are done at the agencies from time to time. I can tell you in this instance there were some pretty powerful barriers to entry. Now, Google is a huge company, and if it throws its weight into something, it is probably going to succeed, although it could be described as is a slightly fickle company. So it can enter and exit because it has the luxury of having so many resources. But as I mentioned earlier, this was a network effects business. Karen mentioned earlier this concept of syndication. Samsung will have reviews of its products on its site, and it will push them out to all the retailers because the more reviews you have, the better. So manufacturers like to have a lot of reviews. The retailers like to have a lot of reviews, they share reviews with each other so they can both get their content count up. Bazaarvoice and PowerReviews were expert at making that syndication work, and it created this network effect loop, and they kind of had a lock on that. So for someone to come in the market they would have to figure out a way to break that loop. And companies tried. There were companies who had entered the market and failed. There were others who entered the market from Europe and were having a very tough go of it. So we definitely looked at that.

[Page 101]

If there had been some credible evidence that an Amazon or a Google or another tech giant had a plan on the books, and it looked like it was something that could succeed, the government would have investigated that, but we just didn’t see that.

Moderator: Other questions? Since we’re making a record, go Giants! Thank you, everybody.

[Page 102]

——–

Notes:

1. Karen Silverman is a partner with Latham & Watkins LLP where she is a member of the firm’s Global Antitrust & Competition Practice Group, the Co-Chair of the firm’s Information Technology Industry Group and the managing partner of the firm’s San Francisco office.

2. 15 U.S.C. § 18; United States v. Bazaarvoice, Inc., No. 13-cv-00133-WHO, 2014 WL 203966, at *5 (N.D. Cal., Jan. 8, 2014).

3. United States v. Oracle Corp., 331 F. Supp. 2d 1098 (N.D. Cal. 2004).