Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Spring 2015, Vol. 24, No. 1

Content

- California Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law and Federal and State Procedural Law Developments

- Chair's Column

- Editor's Note

- How Viable Is the Prospect of Enforcement of Privacy Rights In the Age of Big Data? An Overview of Trends and Developments In Consumer Privacy Class Actions

- Keynote Address: a Conversation With the Honorable Kathryn Mickle Werdegar, Justice of the California Supreme Court

- Major League Baseball Is Exempt From the Antitrust Laws - Like It or Not: the "Unrealistic," "Inconsistent," and "Illogical" Antitrust Exemption For Baseball That Just Won't Go Away.

- Masthead

- Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide: In the Age of Big Data Is Data Security Possible and Can the Enforcement Agencies and Private Litigation Ensure Your Online Information Remains Safe and Private? a Roundtable

- Restoring Balance In the Test For Exclusionary Conduct

- St. Alphonsus Medical Center - Nampa, Inc., Et Al. and Federal Trade Commission, Et Al. V St. Luke's Health System, Ltd., and Saltzer Medical Group, P.a.: a Physicians' Practice Group Merger's Journey Through Salutary Health-related Goals, Irreparable Harm, Self-inflicted Wounds, and the Remedy of Divestiture

- The Baseball Exemption: An Anomaly Whose Time Has Run

- The Continuing Violations Doctrine: Limitation In Name Only, or a Resuscitation of the Clayton Act's Statute of Limitations?

- The Doctor Is In, But Your Medical Information Is Out Trends In California Privacy Cases Relating To Release of Medical Information

- The State of Data-breach Litigation and Enforcement: Before the 2013 Mega Breaches and Beyond

- The United States V. Bazaarvoice Merger Trial: a Panel Discussion Including Insights From Trial Counsel

- United States V. Bazaarvoice: the Role of Customer Testimony In Clayton Act Merger Challenges

- St. Alphonsus Medical Center-nampa and Ftc V St. Luke's Health System Ltd.: a Panel Discussion On This Big Stakes Trial

ST. ALPHONSUS MEDICAL CENTER-NAMPA AND FTC V ST. LUKE’S HEALTH SYSTEM LTD.: A PANEL DISCUSSION ON THIS BIG STAKES TRIAL

Moderated by Paul J. Riehle1

I. INTRODUCTION

The St. Luke’s2 case involved the 2012 acquisition by St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd. ("St. Luke’s") of Saltzer Medical Group ("Saltzer"). St. Luke’s is an integrated health system operating in Idaho and Oregon. Saltzer was an independent physicians’ association ("IPA") in Nampa, Idaho.

The St. Alphonsus entities3 and Treasure Valley Hospital ("TVH") first filed suit. The initial plaintiffs were joined by the Federal Trade Commission ("FTC") and the State of Idaho as plaintiffs.

There was no real dispute at trial that the product market was adult primary care services: plaintiffs claimed the product market was primary care services; and the defendants’ position was that the market was primary care physicians ("PCPs").

However, a big issue in the case was the definition of the geographic market. Below is a map of Idaho’s Treasure Valley.

[Page 110]

Boise is the largest city in Idaho with a population of 205,000. Nampa is the second-largest city in Idaho with a population of 85,000 and is about 20 miles from Boise.

Plaintiff St. Alphonsus runs hospitals in Boise and in Nampa. Plaintiff TVH is a physician-owned hospital in Boise.

Defendant St. Luke’s operates medical centers in Boise and Meridian, as well as medical centers in Nampa and clinics in all three cities. It does not have a hospital in Nampa or anywhere else in Canyon County. Defendant Saltzer was an IPA with the most physicians in Nampa.

Idaho District Court Judge B. Lynn Winmill agreed with plaintiffs that the geographic market was the city of Nampa. That finding caused the court to conclude that plaintiffs had made a prima facie case.

Pre-acquisition, St. Luke’s had eight doctors in Nampa, and Saltzer had 16 doctors in Nampa.4 The court found the affiliated entity post-acquisition would provide eighty percent of the primary care services to the market. The court’s findings of fact also, however, demonstrated that the transaction advanced Affordable Care Act policies:

- The intent by St. Luke’s and Saltzer was not anticompetitive, but rather to "improve patient outcomes" and the transaction would accomplish that objective.

- It promoted integrated, value-based healthcare that is a "consensus" solution to cost and quality concerns.

- It would "increase access to medical care" for the poor and uninsured.

After a four-week trial, fifty witnesses and 1,500 exhibits, Judge Winmill, held that the acquisition violated the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18, and the Idaho Competition Act, Idaho Code § 48-106, and ordered a divestiture as the remedy.

On February 10, 2015, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s judgment,5holding that the district court did not clearly err in determining that Nampa was the relevant geographic market, in its factual findings that the plaintiffs established a prima facie case that the merger will probably lead to anticompetitive effects in that market, and in concluding that the defendant did not rebut the plaintiffs’ prima facie case where the defendants did not demonstrate that efficiencies resulting from the merger would have a positive effect on competition. The Court of Appeals also held that the district court did not abuse its discretion in ordering divestiture. The defendants are considering filing a petition for rehearing and/or a petition for a writ of certiorari.

[Page 111]

Two distinguished and knowledgeable panelists discussed the case:

- Thomas Greene, special litigation counsel with the Bureau of Competition, Federal Trade Commission in San Francisco, served as lead trial lawyer for the FTC in the St. Luke’s case. Mr. Greene previously served in the California Attorney General’s Office as Chief Assistant Attorney General for the Public Rights Division and Chief of the Antitrust Law Section. He is a past chair of the Multistate Antitrust Task Force of the National Association of Attorneys General and a recipient of the association’s Marvin Award for national leadership. He is the former chair of the California Bar’s Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law Section, and is a recipient of the section’s Antitrust Lawyer of the Year Award.

- Jack R. Bierig was lead defense counsel for St. Luke’s Health System Ltd. in the St. Luke’s case. Mr. Bierig is a partner at Sidley Austin LLP in the firm’s Chicago office. Mr. Bierig has written and lectured widely on antitrust and health care regulatory topics. He teaches Health Law and Food and Drug Law courses at the University of Chicago Law School and the Harris School of Public Policy. He also founded the Center for Conflict Resolution.

- Paul Riehle, partner at Sedgwick LLP and chair of the firm’s Antitrust & Unfair Competition Practice Group, moderated this discussion. This discussion builds upon the recent panel discussion at the 2014 Golden State Institute by the Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law Section of the California State Bar. Mr. Riehle moderated the panel discussion with Messrs. Greene and Bierig.

Moderator: Judge Winmill found that the geographic market was Nampa. Boise is only twenty miles away from Nampa. One of the two non-governmental plaintiffs, St. Alphonsus, operated most of their hospitals in Boise. The other governmental plaintiff, TVH, is located only in Boise. Should Boise have been considered part of the geographic market?

Greene: I will start by putting this case in context. In the early 1990s, federal agencies, both the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, won a series of healthcare merger cases. However, starting circa 1995, nobody on the government side could win one of these cases. In Butterworth in 1996, the court took the view that if a nonprofit is the owner of a new, enlarged firm, that somehow that should take away the sting of increased concentration in the market.6 Sutter Health was another landmark case.7There, the court adopted an extraordinarily wide geographic area, one that basically stretched from Sacramento to Palo Alto. Within that very expanded space, there was no increased concentration to speak of.

Then there was a reassessment period, which I refer to that as the years in the desert. Between 2001 and 2008, the government brought no healthcare merger cases. Starting in 2008, there have been a series of government wins.

[Page 112]

Mixed Record of Government Enforcement Actions

• Rockford (1990)

• University Health (1991)

• Freeman (1995)

• Butterworth (1997)

• LIJMC(1997)

• Tenet (1999)

• Sutter Health (2001)

• Years in the Desert

• Evanston (2008)

• (nova (2008)

• OSF(2012)

• Reading (2012)

• Phoebe Putney (2013)

• St. Luke’s (2014)

• ProMedica (2014)

So the fair question here is: What happened?

First, the economics have become very helpful in trying to determine what a realistic geographic market is. There is a completely different way of thinking about the scope of the geographic market.

Second, there has been a significant rejection of the idea that nonprofits are dramatically different than for-profits. As Judge Posner said, human nature doesn’t change based on a corporate form.8

Third, all of the research since Butterworth has found that in concentrated markets, a nonprofit is pretty much the same as a for-profit in terms of real-world merger-specific efficiencies.

Finally, the court rejected the assertion that the Affordable Care Act protects otherwise anticompetitive mergers.

In Sutter Health, the court used the Elzinga-Hogarty test, a quantitative analysis developed in 1978. If ninety percent of a corporation’s sales are in a specific geographic market, that’s a strong geographic market; if it’s seventy-five percent, less strong, sort of on the bubble. It is based on a flow analysis that had its origin in a series of research papers that were done on coal markets. If you can bring a flatcar or a railroad car of coal into a market, you can probably bring ten or twenty railroad cars of coal into a market. It was

[Page 113]

really transportation costs that became the arbiter of whether the geographic market is wide or narrow. That is not the kind of market we have in healthcare, and that realization finally percolated through the economic analysis and the case law.

With respect to Sutter Health, this was one of the early moments in the years in the desert period. Tim Muris, Republican chair of the FTC said, in effect, "It is wrong we are losing the cases, it is wrong in the economics." One of the first things he did was order the FTC’s Bureau of Economics to do a retrospective analysis of what happened in Sutter Health.

The predictions in court were that competitors from outside the market would discipline the newly merged entity and the fact it was a nonprofit would also ameliorate any price effects that would flow from the merger. Wrong on both counts. There were dramatic increases in prices and no discipline from the firms that the defense economist said would constrain the merged hospitals. Quite simply the economics were bad. The conclusions of more recent studies have said just that.9

With that context, we turn to the St. Luke’s case and how we determined that Nampa is the market. The standard for geographic market is "where buyers can turn for alternate sources of supply?"10 So, the first question is: who are the buyers? In the healthcare context, the buyers are not consumers; they are insurers. There are two stages of competition. In the first stage, an insurer tries to set up a network, and it has an interest in having as broad a network as can be reasonably priced. The providers of care also want to be in the network because that’s a huge advantage to them. It is in that bargaining relationship between payer and provider that prices are set, and providers are either in or out of the network.11 From the plaintiffs’ perspective in St. Luke’s, this interplay defined the geographic scope of the market, as bargaining leverage depends on substitute physician groups in the market.

The way one sorts out whether someone can get by without a merged firm is to ask the question: What is the outside option? If one does not do business with this new, more robust, merged firm, can one offer an insurance product at a reasonable price that’s going to be salable without the merged firm?

[Page 114]

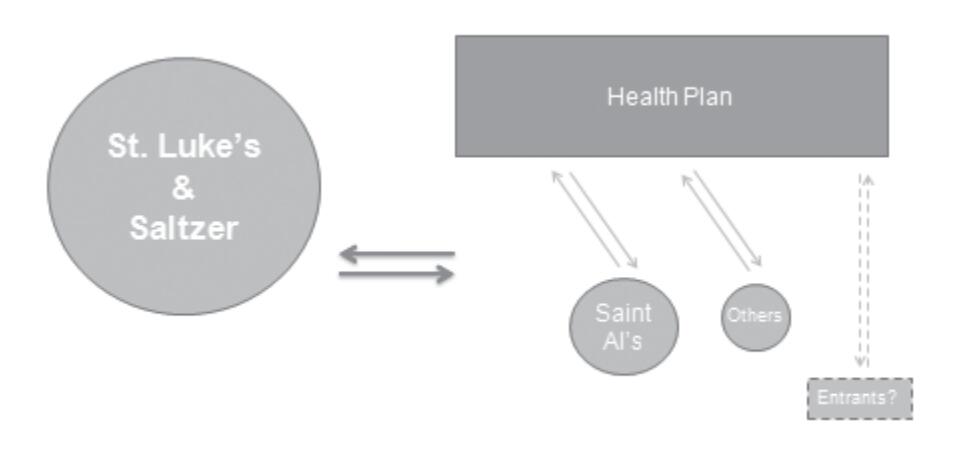

This slide represents the premerger world.

Image description added by Fastcase.

Saltzer is the practice group that was acquired by St. Luke’s. The medium-sized ball at the bottom left is the B-side company, Saltzer. St. Luke’s is up on the top left. Before the acquisition, Saltzer PCPs offer an attractive substitute for St. Luke’s PCPs, and vice versa. The health plan thus has a credible outside option when it negotiates with each provider.

This slide represents the post-merger world.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 115]

This shows that after the acquisition, a health plan loses a credible outside option and the provider gains negotiating leverage. Our economist used this slide to demonstrate that the outside option had essentially disappeared and given what was left, there was not much to create an alternate network with. Therefore, an increase in price could easily be extracted by this new, bulkier firm.

That is not the end of the story, of course. As trial lawyers, we don’t rely simply on Herfindahl indices and general statements about leverage. The payors gave us very good testimony that they cannot sell their product without local primary care physicians. Dr. Dranove, our economist testified that sixty-eight percent of Nampa residents get their care locally and that those who get care outside of Nampa at their place of work confirmed that patients like to get their care close to home.

We received testimony and documents from St. Luke’s that showed its executives thought Nampa was the appropriate geographic market. St. Luke’s also determined that it needed Saltzer primary care physicians in order to market itself to employers in Nampa. On the other hand, personnel from St. Luke’s clinic in West Boise, which was included in defendant’s market, testified that its clinic "never competed with providers in Nampa."

So everything taken together—ordinary course documents and testimony from the parties, payers and our economists—resulted in the conclusion that Nampa was the geographic market.

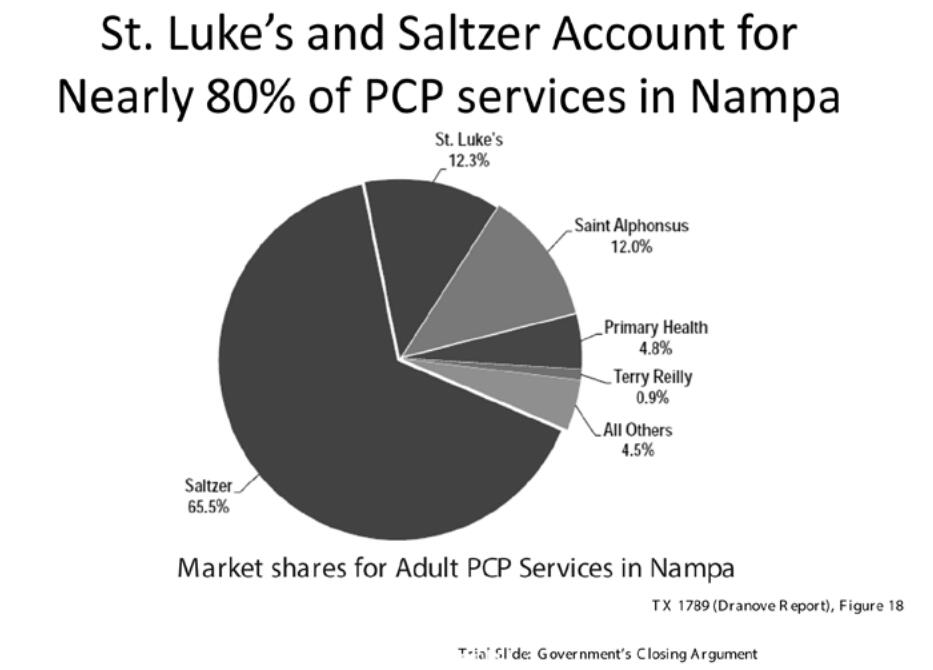

The result is this meatball chart.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 116]

The red is the new combined St. Luke’s-Saltzer, which is just a hair under eighty percent of the Nampa market. This generated HHIs which were very high, and the deltas were multiples of the deltas allowed under the Guidelines.12

Bierig: Rather than debate over the facts, I will focus on the analytical issues that emerge from this case. The first is the definition of the geographic market. Of course, in antitrust cases, the definition of the geographic market is the beginning of any analysis of competitive effect.

The government’s position in the case is that competition occurs only when providers compete in offering services to payors in order to be in-network. The government also stated many times in the case that insurance companies have to offer primary care physicians in every town in order to be competitive. Defendants think that there is a fundamental analytical flaw in the FTC’s position: Specifically, once in-network, providers still have to compete vigorously on the basis of price because payors can’t adjust co-payment levels and incentivize providers to choose preferred providers in a network. In other words, there is tremendous price competition among providers to get patients to choose their services. Indeed, the Court of Appeals, in FTC v. Freeman Hospital,13 found that the "decisive question" is how consumers would respond in the event of an anticompetitive price increase.

Here we don’t even have to deal with economic theory because we have a natural experiment. Prior to the affiliation, Saltzer was the dominant provider of primary care physician services in Nampa. Micron, which is an extremely large employer in Nampa, raised copayments in order to be treated by Saltzer physicians. Put another way, Micron made Saltzer an unpreferred provider. Interestingly enough, Saltzer patients left Nampa in droves and got care in Boise, Meridian, Caldwell and elsewhere. That indicates that Nampa is not a relevant geographic market.

Indeed, there’s an inconvenient truth here, to use our almost-President’s statement: As the court found, sixty-eight percent of Nampa residents currently receive adult primary care in Nampa. What that means is that nearly one-third of Nampa residents already receive adult primary care outside of Nampa—without any sort of anticompetitive price increase. The relevant question then is this: If there were a small but significant price increase, what would those sixty-eight percent of Nampa residents who currently receive adult primary care in Nampa do to get primary care? The fact is that most adults in Nampa work elsewhere, mostly in Meridian and Boise. This suggests that in the event of such an increase, a substantial number of people would seek adult primary care outside of Nampa as, in fact, they did when Micron raised copayment levels.

[Page 117]

In one of the cases that Tom refers to as the "desert period," the Court of Appeals in FTC v. Tenet Healthcare14 held that the fact that twenty-two percent of patients in the market posited by the FTC got care outside that market undermined the FTC’s proffered market. In our case, thirty-two percent of patients get care outside of the FTC’s market.

Here is further proof that Nampa is not a relevant geographic market. Saltzer, on the government’s own theory, had basically a monopoly of adult primary care physicians in Nampa prior to the affiliation with St. Luke’s. But Saltzer by itself, with basically one hundred percent of the market, never was able to raise fees above competitive levels. That certainly indicates that Nampa is not a relevant market, because if it were, Saltzer would have been able to raise fees above competitive levels. Notably, subsequent to the affiliation, prices in Nampa have not risen above competitive levels.

Moderator: Our next topic is: What must a plaintiff prove and what must the defense prove in a Section 7 case challenging the affiliation between a healthcare system and a defendant physician group?

Bierig: There are three separate analytical issues. Before we turn to them, I want to make two important points. One, there is a huge asymmetry in the FTC’s view between the burden on the plaintiff and the burden on the defendant. Two, the FTC’s view is fundamentally incorrect because it leads to condemnation of transactions that actually promote competition and that advance federal health policy as reflected in the Affordable Care Act.

The first analytical issue is what is the plaintiff’s burden to prove a prima facie case? Second, if the plaintiff does prove a prima facie case, what does the defendant have to show to overcome the presumption of illegality? Third, if the defendant makes the requisite showing, who bears the burden of proving that there is a less restrictive manner of achieving the benefits of the transaction?

As to the first of these three questions, here is what the FTC says. Plaintiffs establish a prima facie case of a Section 7 violation and a presumption of illegality by showing that the transaction will result in undue concentration in a relevant market. HHI analysis,15 in the FTC’s view, without more, makes out a prima facie case. Where an acquisition increases the HHI by 200 points, it is presumed likely to enhance market power and to be illegal.

The defense view is that the HHI analysis is just a starting point. That’s what the Court of Appeals, including two current Supreme Court Justices, said in United States v. Baker Hughes.16 To make out a prima facie case, a plaintiff must show a substantial likelihood of actual anticompetitive effects.

Federal Trade Commissioner Joshua Wright articulated this same position about a year ago when he said that the FTC should encourage courts to abandon the use of

[Page 118]

the structural presumption first in Philadelphia National Bank.17 He gave two reasons for this position. First, the structural presumption endorsed by Philadelphia National Bank doesn’t make economic sense. Commissioner Wright, who is an economist, points out that modern economic learning and empirical evidence do not support the notion that mergers that generate a post-merger firm with greater than thirty percent shares are systematically more likely to be anticompetitive. Second, this approach is far too sensitive to the market definition exercise.18 As we have just seen, it is an artificial exercise to decide whether the market is really Nampa or a larger market that includes Nampa and Boise and other towns.

So as Judge Posner observed in the HCA case, courts should no longer rely on a very strict merger decision like Philadelphia National Bank in the 1960s, but should really inquire into the probability of harm to consumers.19 That’s what the defense thinks.

If the defense is right, what do plaintiffs have to show? The FTC is of the view that the possibility of any price increase is enough. Our view is that there has to be a proof of likelihood of anticompetitive pricing.

I want to emphasize "anticompetitive pricing." Price increases always occur, but price increases standing alone do not create any concern under the antitrust laws. There are some additional questions that need to be raised. One is: To what extent are price rises following acquisitions in other geographic markets relevant?

The FTC pointed to various price increases in other markets outside of Treasure Valley. Doing so raises a number of issues. First, those increases didn’t demonstrate anticompetitive pricing. Prices always increase, but the relevant fact in other markets is very different from the market that is being analyzed.

A second question is this: To what extent is the presence of powerful purchasers a factor? In Boise, there were two or three insurance companies that dominated the market. They are not going to lie down and just accept anticompetitive pricing by providers. The presence of very strong buyers in a market must also factor into any analysis.

Another point. Boise is a very small community and the people on the board of St. Luke’s are the heads or significant executives of the large local employers who would have to bear any price increase. So the question is not, as the FTC suggests, whether St. Luke’s is nonprofit or not. Rather, the issue is whether the fact that the hospital board is comprised of business leaders whose companies will bear higher prices will affect the likelihood of a price increase.

[Page 119]

Now, assuming that the plaintiff makes out a prima facie case, what does the defendant have to show in rebuttal? Here’s the FTC’s view: To rebut the "strong presumption of illegality," defendants must show that their claimed efficiencies are not only "extraordinary" but also "substantiated, verifiable and merger-specific."20 Indeed, "Defendants must verify by reasonable means the likelihood and magnitude of each asserted efficiency, how and when each would be achieved (and any cost of doing so), and how each would enhance the merged firm’s ability and incentive to compete and why each would be merger-specific."21 No one can meet that test.

The correct test is whether there is a reasonable likelihood that substantial pro-competitive benefits will take place over time. The District Court for the District of Columbia said it quite well: There is "a difference between efficiencies which are merely speculative and those which are based on a prediction backed by sound business judgment."22 Or as the District of Columbia Court of Appeals said, a defendant cannot be required to produce evidence of pro-competitive benefits with "a degree of clairvoyance alien to Section 7."23

Here, there are several benefits from this transaction. It resulted in the treatment of all patients, regardless of ability to pay. It increased community outreach programs. And, probably most importantly, the transaction helped St. Luke’s move toward being a fully-integrated clinic system and to facilitate the transition from fee-for-service to risk-based delivery of care. Those are very important pro-consumer benefits.

The question arises: How specific and demonstrable does that proof have to be? The defense view is that it does not have to be all that specific because the effects of a transaction cannot be measured at the time of the case. It is going to take a while for these effects to be seen. To require someone to have to prove, with the kind of specificity that the FTC is talking about, all these benefits is basically to say that a defendant can never win. However, the Ninth Circuit, although not in an antitrust case, but a case with some analogies, cautioned against undoing a healthcare merger where doing so might detract from the quality of care for patients and would mean that innovative procedures made possible by the transaction would have to be abandoned.24

This is a very important question that has never been answered, because most of the Section 7 cases are strictly horizontal cases in which two hospitals merge, and there are not a lot of pro-consumer benefits that arise from horizontal mergers. This is more of a vertical situation in which a physician group is affiliating with a hospital system, and there are very significant pro-consumer benefits that arise.

[Page 120]

The final question on the burden issue is this: Who bears the burden of showing that the pro-competitive benefits could reasonably have been achieved in a manner less restrictive of competition? The FTC’s position is that the defendant has the burden on the question of less restrictive alternatives. There is no law in Section 7 cases. Even in Section 1 cases, there are not too many cases that have gone this far, and so there is not a lot of law. The law that exists suggests in the Section 1 context that the burden reverts to the plaintiff on this issue. The leading case is the Clorox case in the Second Circuit.25 There are two cases from the Ninth Circuit, Hairston26 and Bahn,27 in which the Ninth Circuit, albeit not with very thorough discussion, said that if the defendant rebuts the plaintiff’s prima facie case, the burden goes back to the plaintiff to prove that there were ways less restrictive of competition to effectuate the transaction.

The problem with the FTC’s position analytically, conceptually and from a policy point of view, is that a hospital system can never integrate through employment of physicians whose practices it acquires. That is because a joint venture offers, at least in theory, an alternative, less restrictive way of competition. In fact, there is no consensus on whether employment of physicians is as effective at achieving efficiency as joint ventures are. In my view, at least, the antitrust law should not result in favoring one legitimate structure over another.

This brings me to a very important and interesting conceptual issue in antitrust enforcement: What is the role of judicial restraint in Section 7 cases? On that, the Ninth Circuit in United States v. Syufy observed. "[A] court ought to exercise extreme caution because judicial intervention in a competitive situation can itself upset the balance of market forces, bringing about the very ills the antitrust laws were meant to prevent."28

Judge Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit made the same point in a law review article: "If the court errs by condemning a beneficial practice, the benefits may be lost for good."29 Put another way, a judgment erroneously prohibiting behavior with real pro-competitive potential will create significant and long term social costs.

The defense believes the St. Luke’s trial court decision that this case is anti-patient and anti-consumer and that the intervention of the court is bringing about the very sort of anti-consumer result that the antitrust laws, as a consumer protection measures, were meant to prevent.

Greene: I will begin by briefly talking about efficiencies, because there are major differences in our perspective in terms of the case law and structure of the analysis.

The notion that there is little or no case law on where the burden lies and what it is, is incorrect. In H&R Block,30 discussed at last year’s Golden State Institute, the court

[Page 121]

ruled that the hurdle for demonstrating efficiency claims is high.31 First, they have to be merger-specific. If the same benefits using a different strategy, a less anticompetitive strategy, is possible, then the efficiencies do not count. That is the essence of this idea of merger specificity. Secondly, the efficiencies have to be reasonably verifiable. A defendant cannot simply say, we are going to put on a show, and you will like it when you see it.

Here, St. Luke’s failed to show that it needed to employ physicians in order to achieve the proposed gains. That was a conclusion of the court which was generated from a variety of sources. One was expert testimony. Plaintiffs’ expert Dr. Kenneth Kizer, who now teaches at the University of California, Davis Medical School and was formerly the chief of health services for the Veterans Administration in the 1990s when he turned that system around, cited a number of other systems in which non-employment relationships—non-exclusive relationships—could generate the kinds of efficiencies that were being claimed for the St. Luke’s transaction.

There were also problems with the defendants’ evidence. Their expert said, in effect, "Well, I am not sure they’ll be able to pull this off. In ten years we’ll know. We just can’t tell now." The head of clinical efficiencies, a physician, said, "I’m not sure we’re going to get there in five to ten years, but we’re trying."

Moreover, this was the last in a series of transactions, roughly twenty transactions in eighteen months, in which St. Luke’s purchased practice groups. Plaintiffs’ economist went back and looked at all those transactions, and the result, based on that econometric analysis, is that in most of those transactions, prices actually went up, cost did not go down, and in the others it was basically neutral.

When all of those pieces of evidence were put together, there was not much of a case here in terms of either merger specificity or verifiable improvements in quality or efficiency.

There were specific claims that only by way of this transaction could the B-side firm, which already had an electronic medical record system, be able to access the positive benefits of St. Luke’s electronic medical records system. It turned out that St. Luke’s was going to offer the Epic system, which they had just purchased, to every independent physician in Idaho, which meant that this was not a merger-specific benefit.

In advising clients, it is very important to have a sense that there is, in fact, a great deal of case authority out there. In Rockford, for example, the court evaluated a variety of frequently made claims, including improved standardization of care. The court there said no, that’s not a merger-specific benefit. There are a variety of ways to do that and it does not offset the obvious anticompetitive implications of an eighty percent market share.32

Another interesting case is OSF Healthcare.33 The court there ruled that claims are not enough. Failure to address cultural, financial, regulatory and other practical obstacles

[Page 122]

rendered the claims speculative.34 Thus, it is not enough to say that a transaction will standardize care or cut costs or facilitate risk-based contracting. The defense has to be able to show how specifically the claimed result will flow from the deal. Simply, how do we practically get from here to that better place? The questions of what are the hurdles and how are they to be addressed have to be considered carefully in order for the claimed efficiencies to be counted.

On the question of burden, this is not a new world. The burden has been on the defense for a long time, and articulated in a variety of cases. Heinz holds that there must be rigorous analysis and the court has to be sure that the claims are more than speculation and promises.35 The courts, Areeda and Hovenkamp, and others state that the burden on the defense is somewhere between extraordinary and enormous.36 The idea is that once you show that there is a presumptively unlawful merger, the defense then has to show that the efficiencies will dramatically outweigh any anticompetitive problems. It is not a balancing test.

From a jurisprudential perspective, there are two rationales for this burden-shifting regimen. The first is that efficiencies are a defense and defendants bear the burden of any defense. The second, made by Areeda and Hovenkamp, is that those with the most knowledge should bear the burden of persuasion. In a merger, those who know best about efficiencies are the two companies that are merging. Presumably, in a pro-competitive merger, future efficiencies should be a big reason for the transaction. Thus, there should be ordinary course of business plans and specific things in the record that support the idea that there will be efficiencies.37

Finally, one of the most interesting aspects of this from my perspective is the economics. As I can tell you as someone involved in the Sutter/Summit matter, the economic analysis during that period was just terrible for plaintiffs. That world has changed very dramatically.

The most recent studies, at the time that we tried St. Luke’s, economic analysis depicted no compelling benefit from employing physicians. But more recent studies find that somewhat looser relationships than employee and employer relationships result in better and cheaper care. Moreover, these studies demonstrate that the tightest

[Page 123]

relationships—like those advocated by St. Luke’s—result in higher prices but with little or no improvement in quality.38

Moderator: What is the proper role of healthcare policy, specifically the Affordable Care Act, in evaluating the propriety of a transaction?

Greene: We showed versions of this slide in both opening and closing.

The Affordable Care Act is built upon a set of foundational ideas, the most important of which is that competition should be a major arbiter and major driver of healthcare outcomes in the United States. The Act is built upon the idea of competition. When you look at the Act’s DNA, one should not be surprised that the ACA specifically says that

[Page 124]

nothing in the Act "shall be construed to modify, impair, or supersede the operation of any of the antitrust laws."39

When one looks at the fundamental policy underpinnings of the Affordable Care Act and its statutory text, competition is the order of the day. That’s the world that we want to protect at the federal level, both from an ACA perspective and the federal antitrust law perspective.

Implementing regulations for the creation of accountable care organizations ("ACOs") make clear that facilitating creation of ACOs is not an excuse for anticompetitive mergers. The implementing regulations provide a structure for notifying federal antitrust agencies of ACOs that may be an antitrust problem. So essentially there is a partnership between CMS and the antitrust agencies to address potentially anticompetitive mergers under the ACA. The law here is quite clear that the ACA does not support the idea that it is a free pass to do anticompetitive mergers in healthcare.

The other aspect of this, which is a bit more subtle, is the argument that financial integration and clinical integration are the same, specifically the idea that the more financially integrated doctors and the hospital are, the more clinical integration is achieved. But that is not so. It turns out that less restrictive financial integration can lead to better clinical integration and lower costs.40 Simply put, financial integration does not necessarily lead to clinical integration.

Bierig: On this topic, I am reminded, of what Elizabeth Taylor’s seventh husband said to her on their wedding day, "Don’t worry, I’ll be brief."

The defense in St. Luke’s agrees on some of the views just articulated regarding the Affordable Care Act. But the real question is this: To what extent do healthcare considerations factor into the evaluation of efficiencies that arise from a transaction? To argue that healthcare considerations do not factor into that is really to ignore precedent.

In a Section 2 case 20 years ago, the Seventh Circuit said in Marshfield Clinic: "We live in an age of technology and specialization in medical services. Physician practices in groups, in alliances, in networks, utilizing expensive equipment and support. Twelve physicians competing in a county would be competing to provide horse-and-buggy medicine. Only as part of a large and sophisticated medical enterprise such as the Marshfield Clinic can they practice medicine in rural Wisconsin."41

[Page 125]

The analysis in Marshfield Clinic has tremendous relevance to the St. Luke’s case because the Saltzer physicians were a small group of primary care and other related physicians in Nampa, Idaho. Through integration into the St. Luke’s system, they were able to practice twenty-first century medicine by having much greater access to more robust electronic medical records and all sorts of data analytics; by being part of developing practice guidelines; and by being free from the economic constraints imposed by independent practice, which limits the number of no-pay and low-pay patients that a physician can see. So to say that healthcare policy doesn’t enter into it is blink reality.

Similarly, in Tenet Health Care the Eighth Circuit found the fact that a transaction will lead to integrated delivery of care and ultimately, to better medical care is a relevant factor in antitrust analysis. Evidence that a transaction will lead to "integrated delivery" of care and ultimately "better medical care" is relevant.42

If you look at the findings of Judge Winmill in St. Luke’s, you will see that all the benefits that he found from this case are the exact goals of the Affordable Care Act. To say that those factors have no place in antitrust analysis after Congress has sought to achieve them is a very narrow and wrong view of the antitrust laws.

Moderator: Judge Winmill ordered divestiture, which has been stayed pending appeal. Is divestiture the proper remedy?

Bierig: The answer is no. Here’s the FTC’s position: divestiture is the presumed remedy in Section 7 cases brought by the government. I don’t fundamentally disagree that divestiture needs to be thought about as a remedy in any Section 7 case. But at the same time, divestiture should not be ordered without substantial evidence that the benefit outweighs the harm.

All these cases cited by the FTC about the propriety of divestiture arise in the case of purely horizontal mergers between two banks or hospitals, where there are none of the benefits that we see in this case. So the question from an antitrust policy issue is this: What factors overcome the presumption of in favor of divestiture? Here, there are two.

First, divestiture should not be ordered for a transaction in which substantial consumer benefits would be lost by the divestiture.43 Second, divestiture should not be ordered where divestiture will not re-inject competition into the market. The purpose of divestiture is to put back into the market the competition that was supposedly lost as a result of the transaction.

Both of these factors are present here. As discussed already at length, there are clearly pro-consumer benefits that arise from this transaction. The court so found. The question that the court ought to be asking itself is this: Assuming that the transaction is unlawful, can we structure a remedy that will preserve these pro-

[Page 126]

consumer benefits and at the same time address the concern about anticompetitive pricing that the plaintiffs voiced?

Also, in this case, when the affiliation with St. Luke’s was announced, Saltzer’s seven highest earners, most of the surgeons, left and went elsewhere. That result was economically devastating for Saltzer, which has been hemorrhaging money as a result. It is quite clear, even though the government won’t acknowledge it, that in the event of divesture, Saltzer will not survive as a competitive entity. Doctors will splinter off, retire or move elsewhere. Others will be picked off by St. Luke’s or its real rival, which is St. Alphonsus. To the extent that the purpose of divestiture is to re-inject competition into a market, divestiture ought not to be ordered where it is quite clear that divestiture will not have that effect.

The defense believes that the Ninth Circuit should think seriously about whether divestiture should be not only the presumed remedy, but the inevitable remedy. In this case, it would be entirely the wrong remedy.

Greene: A couple of factual points here. The B-side firm was an extremely profitable firm. It was the last large independent practice group in the state of Idaho. It was doing just fine before it did this transaction. What they did lose, or what they will lose if they don’t have the opportunity to affiliate with St. Luke’s, is a thirty percent increase in pay—that was part of the transaction. Plaintiffs thought that was at least, in part, due to the increased market power associated with the deal.

With respect to the surgeons, they were essentially driven out by St. Luke’s and the folks that were in favor of the deal within the Saltzer Medical Group. So that was, from plaintiffs’ perspective, a self-inflicted wound. That was also the view the court took, that this was not something that was appropriate for consideration.

Finally, in the deal documents, Saltzer and St. Luke’s went through an elaborate process that discussed what would happen if the court ordered divestiture. Among other things, Saltzer gets to keep $11 million in the event they are ordered to divest.

There were a lot of factors here that are factual and important to the court as it considered its order. In terms of case authority, in American Stores., the Supreme Court ruled that divestiture is the "most suitable remedy in a suit for relief from a § 7 violation."44 A number of cases say that. For example, the Ninth Circuit long ago said that divestiture "should always be in the forefront of a court’s mind when a violation of § 7 has been found."45

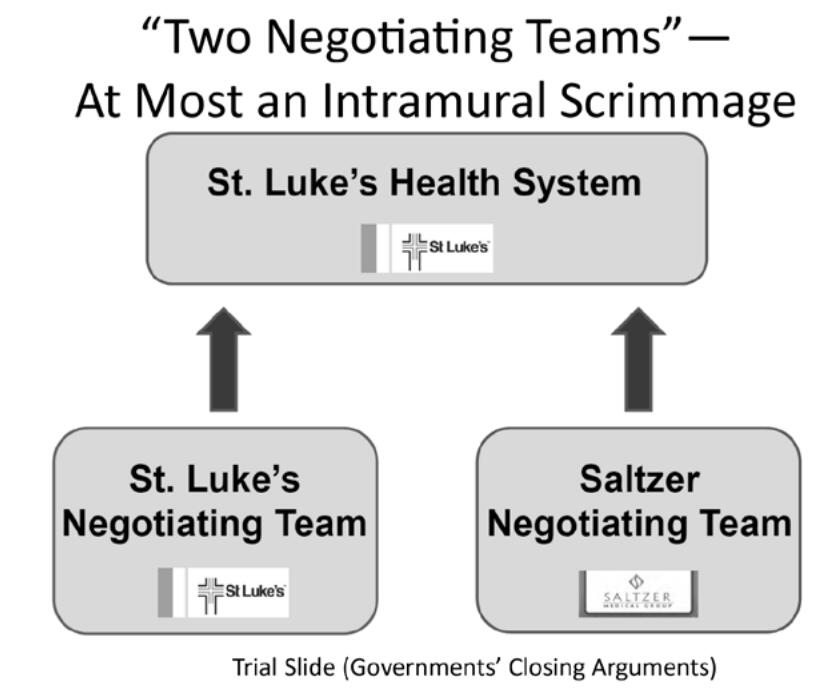

The remedy defendants proposed was separate negotiating teams, one for Saltzer and one for St. Luke’s. In the Evanston case, the FTC agreed to this sort of remedy in a retrospective merger challenge that took place seven years after the transaction.46 The problem was the remedy was not used at all. Such remedies do not work and

[Page 127]

would require extensive monitoring of literally thousands of services and prices associated with each of those services. From a public agency perspective, anything like this requires huge amounts of monitoring, is unworkable and is too easy to evade.

This is a slide that we used during closing arguments.

Image description added by Fastcase.

The proposed two negotiating teams is no more than an intramural scrimmage. In fact, looking at the economics of this kind of proposal, if a patient did not go to Saltzer, where else would the patient go; typically, consumers in this particular market would go to the other provider.47 So once they merged, if Saltzer prices went up, then St. Luke’s would capture that business, and the reverse would also be true. From an economic theory perspective, what I just suggested is what a group of academic economists just shared with the Ninth Circuit in an amicus brief.48

The defendants proposed remedy does not work. At the end of the day, divestiture is the right remedy.

[Page 128]

——–

Notes:

1. Paul Riehle is a partner at Sedgwick LLP in the San Francisco office, chairs the firm’s Antitrust & Unfair Competition Practice Group, co-chairs its Class Action Practice Group and is a member of its Healthcare Task force. Mr. Riehle has been a member of the Executive Committee of the California State Bar’s Antitrust & Unfair Competition Law Section since 2010. He currently serves as the Section’s vice-chair for the Golden State Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law Institute.

2. Saint Alphonsus Medical Center-Nampa, Inc. v. St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd., Nos. 1:12—CV—00560—BLW, 1:13-CV-00116-BLW, 2014 WL 407446 (D. Idaho Jan. 24, 2014).

3. The entities are Saint Alphonsus Medical Group-Nampa Inc., Saint Alphonsus Heath System Inc., and Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center, Inc.

4. Notably, these numbers meant that the acquisition did not come close to meeting the Hart-Scott-Rodino merger reporting requirements.

5. Saint Alphonsus Med. Ctr. v. St. Luke’s Health Sys., No. 14-35173, slip op., 2015 WL 525540 (9th Cir. Feb. 10, 2015).

6. Federal Trade Commission v. Butterworth Health Corp., 946 F.Supp. 1285, 1296-97 (W.D. Mich. 1996).

7. California v. Sutter Health Sys., 130 F. Supp. 2d 1109 (N.D. Cal. 2001).

8. Hospital Corporation of America v. FTC, 807 F.2d 1381, 1390 (7th Cir. 1986).

9. See, e.g., Steven Tenn, The Price Effects of Mergers: A Case Study of the Sutter-Summit Transaction (FTC Working Paper No. 293, 2008) (explaining that distant competitors did not constrain prices and neither did non-profit status of health system); see also H.E. Frech et al., Elzinga-Hogarty Tests and Alternative Approaches for Market Share Calculations in Hospital Markets, 71 Antitrust L.J. 921 (2004) (discussing the theoretical weaknesses of Elzinga-Hogarty tests).

10. The standard for geographic market is "where buyers can turn for alternate sources of supply." Morgan, Strand, Wheeler & Biggs v. Radiology, Ltd., 924 F.2d 1484, 1490 (9th Cir. 1991).

11. "[T]he vast majority of health care consumers are not direct purchasers of health care—the consumers purchase health insurance and the insurance companies negotiate directly with the providers." Saint Alphonsus Medical Center-Nampa, Inc. v. St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd., Nos. 1:12-CV-00560-BLW, 1:13-CV-00116-BLW, 2014 WL 407446, at *6 (D. Idaho Jan. 24, 2014) (emphasis added).

12. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index ("HHI") is calculated by summing the squares of the market shares of all participants in the market. A market is considered highly concentrated if the HHI is above 2,500, and a merger that increases the HHI by more than 200 points is presumed to be likely to enhance market power. See U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines § 5.3 (2010), available at http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/guidelines/hmg-2010.html.

13. FTC v. Freeman Hospital, 69 F.3d 260, 269 (8th Cir. 1995).

14. FTC v. Tenet Health Care Corp., 186 F.3d 1045 (8th Cir. 1999).

15. See supra note 12.

16. United States v. Baker Hughes, Inc., 908 F.2d 981, 991-92 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (holding that plaintiff must show a substantial likelihood of actual anticompetitive effects to make out a prima facie case).

17. United States v. Philadelphia Nat’l. Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 363 (1963) (holding that plaintiffs establish a prima facie case of a Section 7 violation, and a presumption of illegality, by showing that the transaction will result in undue concentration in a relevant market).

18. Joshua D. Wright, Commissioner, FTC, "The FTC’s Role in Shaping Antitrust Doctrine: Recent Successes and Future Targets" (Sept. 24, 2013), available at http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_statements/ftc%E2%80%99s-role-shaping-antitrust-doctrine-recent-successes-and-future-targets/130924globalantitrustsymposium.pdf.

19. Hospital Corp. of America v. FTC, 807 F.2d 1381, 1386 (7th Cir. 1986) (stating that courts should no longer "rest, on the very strict merger decisions of the 1960’s," but instead "inquire into the probability of harm to consumers").

20. Plaintiffs’ Joint Pre-Trial Memorandum at 19, Saint Alphonsus Medical Center-Nampa, Inc. v. St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd., Nos. 1:12-CV-00560-BLW, 1:13-CV-00116-BLW (D. Idaho Sept. 10, 2013).

21. Id. (citing U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines (2010)).

22. FTC v. Staples, Inc., 970 F. Supp. 1066, 1089 (D.D.C. 1997).

23. United States v. Baker Hughes, Inc., 908 F.2d 981, 987 (D.C. Cir. 1990).

24. Miller v. Cal. Pac. Med. Ctr., 991 F.2d 536, 545 (9th Cir. 1993).

25. Clorox Co. v. Sterling Winthrop Inc., 117 F.3d 50, 56 (2d Cir. 1997).

26. Hairston v. Pacific 10 Conference, 101 F.3d 1315, 1318-19 (9th Cir. 1996).

27. Bahn v. NME Hospitals. Inc., 929 F.2d 1404, 1413 (9th Cir. 1991).

28. United States v. Syufy Enters., 903 F.2d 659, 663 (9th Cir. 1990).

29. Frank H. Easterbrook, The Limits of Antitrust, 63 Texas L. Rev. 1, 2-3 (1984).

30. United States. v. H & R Block, Inc., 833 F. Supp. 2d 36 (D.D.C. 2011).

31. Id. at 89.

32. United States. v. Rockford Mem’l Corp., 717 F. Supp. 1251, 1291 (N.D. Ill. 1989) aff’d 898 F.2d 1278 (7th Cir. 1990).

33. FTC v. OSF Healthcare System, 852 F. Supp. 2d 1069 (N.D. Ill. 2012).

34. Id. at 1093-94.

35. FTC v. Heinz Co., 246 F.3d 708, 721-22 (D.C. Cir. 2001) ("[T]he the court must undertake a rigorous analysis of the kinds of efficiencies being urged by the parties in order to ensure that those ‘efficiencies’ represent more than mere speculation and promises about post-merger behavior."). "[T]he high market concentration levels present in this case require, in rebuttal, proof of extraordinary efficiencies." Id. at 720 (emphasis added).

36. Areeda & Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law ¶ 976d.3 (2014) (Presumptive Rules for Efficiency Claims).

37. Id.

38. Brief for Amicus Curiae Center for Payment Reform in Support of Plaintiff/Appellee Federal Trade Commission and Affirmance of District Court’s Order, Saint Alphonsus Medical Center-Nampa Inc., St. Luke’s Health Sys., Ltd., No. 14-35173 (9th Cir. Aug. 20, 2014); see also Baker, et al., Vertical Integration: Hospital Ownership is Associated with Higher Prices and Spending, 33 Health Affairs 756, 762 (May 2014) ("Our study has two key findings. First, in its tightest form, vertical integration appears to lead to statistically and economically significant increases in hospital prices and spending. This is consistent with the hypothesis that vertical integration increases hospitals’ market power. . . Second, the consequences of looser forms of vertical integration were more benign and potentially socially beneficial. Increases in these forms of integration did not appear to increase prices or spending significantly and may even decrease hospital admissions."); Kralewski et al., Do Integrated Health Care Systems Provide Lower-Cost, Higher-Quality Care?, Physician Exec. J. 14, 18 (March-April 2014) ("[O]"ur data suggest that these large complex structures might increase costs with no gains in quality.").

39. 42 U.S.C. § 18118(a).

40. See, e.g., Thomas C. Tsai & Ashish K. Jha, Hospital Consolidation, Competition, and Quality: Is Bigger Necessarily Better?, 312 J. American Med. Assoc. 29, 30 (July 2, 2014) ("Many small health care organizations are excellent, proving that size is no prerequisite for delivery of high-quality care. Higher health care cost from decreased competition should not be the price society has to pay to receive high-quality care."); Abe Dunn & Adam Hale Shapiro, Do Physicians Possess Market Power?, 57 J. L. & Econ. 159, 186 (2014) (finding that physicians in concentrated markets are able to exercise market power); Alison Evans Cuellar & Paul J. Gertler, Strategic Integration of Hospitals and Physicians, 25 J. of Health Econ. 1 (2005) ("[Hospital-physician] integration "has little effect on efficiency, but is associated with an increase in prices . . . .").

41. Blue Cross & Blue Shield United of Wis. v. Marshfield Clinic, 65 F.3d 1406, 1412 (7th Cir. 1995).

42. FTC v. Tenet Health Care Corp., 186 F.3d 1045, 1054 (8th Cir. 1999).

43. See, e.g., Garabet v. Autonomous Techs. Corp., 116 F. Supp. 2d 1159, 1172 (C.D. Cal. 2000) (holding that divestiture should not be ordered without substantial evidence that the benefit outweighs the harm).

44. California v. American Stores Co., 495 U.S. 271, 284 (1990).

45. Ash Grove Cement Co. v. FTC, 577 F.2d 1368, 1380 (9th Cir. 1978).

46. Opinion of the Commission, In re Evanston Northwestern Healthcare Corp., FTC Docket No. 9315 (Aug. 6, 2007), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9315/070806opinion.pdf.

47. Gautam Gowrisankaran et al. Mergers When Prices Are Negotiated: Evidence from the Hospital Industry, 105 Am. Econ. Rev. 172, 196 (Jan. 2015) ("[S]eparate negotiations do not appear to solve the problem of bargaining leverage by hospitals.").

48. Brief of Amici Curiae Economics Professors in Support of Plaintiffs/Appellees Urging Affirmance, St. Alphonsus et al. v. St. Luke’s Health, No. 14-35173 (9th Cir. Aug. 20, 2014).