Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Fall 2021, Vol. 31, No. 2

Content

- A Litigator's Perspective On the Evolving Role of Economics In Antitrust Litigation

- Chair's Column

- "COMPETITION POLICY IN ITS BROADEST SENSE": CAN ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT BE A TOOL TO COMBAT SYSTEMIC RACISM?

- Editor's Notes

- Fairness Requires the Elimination of Forced Arbitration

- Jeld-wen: Opening the Door To Private Merger Challenges?

- Masthead

- On Being a Transwoman Lawyer...

- Patents and Antitrust In the Pharmaceuticals Industry

- Ten Years Post-therasense: Closing the Gap Between Walker Process Fraud and Inequitable Conduct

- The Consumer-welfare Standard Should Cease To Be the North Star of Antitrust

- The Evolution of Antitrust Arbitration

- An Economic Perspective On the Usefulness of the Consumer Welfare Standard As a Guiding Framework For Antitrust Policy

AN ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE ON THE USEFULNESS OF THE CONSUMER WELFARE STANDARD AS A GUIDING FRAMEWORK FOR ANTITRUST POLICY

By Lawrence Wu and Craig Malam1

I. INTRODUCTION

In the area of antitrust, the consumer welfare standard is under fire. This is not the first time. In 1978, noted legal scholar and judge, Robert Bork, made the case that the purpose of antitrust law was to protect consumer welfare.2 He could not have been more clear when he stated that "[t]he only legitimate goal of antitrust is the maximization of consumer welfare."3 At the time, this was a controversial opinion as antitrust policy was largely focused on other goals, such as protecting small business owners.4 Maximization of consumer welfare as the goal of antitrust policy also challenged existing perspectives because it was made at a time when the application of economics to antitrust was fairly new, and possibly not well accepted.5 But in the 30 years that followed, Bork’s view of antitrust policy prevailed.6 Indeed, in 2007, when the Antitrust Modernization Commission concluded its review of the antitrust laws, it seemed to most that there was little to debate when it came to the goals of antitrust policy. As the Commission stated in the introduction of the report, "[f]ree trade, unfettered by either private or governmental restraints, promotes the most efficient allocation of resources and greatest consumer welfare."7

The debate is back, though. In an article titled "Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox," which famously references the title of Robert Bork’s influential 1978 book, The Antitrust Paradox, Lina Khan—now the Chair of the Federal Trade Commission—describes her view of the goals of antitrust policy quite differently:

the current framework in antitrust—specifically its equating competition with "consumer welfare," typically measured through short-term effects on price and output—fails to capture the architecture of market power in the twenty-first century marketplace. In other words, the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance are not cognizable if we assess competition primarily through price and output. Focusing on these metrics instead blinds us to the potential hazards.8

[Page 46]

In Khan’s view, not only is consumer welfare the wrong standard, focusing on consumer welfare as the goal of antitrust policy is a mistake and inconsistent with the legislative intent of the antitrust laws, which was meant to be a "safeguard against excessive concentrations of economic power."9

In this paper, our goal is not to discuss the legislative intent of the antitrust laws or what it should be, nor are we focused on examining whether the courts have made decisions that are consistent with the consumer welfare standard. Instead, our aim is to give an economic perspective on the consumer welfare standard and to explain its practical and theoretical usefulness as a framework, whether the goal of antitrust policy is to maximize consumer welfare or some other goal such as protecting the "process of competition." In Section II, we define and discuss what consumer welfare means from the perspective of an economist. In Section III, we discuss whether, how, and why consumer welfare is a useful metric for evaluating competition and monopoly. There are criticisms of the consumer welfare standard, however, and in Section IV, we discuss one particular criticism, which is that the consumer welfare standard is wrongly focused on short-term price effects and on the outcome of the competitive process.10 We offer a few concluding comments in Section V.

Our conclusion is that the consumer welfare standard is a reasonable and practical framework for antitrust practitioners, enforcement agencies, the courts, and policymakers. This is because focusing on consumer welfare is consistent with economic theory and with the empirical approaches that make antitrust analysis such a data-driven and evidence-based area of law. FTC Chair Lina Khan and others have questioned whether the consumer welfare standard can be a guiding framework for antitrust policy. In our view, it can, and the way to address the concerns that have been raised is not to change the standard, but to improve the theoretical and empirical economic models and tools that will enable the enforcement agencies, courts, and policymakers to make policy decisions that will ensure that the benefits of price and non-price competition will remain in the short term and long term.

II. THE CONCEPTS BEHIND CONSUMER WELFARE AND CONSUMER SURPLUS

The OECD defines consumer welfare in terms of the "individual benefits derived from the consumption of goods and services."11 This is a fairly general description of what many people have in mind when they talk about consumer welfare, but it is useful because it explains why aggregate consumer welfare is used synonymously with the economic concept

[Page 47]

of consumer surplus.12 From an economic perspective, consumer surplus is a concept that is much easier to describe and analyze—it is the difference between the price that consumers are willing to pay for a good or service and the price that consumers actually pay for that good or service. The benefit or consumer surplus to any one individual is therefore derived from the fact that he or she paid less for that good or service than what he or she was willing to pay for it. For example, if the price of a cup of coffee is $2.99, consumers who are willing to pay more than $2.99 get consumer surplus from buying that cup of coffee at $2.99. Consumers who are willing to pay exactly $2.99 get to enjoy their coffee, but they would not get any consumer surplus. And consumers who are not willing to pay more than $2.99 for a cup of coffee would not buy that cup, and would also therefore not get any consumer surplus. The benefit to all consumers in aggregate (i.e., aggregate consumer welfare) would therefore be the sum across each individual’s consumer surplus.

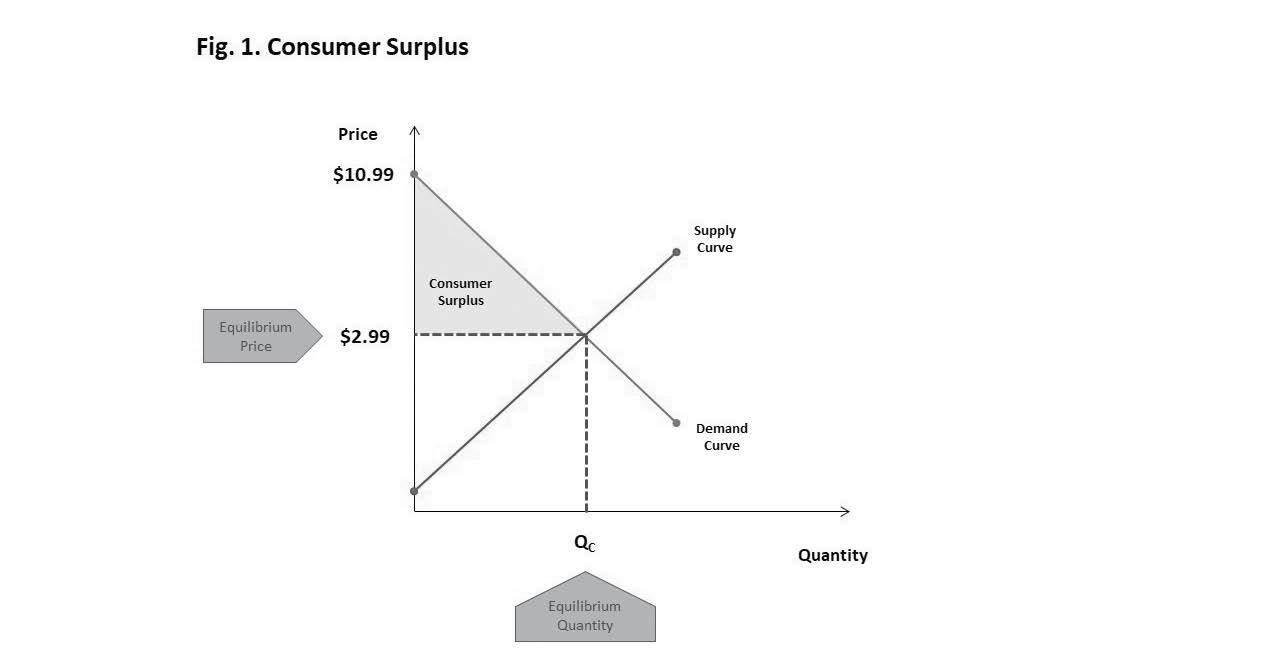

Visually, we can see this in Figure 1, which is a stylized graph of the supply and demand for a particular good or service (e.g., a cup of coffee).13 The demand curve is downward sloping because when the price is lower, the quantity demanded is more. This is because when the price is lower, it is likely that more consumers will demand the good or service and/or consumers will buy more of the good or service. The supply curve is upward sloping because when the price is higher, producers have an incentive to supply more of the good or service. The intersection of the two curves is called the equilibrium point, and that is where demand equals supply. It is at that point that the price is in equilibrium. At the equilibrium point, the price is at the level where the amount of goods and services demanded by consumers equals the amount of goods and services that are produced. In Figure 1, the equilibrium price for a cup of coffee is $2.99. That is the price that consumers pay for a cup of coffee, even if they are willing to pay more.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 48]

The consumer surplus across all individuals is visually shown as the shaded triangle that is underneath the demand curve, but above the $2.99 price (which is the point at which supply equals demand). The shaded area captures the consumer surplus of an individual that is willing to pay $10.99 for a cup of coffee; the consumer surplus of someone willing to pay $5.99 for a cup of coffee (which is $3 for this consumer); the consumer surplus of someone willing to pay $4.99 for a cup of coffee (which is $2 for this consumer); and so on until we have captured the surplus of everyone who is willing to pay $2.99 or more for a cup of coffee. This total is the consumer surplus that is generated when the price of a cup of coffee is $2.99.14

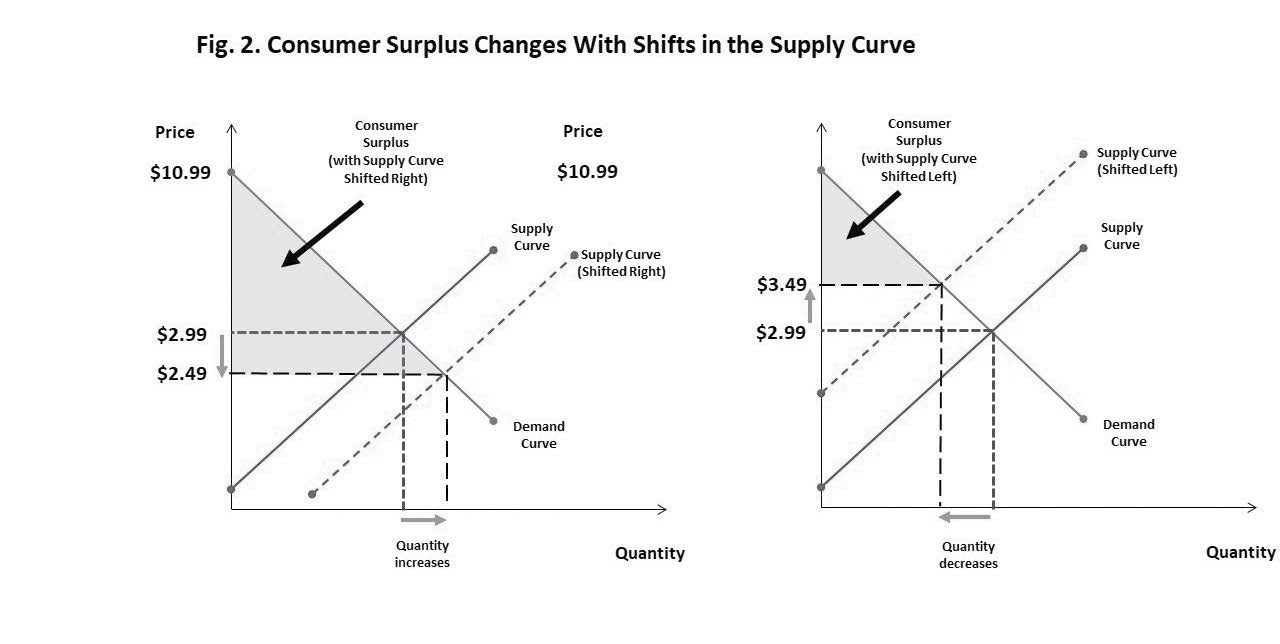

The panels in Figure 2 make it clear how important the supply curve is in determining how much consumer surplus will be generated. If the price were to fall (because, for example, producers innovate and learn how to make the good or service more cheaply), the aggregate consumer surplus would increase. This change would be represented by a rightward shift of the supply curve. When the supply curve shifts to the right (as shown in the left panel of Figure 2), more supply of the good or service can be made available at a given price. This would happen if suppliers were to improve their productivity, lower their costs, and expand their capacity. Because these changes in supply will push the market price down (to $2.49 for example), there are two effects on consumer surplus. First, everyone who was willing to buy a $2.99 cup of coffee would now pay less for that cup. Second, the drop in price would induce even more consumers to buy a cup of coffee. For example, at a price of $2.99 for a cup of coffee, a consumer might buy a cup every other day. But if the price were to fall to $2.49, the consumer might start to buy that cup of coffee every day.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 49]

The opposite effect occurs when the supply curve shifts to the left (as shown in the right panel of Figure 2). Causes of a leftward shift in the supply curve (of coffee) could include a freeze in Brazil that leads to a shortage of coffee beans or an increase in the cost of transporting beans from farm to table. If, for example, the price were to increase from $2.99 to $3.49, fewer consumers would end up buying that cup of coffee and there would be less consumer surplus as a result. This is because the only consumers buying that cup of coffee would be those who were willing to pay $3.49 or more. And for each of those consumers, the difference between how much they are willing to pay for that cup of coffee and the price that they actually paid just got smaller.15

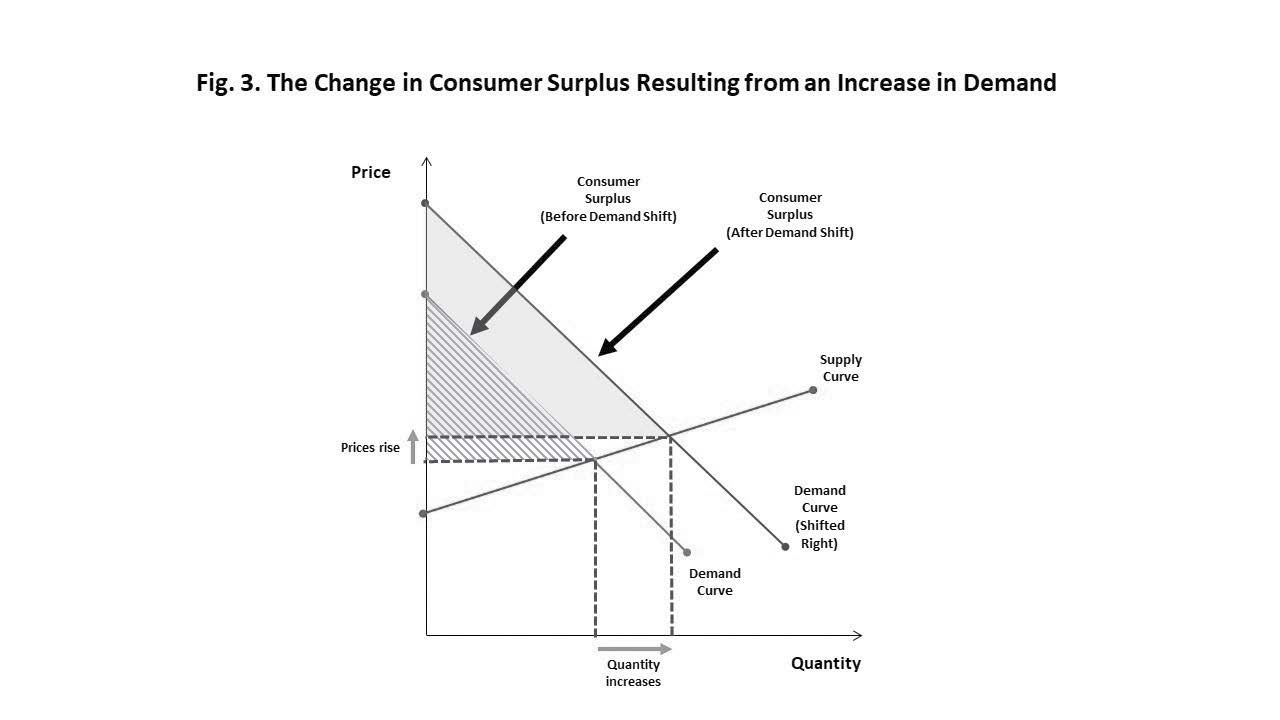

Similarly, shifts in demand also will affect consumer surplus. This is shown in Figure 3 below. Before the shift in demand, the consumer surplus is the striped area. If the demand for coffee were to shift to the right because new research showed that coffee was good for your health, then the price of coffee would rise. At the same time, the amount of coffee demanded would increase. This is because the equilibrium point shifted to the right and up along the supply curve. The consumer surplus that is generated by the shift in demand is the area shaded. As drawn, the consumer surplus after the shift in demand (i.e., the shaded area) is larger than the consumer surplus before the shift in demand (i.e., the striped area). Figure 3 is therefore an illustration of how an increase in demand can lead to an increase in consumer welfare. A price increase might not seem like something that would increase consumer surplus, but if prices rise only by a little, and many more people are buying coffee, then the shift in demand would lead to an increase in consumer surplus.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 50]

With this definition of consumer surplus and these concepts in mind, we can now turn to a discussion of whether, how, and why consumer surplus is a useful metric when it comes to evaluating competition and monopoly.

III. CONSUMER SURPLUS AS A MEASURE OF COMPETITION

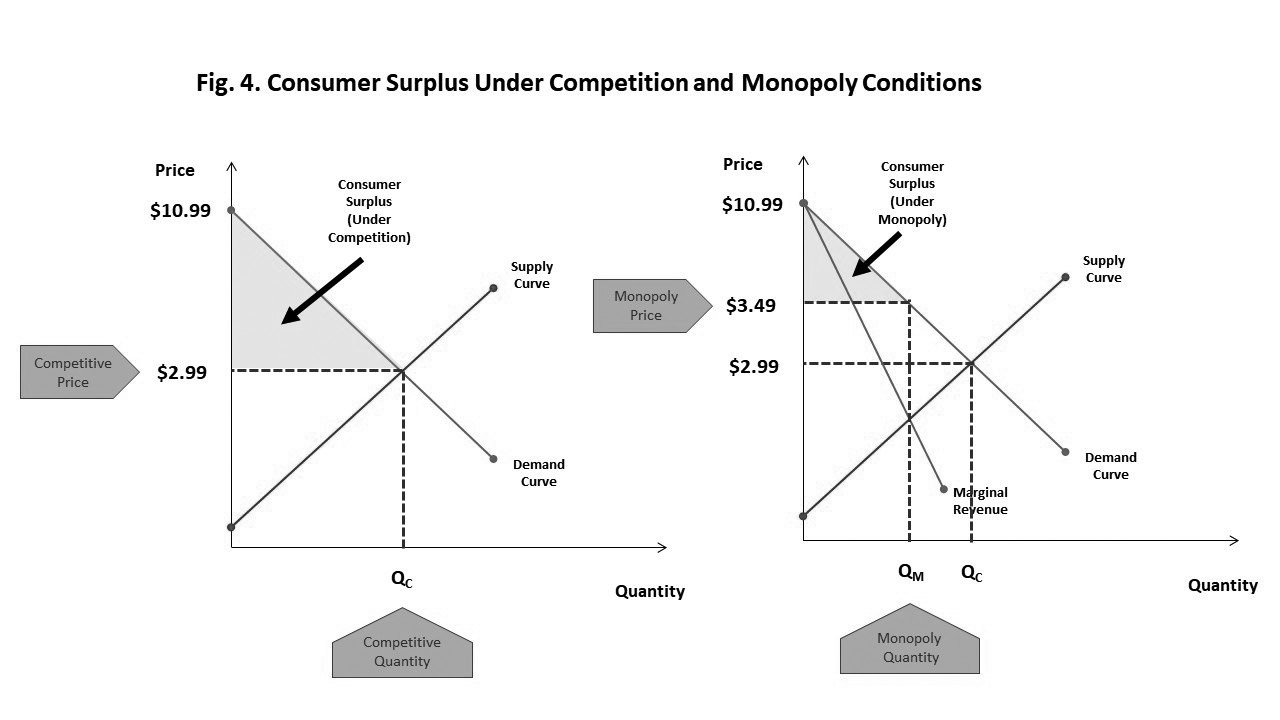

The supply and demand graph in Figure 1 describes the textbook market outcome under conditions of perfect competition. The price is where supply equals demand and the consumer surplus is the shaded area. If that same market were to be monopolized, the demand curve would not change, but the price that consumers would pay would change. Figure 4 shows the difference. The graph in the left panel illustrates the competitive outcome, which is the same graph shown in Figure 1. The graph in the right panel illustrates the monopoly outcome. A monopolist would produce the amount of good or service that equates marginal revenue with marginal cost. As shown in the right panel of Figure 4, the monopolist would only make QM units of the good or service. The monopolist would set the price that consumers are prepared to pay for the amount of the good or service that the monopolist actually made. As illustrated in Figure 4, the monopolist could sell everything that it produced (QM) if it charged a price of $3.49 because QM is the total quantity that consumers would demand at that price of $3.49. A comparison of the two panels makes it clear that consumer surplus is lower under monopoly conditions than under perfect competition. The individual preferences that shape the demand curve are the same, but the market price is higher. As a result, consumer welfare is lower for two reasons. First, there is a loss in consumer surplus because the consumers who continue to buy their cup of coffee from the monopolist are now paying more for their cup. Second, there is a loss of consumer surplus because some consumers are no longer buying coffee or, perhaps, buying coffee once a week instead of every day or every other day.

Image description added by Fastcase.

The comparison that is shown in Figure 4 illustrates why consumer welfare is, in general, lower when markets are less competitive. A price fixing cartel that conspires to raise price from $2.99 to $3.49 would reduce consumer surplus in the same way that the monopolist did (as shown in the right panel of Figure 4). Similarly, an attempt by a firm to engage in

[Page 51]

anticompetitive conduct may reduce consumer surplus if that conduct successfully resulted in the exit of competitors and the creation of monopoly power. That exit can lead to reduced consumer surplus in the direction as shown in the right panel of Figure 4.

Conversely, consumer surplus can be positively affected when firms engage in activities that could help them compete more effectively, expand output, and/or improve the quality of the goods and services they sell. For example, if a firm innovates and finds a way to produce with greater economies of scale, the result would be a rightward shift in the supply curve and an increase in consumer surplus. This is the situation that is shown in Figure 2, as discussed above. As shown in Figure 2, a rightward shift in the supply curve leads to an increase in consumer surplus for two reasons. First, there is a gain in consumer surplus because the consumers who were buying coffee at $2.99 can now purchase their coffee at a lower price ($2.49). Second, consumer surplus increases because there are now "new" consumers that were previously priced out of the market. At the lower price, some consumers may decide to buy coffee every day instead of every two days or once a week. And at the lower price, there may be an influx of new coffee drinkers.

The competition and monopoly scenarios shown in Figure 4 are extremes but they illustrate the main point, which is that a change in consumer surplus is a good measure of competitive impact. Activities that harm competition lower consumer surplus and activities that enhance competition increase consumer surplus. However, in many instances, the activities that are the subject of an antitrust investigation or litigation are those that could have positive and negative effects on competition and consumers in the short run and/or long run. Consider the following examples:

- Predatory pricing: An allegation of predatory pricing may refer to below-cost pricing that leads to the permanent exit of competitors and therefore the longer-term potential to raise prices above competitive levels. In the short run, prices may be below competitive levels (which would increase consumer surplus). However, with the exit of competitors, prices could rise in the long term if entry or re-entry by competitors does not occur (which would reduce consumer surplus). Focusing on both short-run and long-run consumer welfare, as measured by consumer surplus, provides a useful framework for thinking about the overall competitive impact of predatory pricing. This is because an analysis of consumer surplus in each of the various stages of predation can help in an assessment of the dynamics of predation that are inherent in this theory of competitive harm.

- Monopsony power: Allegations of monopsony power involve claims that a firm has the ability to pay below-market prices to its suppliers. Suppose, for example, there is evidence that the input prices paid to suppliers are lower in areas where the purchaser (i.e., the firm with potential monopsony power) accounts for a larger share of the purchases that are made. Because paying lower prices also may enable the purchaser to lower its costs and therefore the prices that it charges to customers, such evidence also may explain why that purchaser also has more business and sales. If the purchaser was exercising monopsony power, the purchaser would be paying lower prices for its inputs, but charging its customers higher prices or simply not extending the discounts that they would have offered in a competitive environment (either of which would reduce output and result in a reduction in consumer surplus). However, if the purchaser was lowering its costs and passing along those cost savings to their customers in the form of lower prices, then the result would be an increase in output and therefore an increase in consumer surplus. Here again, focusing on the metrics that affect both short-run and long-run consumer welfare (e.g., the prices paid by the alleged monopsonist for inputs, the level of output that is produced, and the final goods prices charged to downstream customers) provides a useful framework for identifying monopsony power and distinguishing such conduct from the ordinary efforts of a firm that is trying to lower its input costs and final goods prices.

- Exclusive territories: Sellers that have exclusive territories sometimes find themselves the target of antitrust investigations or litigation. For example, the concern may be that the exclusive territories are a way for the sellers to allocate geographic markets. On the other hand, the sellers may say that they created exclusive territories in order to give their local distributor(s) a stronger incentive to compete against distributors that carry other competitors’ brands. In these types of cases, it is important to distinguish harm to competition from harm to a competitor and the consumer welfare framework gives us a way to do that. Market allocation and other efforts that discourage entry into new areas restrict supply and reduce consumer surplus. However, efforts to give distributors greater incentives to compete and to make investments to increase sales would shift the supply curve to the right, which would increase consumer surplus. As with the examples above, focusing on consumer welfare (i.e., consumer surplus) provides a useful framework for an assessment of the overall competitive effect.

- Proposed mergers and acquisitions: A merger or acquisition could be subject to review by an antitrust agency. The agency may recognize that the transaction could have the potential of reducing competition with the result being higher prices, a reduction in quality competition, or less innovation. However, the agency also may recognize that the transaction could lead to economies of scale and other cost savings that could lead to lower prices, or combinations that create new products and increase variety. Because both effects are possible, the agency must consider the net effect of the transaction. A consumer welfare framework would allow the competition authority to do that. Indeed, the economic models that are often used to assess and/or simulate the impact of proposed transactions consider and account for the potential for a transaction to simultaneously eliminate the rivalry that exists between the merging parties (which would reduce consumer welfare), and for its potential to lower costs and therefore prices (which would increase consumer welfare).

[Page 52]

As the examples above illustrate, the consumer welfare standard is useful because it can be applied generally to a variety of anticompetitive actions and can handle many types of potential competitive harms. In the case of predatory pricing, the consumer welfare framework can be used to assess conduct that may have beneficial short-term effects, but more harmful long-term effects. In the case of monopsony pricing, the consumer welfare framework can be used to differentiate procompetitive bargaining by suppliers from anticompetitive reductions in input prices. In the case of exclusive territories (and exclusionary conduct more generally), the consumer welfare framework can be used to assess conduct that could have either anticompetitively restricted competition across geographies or encouraged procompetitive investments. And in the case of proposed

[Page 53]

mergers, the consumer welfare framework can be used to assess the net effect of a transaction (or conduct) that may generate economies of scale and other efficiencies.

IV. ADDRESSING THE CRITICISM THAT THE CONSUMER WELFARE STANDARD IS FLAWED OR INADEQUATE

Recent calls to find a new framework for antitrust policy and a move away from the consumer welfare standard seem to be motivated by a concern that focusing on consumer welfare has led to an underenforcement of the antitrust laws. A related concern is that the focus on consumer welfare may have caused us to miss important ways in which firms may acquire or exercise market power. Indeed, FTC Chair Lina Khan has argued that underenforcement of the antitrust laws is a consequence of an antitrust policy that is focused too much on short-term price effects.16

The specific criticisms of the consumer welfare standard take a number of different forms. One argument is that in the modern age, antitrust policy needs to pay more attention to the long-term consequences of a proposed transaction or some alleged misconduct. Another argument is that the protection of non-price competition and competition for innovation is just as important as the protection of price competition. A third argument is that evidence of short-term price competition is not a guarantee that there won’t be harm in the future. And a fourth argument is that enforcement should be focused on the process of competition, as opposed to outcomes such as price, output, quality, and innovation. These may seem like very different arguments, but they have a common theme, which is that focusing on the short-term effects of some conduct or transaction reflects a myopic approach to antitrust enforcement.

These arguments, however, are not really about the standard that one ought to apply when developing and implementing antitrust policy. This is because an analysis of consumer welfare does not rule out analyses of long-term effects. Nor does an analysis of consumer welfare imply that quality competition, innovation, and other forms of non-price competition get short shrift or are somehow less important than price competition. Even if we were to adopt an entirely different standard, these fundamental issues do not go away. For example, suppose we were to adopt a standard that focuses on protecting the "process of competition."17 One could still put too much emphasis on the process of competition in the short term and miss the long-term consequences, and one could inadvertently focus on how companies are competing on price, but overlook the process by which companies are competing on quality and innovation.

Moreover, even if one were to focus on protecting the process of competition, an assessment of consumer welfare would still be a valuable aspect of the analysis. Competition is expected to lead to lower prices, higher output, higher quality, and more innovation, which suggests that these basic elements of consumer surplus would only further or complement any other analysis that one might want to do to assess the "process of competition."

The arguments offered highlight an important issue, though, which is that policy decisions may require an assessment of opposing and complex questions. For example, should concerns about the long-term consequences take priority over the short-run changes that

[Page 54]

reflect innovation? Should policymakers sacrifice the benefits that come from economies of scale and scope to ensure that markets don’t become too highly concentrated in the future? Should policymakers protect small firms, even if they are inefficient, to ensure that there are an adequate number of competitors in the future? Is the importance of non-price competition receiving adequate recognition? These are important policy questions for the enforcement agencies, policymakers, and the courts, and they are being asked today under a consumer welfare framework. And even if one were to consider other policy goals, there is no reason why one would not want to consider consumer welfare in assessing any of these questions.

If the concern is that the consumer welfare standard is leading to underenforcement of the antitrust laws, we can address that directly by being careful and thoughtful in how we apply the consumer welfare standard in practice. That is because it is up to antitrust practitioners and the enforcement agencies to ensure that enforcement decisions are based on analyses that are data-driven and consistent with economic theory. To do that, we can keep in mind a number of principles.

First, we should keep in mind that antitrust analysis is largely a situation-specific inquiry that requires a high degree of data and market-specific facts. This means that we must collect accurate data needed to do the empirical analyses that are most relevant and informative. If we want to avoid focusing on short-term price effects, then we should press for the collection and analysis of data on quality, innovation, and other aspects of non-price competition. For example, data on product improvements and innovation, as well as total market output, would be informative. These metrics are not new and they are completely consistent with a framework that rests on the importance of consumer welfare.

In addition, by focusing on these metrics, we can continue to perform the empirical analyses and quantitative modeling that the courts and enforcement agencies have found valuable over the years. Of course, we should be cognizant that we don’t suffer from the myopia of focusing only on the things that we can measure. Opposing parties may disagree on the facts, but asking the right empirical questions, getting and analyzing the data, applying the right economic model that matches the underlying theory of competitive harm, and interpreting the results are all part of a reliable antitrust analysis.

Second, we should keep in mind that many theories of competitive harm are dynamic in that they specify actions that have consequences in the short term, and potentially different consequences in the long term. If we want to avoid focusing on short-term consequences and pay more attention to the longer term consequences, we can by developing the economic models that are needed to assess whether a consumer welfare-enhancing effort in the short run is likely to have adverse competitive effects over the longer term. There is nothing about the consumer welfare standard that prevents the consideration of such longer-term effects. There may be disagreement with respect to (a) whether the conditions are in place for future harm to competition, (b) if it is likely that competition will be harmed in the long term, and (c) how much weight should be given to these longer-term consequences, particularly if there is little evidence that consumers are harmed in the immediate term. Indeed, opposing parties may disagree on the likelihood of future harm and the weights that should be given to long-term effects over short-term effects, but this is the discussion that we can have within the consumer welfare framework.

[Page 55]

Third, we should keep in mind that much of antitrust analysis is a forward-looking inquiry. This is particularly the case with respect to analyses of proposed mergers and acquisitions and in the investigation of ongoing and current business practices. In today’s economy, markets can evolve and change quickly. But there is nothing in the consumer welfare framework that prevents or discourages an inquiry into how markets are likely to evolve over time.

In forward-looking analyses, there is also the potential to make Type I and Type II errors. Specifically, there is the cost of blocking activity that is not anticompetitive (a Type I error) and there is the cost of not blocking activity that is anticompetitive (a Type II error). Those who believe that there has been underenforcement of the antitrust laws would say that it is always more costly to make a Type II error than a Type I error. Thus, they argue that greater enforcement efforts are needed to reduce the likelihood of making Type II errors. Those who believe that it is more costly to make a Type I error than it is to make a Type II error would make the opposite argument. They would argue that the enforcement agencies should intervene only if they are sure that the activity or conduct at issue is anticompetitive.

Both types of errors are costly, and to reduce these errors, we should develop the economic models and evidence that will enable the enforcement agencies and courts to minimize both types of errors. In this respect, we should improve the precision and predictive power of the economic models that are applied, and we should continue to evaluate and test the models that are used and the assumptions behind those models. It is commonplace for policymakers and regulators to consider the error costs associated with their policies and enforcement decisions, and antitrust policy is no exception, whether consumer welfare is the goal of the antitrust laws or not.

Fourth, there is no substitute for making sure that we understand the market at issue and the nature of competition in that market. This is how we can ensure that antitrust analysis can focus on both the process of competition and on the indicia that are correlated with consumer welfare. From an economic standpoint, that means understanding the underlying economic theory of competitive harm and, importantly, the counterfactual world that would result if the merger did not happen or the counterfactual world that we would have observed had there not been the alleged misconduct. This is the analysis that will ultimately help us to ensure that antitrust is focused on protecting the competitive process and distinguishing harm to a competitor from harm to competition. These are fundamental economic issues and questions, and they have helped to make antitrust a discipline that is grounded in economic theory and empirical analysis. A rigorous approach that is rooted in economic theory and statistical and econometric analysis is the way antitrust is currently practiced, and with the greater availability of data and robust statistical tools to analyze these data, there is every reason to continue applying sound economic principles and empirical methods in antitrust, whether consumer welfare is the primary goal of the antitrust laws or not.

V. CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

From an economic standpoint, the consumer welfare standard is a useful framework for antitrust policy. Consumer welfare (with consumer surplus as its metric) is a framework that can be applied to many different types of antitrust issues and conduct. Importantly, consumer surplus is measurably lower as a result of the actions that the antitrust laws are often concerned about—monopolization, price fixing, mergers, exclusionary conduct, and buyer power. In addition, there are many benefits of having a standard that is based on consumer welfare.

[Page 56]

Such a standard is consistent with economic theory and it provides antitrust practitioners, enforcement agencies, the courts, and policymakers with objective indicia with which to assess and implement competition policy.

There are criticisms about the usefulness of the consumer welfare standard. Critics point to the potential for the standard to overemphasize the short-term price effects over other effects, such as non-price effects and effects that may occur in the long term. However, consumer welfare can be analyzed in the short run or the long run. There is nothing in the standard itself that gives short-run price effects greater weight or importance. Moreover, an antitrust framework that is based on consumer welfare as a goal does not imply that quality competition, innovation, and other forms of non-price competition are somehow less important than price competition.

If the concern is that the consumer welfare standard is leading to underenforcement of the antitrust laws, we can address that directly in four ways. First, we can press for better data and more reliable and informative empirical analyses, especially with respect to non-price competition. Second, we can develop the economic models that are dynamic and capable of assisting in an assessment of the long-term effects, especially when there are consumer welfare-enhancing efforts in the short run that could have adverse competitive effects over the longer term. Third, we should recognize that there are Type I and Type II costs in any enforcement activity and since both types of costs are important, we should improve the precision and predictive power of the economic models that are applied. Fourth, we should continue to appreciate that harm to competition is not the same as harm to a competitor, which means that there is no substitute for understanding the underlying competitive process and the nature of competition in the market at issue.

We live in a complex economy, which means that markets are complex. Modern markets also can change quickly. There is no question that both the complexity and dynamics of the modern economy make antitrust a challenging area of law and economics, but that is exactly why the economic approach to antitrust is so important. The concept of consumer welfare is a key element of the economic approach and therefore a useful framework for antitrust. If there are concerns that antitrust has given short-term price effects more importance, that is not because we have an antitrust policy that is focused on consumer welfare. The consumer welfare standard is robust and flexible enough to incorporate assessments of price and non-price effects in both the short term and long term.

Moreover, we can address concerns about the underenforcement of the antitrust laws within a consumer welfare framework. To do that, antitrust practitioners, enforcement agencies, the courts, and policymakers should continue to look at all angles, demand rigorous analysis, and encourage efforts to improve the power and usefulness of the economic models and tools that are used. This is a solution that does not involve moving away from consumer welfare as a guiding framework. Instead, it is a solution aimed at ensuring that all of the issues are considered and that the inquiry goes beyond analyses of the short-term price effects that are more immediate and easier to quantify and assess.

[Page 57]

——–

Notes:

1. Lawrence Wu is an economist and President of NERA Economic Consulting. Craig Malam is an economist and Associate Director at NERA Economic Consulting. The authors thank John Scalf and Paul Wong for their very thoughtful comments and discussion.

2. ROBERT H. BORK, THE ANTITRUST PARADOX: A POLICY AT WAR WITH ITSELF (1978).

3. Id. at 7.

4. See Kenneth Heyer, Consumer Welfare and the Legacy of Robert Bork, 57 J.L. & ECON. S19, S20 (2014).

5. Id. at S23.

6. Steven C. Salop, Question: What Is the Real and Proper Antitrust Welfare Standard? Answer: The True Consumer Welfare Standard, 22 LOYOLA CONSUMER L. REV. 336-53 (2010).

7. ANTITRUST MODERNIZATION COMM., REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS i (April 2007).

8. Lina M. Khan, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 126 THE YALE L.J. 710, 716-717 (2017).

9. Id. at 743.

10. See generally Id.; Tim Wu, After Consumer Welfare, Now What? The ‘Protection of Competition’ Standard in Practice, COMPETITION POLICY INT’L (Apr. 2018), available at https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2291; Herbert J. Hovenkamp, Is Antitrust’s Consumer Welfare Principle Imperiled?, 45 J. Corp. Law 101 (2019), available at https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1985; Leon B. Greenfield et al., Antitrust Populism and the Consumer Welfare Standard: What Are We Actually Debating?, 83 ANTITRUST L.J. 393 (2020); Elyse Dorsey et al., Consumer Welfare & the Rule of Law: The Case Against the New Populist Antitrust Movement, 47 PEPPERDINE L. REV. 861 (2020).

11. Directorate for Financial, Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs, OECD, Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law (R. S. Khemani & D. M. Shapiro ed. 1993), https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=3177.

12. As noted by Jonathan Jacobson, "[t]he consumer welfare standard equates with consumers’ surplus in economic terms…" Jonathan M. Jacobson, Another Take on the Relevant Welfare Standard for Antitrust, THE ANTITRUST SOURCE, August 2015, at 2.

13. The graphs in this paper are stylized in that the demand and supply curves are drawn as linear functions of price (i.e., straight lines). Although supply and demand curves can take on any number of functional forms, the linear supply and demand graphs in this paper are still useful in illustrating and explaining the basic economic propositions and concepts that describe how the amount of consumer surplus in a market is calculated and affected by the degree of competition in the market and by shifts in supply and demand.

14. The way to think about consumer surplus is the same, whether demand is elastic (in which case the demand curve would be flatter) or inelastic (in which case the demand curve would be more steep). When demand is elastic, the quantity that consumers buy is more sensitive to price. When demand is inelastic, the quantity that consumers buy is not as sensitive to price. The demand for a good or service may be inelastic and less sensitive to price if there are fewer substitutes for the good or service, or if the good or service was particularly important or valuable. Whether demand is elastic or inelastic will affect the amount of consumer surplus in the market. For example, consider the supply and demand graph in Figure 1 and what would happen if the demand curve were to be rotated around the equilibrium point in such a way that the demand curve was flatter (and therefore more elastic). The area under the demand curve would be smaller, which means that the amount of consumer surplus would be less.

15. There are many factors that would affect whether a shift in the supply curve is likely to lead to a large or small change in consumer surplus. One such factor is the elasticity of demand. If the demand curve is more inelastic, a rightward shift in supply would lead to a greater increase in consumer surplus. At the other extreme, if the demand curve were completely elastic (i.e., perfectly flat), a rightward shift in supply would not lead to any increase in consumer surplus.

16. Greenfield, supra note 10 at 404.

17. See, for example, the "Protection of Competition" standard that was put forward by Tim Wu. Wu, supra note 10.