Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Fall 2021, Vol. 31, No. 2

Content

- A Litigator's Perspective On the Evolving Role of Economics In Antitrust Litigation

- An Economic Perspective On the Usefulness of the Consumer Welfare Standard As a Guiding Framework For Antitrust Policy

- Chair's Column

- "COMPETITION POLICY IN ITS BROADEST SENSE": CAN ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT BE A TOOL TO COMBAT SYSTEMIC RACISM?

- Editor's Notes

- Fairness Requires the Elimination of Forced Arbitration

- Jeld-wen: Opening the Door To Private Merger Challenges?

- Masthead

- On Being a Transwoman Lawyer...

- Ten Years Post-therasense: Closing the Gap Between Walker Process Fraud and Inequitable Conduct

- The Consumer-welfare Standard Should Cease To Be the North Star of Antitrust

- The Evolution of Antitrust Arbitration

- Patents and Antitrust In the Pharmaceuticals Industry

PATENTS AND ANTITRUST IN THE PHARMACEUTICALS INDUSTRY

By DeForest McDuff, Ph.D., Mickey Ferri, Ph.D., and Noah Brennan, M.I.A.1

I. INTRODUCTION

Patent rights are a core element of protecting innovation in the United States. The pharmaceutical industry is often identified as an example of the patent system working well, by compensating innovators for research and development and then allowing competition after innovators have been rewarded. Over the past 10-15 years, however, there has been increased concern of anticompetitive behavior associated with prolonged patent protection, which has led to a number of antitrust lawsuits attempting to restrain the long duration of exclusivity.

Antitrust enforcement efforts have had mixed success to date, depending primarily on whether the efforts are focused on patent-based strategies versus market-based strategies. Patent-based strategies relying purely on seeking additional patents on existing products, such as evergreening and patent thickets, have been difficult to address in the antitrust domain because of constitutional rights to seek patents. By contrast, market-based strategies impacting the availability of competing products, such as product hopping and reverse payments, have shown to be more susceptible to antitrust enforcement. The distinction in effectiveness appears to stem from the legal system’s stronger ability to identify anticompetitive conduct in the market domain, compared to the pursuit of patentable innovations in good faith.

Ultimately, antitrust enforcement efforts in the last decade have shown that foundational principles of protecting competition through the antitrust laws serve the public interest well, with some room for policy improvement around the edges, not necessarily limited to antitrust law, in order to address aspects of market exclusivity that are specific to the pharmaceutical industry.

[Page 127]

This article proceeds as follows: Section 2 describes the economic framework for patent protection and why it has caused potential for certain economic incentives and unintended consequences. Section 3 describes antitrust enforcement as a framework for limiting potential excesses of the patent system that may cause anticompetitive behavior. Section 4 provides a public policy evaluation of antitrust enforcement and other policy initiatives designed to limit extreme outcomes that may be socially undesirable. Section 5 concludes.

II. PATENT PROTECTION

A. A Brief History

The grant of exclusive property rights vested in patents has a long history, tracing back to medieval guild practices in Europe.2 The very first Article of the U.S. Constitution established the intellectual property clause providing for the patent system, which instructs Congress to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries" (emphasis added).3 The Patent Act of 1790 originally included a patent term duration of 14 years from patent issuance.4

The legal system has reinforced the effectiveness of the patent system, developing rules and procedures to enforce the rights of patentees and their assignees. For example, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, the intellectual property expert of the early courts, offered this perspective in Ex parte Wood: "[T]he inventor has …a property in his inventions; a property which is often of very great value, and of which the law intended to give him the absolute enjoyment and possession … involving some of the dearest and most valuable rights which society acknowledges, and the constitution itself means to favour."5 Congress has adapted the law to improve the system, including the Patent Act of 1836 that introduced an examination system that is still in use today, whereby each patent application is scrutinized by technically trained examiners to ensure that the invention conforms to the law and constitutes an original advance in the state of the art.6

The term length of issued patents has also undergone revision over time. The Patent Act of 1836 originally increased the term from 14 years to 21 years from issuance. In 1861, the term was changed to 17 years. The signing of the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act changed the patent term from 17 years from the date of issuance to 20 years from the earliest filing date, which remains active today.7

[Page 128]

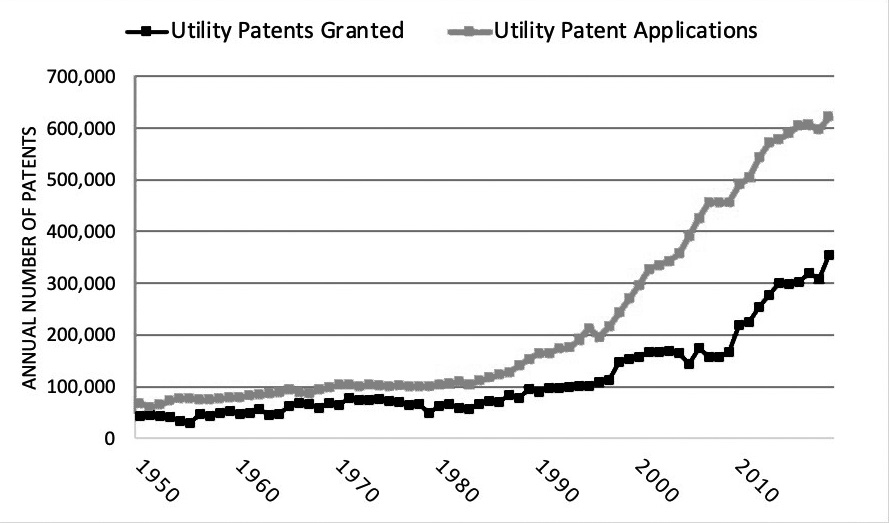

In the last few decades, the number of patents and patent applications has increased dramatically. See Figure 1. For example, data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) show that the number of utility patent applications increased from just over 100,000 in 1979 to over 600,000 in 2019. Similarly, the number of utility patents granted grew from nearly 50,000 in 1979 to more than 350,000 in 2019. Said another way, there were nearly 1,000 new patents granted per day in 2019.8 In the context of the increasing volume of patents in recent years, it is worth evaluating the role of patents in the overall economy, including the economic trade-offs between patent holders, consumers, and potential competition.

Figure 1. U.S. Patent Activity (1950-2019)

Image description added by Fastcase.

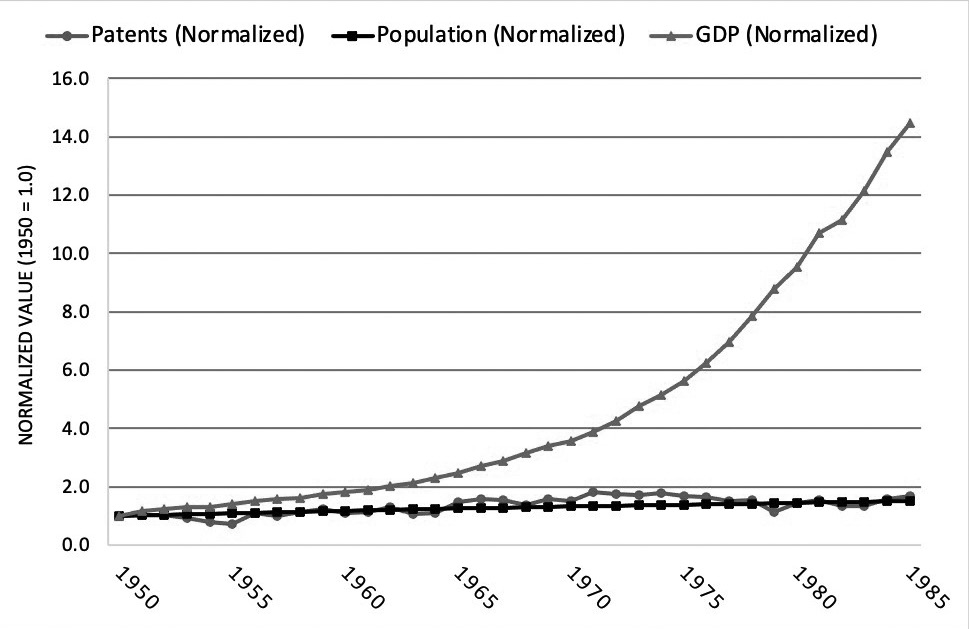

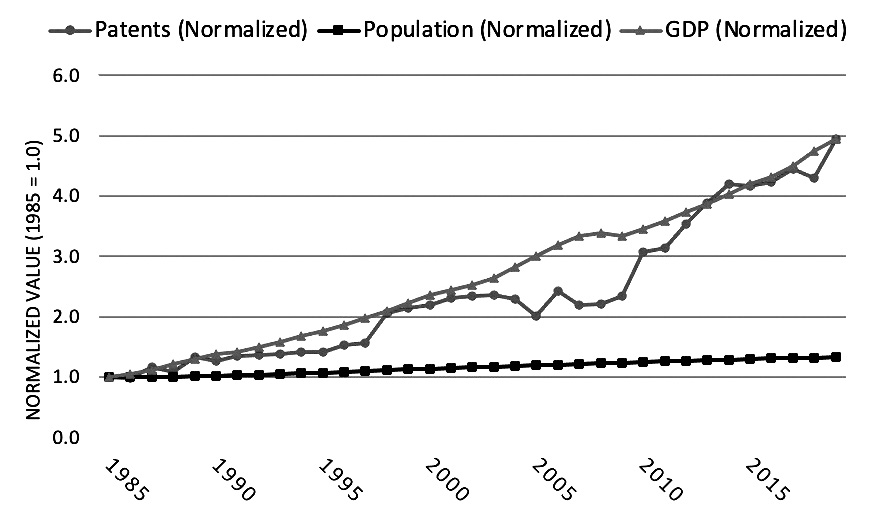

A comparison between patent grants, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), and population growth show that growth in patents has become more correlated with growth in GDP in recent years, with both growing faster than the population.9 This trend can be seen by separating the data into two time periods: (1) 1950 to 1985 and (2) 1985 to 2019.10 First, from 1950 to 1985, GDP growth far outpaced both patent growth and population growth. See Figure 2.A. Annual GDP in 1985 was 14.5 times its 1950 level, while annual patent grants were 1.7 times their 1950 level and population was 1.5 times its 1950 level. By comparison, from 1985 through 2019, GDP growth closely aligned with patent growth, while population growth was far lower. See Figure 2.B. Using 1985 as the base year,

[Page 129]

the 2019 levels of both GDP and patent grants were 4.9 times their 1985 levels, while population growth was just 1.3 times its 1985 level.

The pattern that growth in patents has been aligned with GDP growth beginning in 1985, yet not in the prior period, is generally consistent with commentary and analysis from a number of sources on the increasing contribution of capital (which includes intellectual property such as patents) and decreasing contribution of labor to the U.S. economy over the past few decades.11

Figure 2.A Patents, Population, and GDP (1950-1985)

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 130]

Figure 2.B Patents, Population, and GDP (1985-2019)

Image description added by Fastcase.

B. Economic Incentives and Unintended Consequences

As a matter of economics, patent rights are typically justified based on allowing inventors to recoup returns on investments in research, development, and regulatory approval.12 Economically, a profit opportunity is larger for a patent holder who has the exclusive right to make, use, or sell a patent protected product as compared to a profit opportunity in a competitive market, with competition from other suppliers. The large potential profit opportunity from a patented drug with high demand can incentivize research and development, which can lead to scientific and medical advances that benefit consumers and patients. Data from the USPTO indicate that patents related to "Pharmaceuticals and Medicines" comprise approximately 5% of all utility patents granted.13

Patent protection in pharmaceuticals is of particular importance because pharmaceutical research and development costs for individual drugs can be substantial, with many drugs costing billions of dollars and a decade or more to bring a new drug to market. One study published in JAMA in 2020 found that the median capitalized research and development investment to bring a new drug to market was estimated at $985.3 million and the mean

[Page 131]

investment was estimated at $1.3 billion.14 Other studies have reported similar findings, including estimated mean costs of developing a single new therapeutic agent in the multiple billions of dollars when all economic costs are included, with recent estimates in economic literature and medical literature of $2 to $3 billion per new drug.15

In addition to the monetary research and development costs, substantial time typically passes from the initial drug discovery, research & development, and patent filing, through clinical trials and regulatory approval until the eventual product launch. One study in 2016 indicated that the process of drug development can take 15 years, with 3-5 years of drug discovery, 1-2 years of pre-clinical time, 6-7 years of clinical trials, and 1-2 years of regulatory approval.16 Another study found that the average time from the start of clinical testing to marketing approval was 8.1 years.17 Further, there is an economic risk that the drugs may never make it to market. One study found that the overall probability of clinical success (i.e., the likelihood that a drug that enters clinical testing will eventually be approved) was just 12%.18

In pharmaceuticals, the period of exclusive patent protection can sometimes be limited if the duration of development is long. For example, if a product launches 13 years after the earliest filing date, the patent holder may have limited years of exclusivity to follow. From a profit maximization perspective, the patent holder will often have strong economic incentives to make as much profit as possible during this period of exclusivity. When generic competition enters, revenues and profits earned by the patent holder can fall substantially. For example, according to an FDA study using data on generic entry from 2015 through 2017, generic prices were lower than the reference product by an average of 39% with one generic competitor, 54% with two generics, and 68% or greater as generic competition increases.19

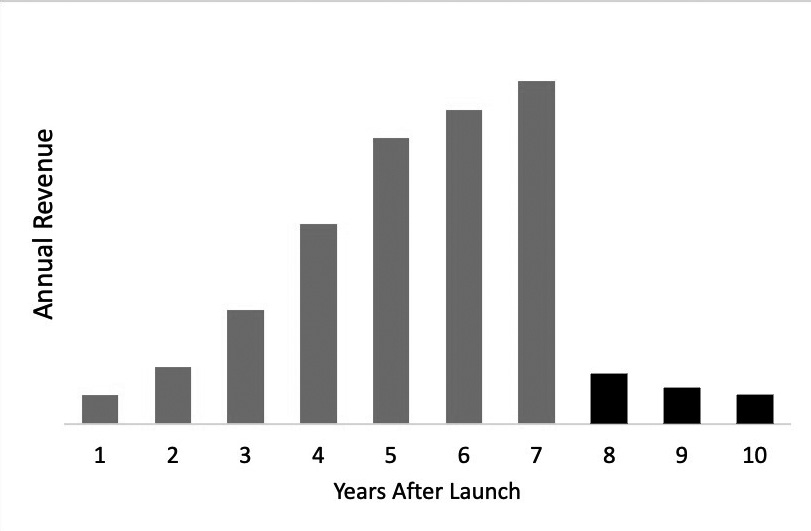

Despite the importance of patent protection in the pharmaceutical industry, the economic dynamics described above can lead to some unintended consequences. When pharmaceutical products successfully launch under patent protection, there can be large annual profits during the period before the relevant patents expire. For patent holders, extending patent protection by a few more years may be worth hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars by delaying generic competition that can take market share from the reference product. Strategies to stave off competition can be immensely valuable, even if for just a short time longer. The following figure illustrates the potential impact and thus dollars at stake for a patent holder facing generic competition, such that extending patent

[Page 132]

protection for a few additional years may have a substantial impact on the overall revenue earned over the product life cycle:

Figure 3. Illustrative Revenue Profile of a Pharmaceutical Product

Image description added by Fastcase.

In the case of pharmaceuticals and patents, incentives provided by patent rights have the potential to create economic misalignment with the goals of the system. In recent years, patent holders have sought ways to extend the period of exclusive rights for products,20 through strategies such as evergreening and product hopping, all discussed in more detail in Section 3. While each patent has a term limited to 20 years from earliest filing date, the collective set of patents provides a period of exclusivity that can be much longer. The trade-off between exclusivity to encourage innovation, on the one hand, and lower prices for consumers, on the other hand, has been a historical source of policy tension. In 1984, for example, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act to tweak the balance between the competing interests of innovation and competition by rewarding generic competitors who challenge patents held by pharmaceutical companies.21 The Act provides for an Abbreviated New Drug Application ("ANDA") process for generic drug manufacturers, whereby rather than undergoing lengthy preclinical and clinical periods, they simply have to show bioequivalence to an already-approved drug.22

In recent years, the economic incentives provided by the patent system have led to some products with an extremely long duration of market exclusivity. For example, one recent study found that the 12 top grossing drugs of 2017 had an average duration of

[Page 133]

market exclusivity of 38 years (and up to nearly 50 years for some products!),23 well beyond the 20-year duration that is provided by any single patent.

All of this begs relevant questions for law and policy, such as "How long is too long?" and "If we agree that some market exclusivity appears to be too long, what is the best law and policy to curb the duration?" We address those questions in the context of antitrust enforcement as one potential pathway in Section 3 and more broadly in public policy in Section 4.

III. ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT

A. Overview

Given the economic incentives to extend patent protection for branded pharmaceutical products, it is not surprising that some companies have identified strategies to extend patent life. The most notable and observed strategies in the pharmaceutical industry can broadly be described as: (1) patent-based strategies, which relate to seeking additional and sometimes excessive numbers of patents (e.g., evergreening and patent thickets); and (2) market-based strategies, which relate to seeking patent protection from product-based coordination (e.g., product hopping and reverse payments). In response to each of these strategies, would-be competitors and government regulators have alleged potential anticompetitive behavior on the part of the patent holders by employing these strategies. In this section, we discuss what these strategies are, why anticompetitive behavior has been alleged, and how these cases have been evaluated by the courts.

Antitrust enforcement efforts by potential competitors, government regulators, and others can best be understood as an attempt to use existing antitrust laws to "fix" the potential economic distortions and/or unintended consequences described above. As discussed, patent protection provides rights granted by the U.S. Constitution designed to encourage, protect, and reward innovation. In some cases, however, it appears that competition may be stifled or at least reduced due to individual incentives to extend patent protection beyond what patent policy is designed to protect.

It is important to distinguish the difference between the meaning of "patent monopoly" for an invention compared to "monopoly power" in the context of antitrust law. When a patent holder has a patent monopoly right, the patent legally protects the patent holder’s particular invention and enables it to maintain its temporary monopoly over use of a specific invention. Once the patent expires and the exclusivity period ends, the patent holder loses its legal right to a monopoly. By contrast, monopoly power in an antitrust context refers to market power and certain market shares that have been achieved via competition and/or anticompetitive conduct.24 According to the Supreme Court, market power is "the ability to raise prices above those that would be charged in a competitive market,"25 and

[Page 134]

monopoly power (at least for Sherman Act § 2 cases) is "the power to control prices or exclude competition."26 Yet the exclusive right over a specific invention, as granted by a patent, does not necessarily lead to market or monopoly power for the product as a whole if the patented product competes with other products, patented or not, in a competitive marketplace. For pharmaceutical products, there are important distinctions between patent exclusivity (i.e., exclusive rights to practice an invention), product exclusivity (i.e., exclusive rights to produce a product free of generic competition), and market exclusivity (i.e., being the only product in a competitive market).27 Indeed, the Supreme Court has stated: "a patent does not necessarily confer market power upon the patentee."28

From a policy perspective, we want to encourage competition and legitimate patent protection, but we would also like to discourage certain market exclusivities that may result from unintended consequences of the patent system. Potential distortion can occur, for example, if companies use the patent system to prevent or discourage competition above and beyond the duration or scope of what the patent system is designed to protect. In such a circumstance, the patent protection being granted to a company may provide too much economic reward at the expense of competition.

The solution, some have argued, is to bring antitrust actions against companies who have sought to extend exclusivity protection beyond what is intended by the law. If actions are taken with the intent of stifling competition rather than pursuing protectable innovations in good faith, then antitrust enforcement may be a potential solution. But, how to distinguish between legitimate patent protection and violations of antitrust law remains a challenge and was articulated at the heart of the landmark California Supreme Court opinion In re Cipro on reverse payments:29

To protect competition in the marketplace, antitrust law prohibits agreements that create or perpetuate monopolies. Patent law, in contrast, grants temporary monopolies to inventors to encourage the development of useful innovations. We consider here a crucial question at the intersection of these two bodies of law: what limits, if any, does antitrust law place on the ability of a patent holder to make agreements restricting competition during the life of its patent?

This question has additionally been raised in the courts in a number of contexts, described as follows.

[Page 135]

B. Patent-Based Strategies

Patent-based strategies refer to efforts by patent holders to prolong patent exclusivity by covering an existing product with numerous or additional patents. While individual patents provide 20 years of invention exclusivity, pharmaceutical products may enjoy market exclusivity from generic competition as long as one or more valid patents covering the products remain. Those commercializing patented products benefit if the period of restricted competition is strengthened or lengthened through additional patents. Two main types of patent-based strategies have been engaged in by patent owners and challenged in the courts are commonly known as: (1) patent thickets and (2) evergreening.

[1] Patent thickets. One patent-based strategy pharmaceutical manufacturers are alleged to have engaged in is the creation of "patent thickets" around profitable drugs. A patent thicket refers to many patents covering a single product such that would-be competitors deem it too costly or risky to challenge all of the patents (i.e., they are deterred by the "thicket" of patent protection). The effect is that the patent holder is able to reap the economic rewards of unchallenged product exclusivity.

Evidence indicates that the prevalence of patent thickets is growing over time. For example, the average number of patents per drug rose from 1.9 for drugs approved between 1985 and 1987 to 6.1 for drugs approved between 2012 and 2014.30 Patent thickets are especially salient for blockbuster drugs, with an average of 71 issued patents (!) among the 12 top grossing drugs of 2017.31

Branded drug manufacturers argue that creating complex blockbuster drugs is difficult work that requires numerous subsequent innovations. Detractors claim the patent thickets may contain obvious or minor incremental innovations that provide little consumer benefit and detract from potential generic or biosimilar use. Examples of patent thicket allegations, or allegations that could impact the ability to maintain a patent thicket, in the antitrust context include:

- In Re: Humira (Adalimumab) Antitrust Litigation (N.D. Ill. 2020): The plaintiffs in this case (indirect purchasers of Humira) alleged that defendant AbbVie "created a thicket of intellectual property protection so dense that it prevented would-be challengers from entering the market with cheaper biosimilar alternatives" in violation of § 2 of the Sherman Act. Despite noting that AbbVie’s 100-plus patents contributed to Humira’s profitability, the court ruled this did not constitute an antitrust violation, stating: "AbbVie has exploited advantages conferred on it through lawful practices and to the extent this has kept prices high for Humira, existing antitrust doctrine does not prohibit it." Further, the court found AbbVie’s conduct before the USPTO in pursuing the patents at issue was not objectively baseless and concluded with respect to patents and antitrust law that: "[t]he patent prosecution system is no doubt imperfect, but… the proper fix is not to use antitrust doctrine…."32

- In Re: Lantus Direct Purchaser Antitrust Litigation (1st Cir. 2020): The plaintiffs in this case (direct purchasers of insulin glargine) alleged that defendant Sanofi improperly listed a patent in the FDA Orange Book as purportedly covering the insulin product "thereby delaying competition in the insulin glargine market and resulting in inflated prices" in violation of § 2 of the Sherman Act. At first, the district court dismissed the Sherman Act claims on the reasoning that the decision to list the patent was not objectively baseless. However, the First Circuit vacated the district court’s dismissal, finding that Sanofi is potentially liable under antitrust laws. Although Sanofi argued that any improper patent listings were objectively reasonable, the First Circuit stated that it must show "that the challenged conduct be both reasonable and in good faith," and remanded for further proceedings to answer these questions.33

[Page 136]

[2] Evergreening. A second patent-based strategy frequently implemented is called "evergreening," which involves seeking additional patents on an already patented product as the existing patents approach expiration. Rather than face competition as an unprotected product, patent exclusivity is effectively reset (i.e., "evergreened") with the issuance of the subsequent patents. Research indicates seeking additional patents is frequently pursued among manufacturers of branded pharmaceutical products, with 78% of drug products associated with newly issued patents were existing drugs as opposed to new drugs.34 Further, 70% of the 100 best-selling drugs extended patent protection at least once, and 50% extended more than once.35

The debate over whether evergreening constitutes anticompetitive behavior typically centers around the significance and timing of the follow-on development. Patent holders often describe subsequent patents as innovative developments that benefit consumers, while detractors of the practice allege that follow-on patents are trivial and intended to earn more profits rather than improve patient health. Examples of evergreening allegations in the antitrust context include:

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Ben Venue Labs., Inc. (D.N.J. 2000): The defendants in this case asserted counterclaims against Bristol-Myers Squibb, alleging fraudulent procurement and enforcement of patents in violation of § 2 of the Sherman Act. The district court noted that "[A]ntitrust liability under section 2 of the Sherman Act may arise when a patent has been procured by knowing and willful fraud, the patentee has market power in the relevant market, and has used its fraudulently obtained patent to restrain competition," and concluded the Hatch-Waxman defendant had standing to bring Sherman Act claims.36 After an April 2001 Federal Circuit opinion affirmed a district court ruling that certain patent claims were invalid,37 the parties settled litigation,38 which included the mutual release from all actions based on any alleged monopolization or attempted monopolization.

- Robert Nichols, et al. v. SmithKline Beecham Corp. (E.D. Pa. 2005): Plaintiffs in a class-action suit against GlaxoSmithKline alleged that GSK violated § 2 of the Sherman Act by "stockpiling and causing patents to be listed with the [FDA] in a manner which enabled [GSK] to unlawfully extend its market monopoly for Paxil by delaying FDA approval of generic paroxetine hydrochloride." Specific allegations include misleading the USPTO into issuing invalid patents and defrauding the FDA by submitting those patents for listing in the Orange Book to wrongfully exclude competition by generic manufacturers. After a 2004 Federal Circuit opinion in another case found a key patent invalid, and GSK delisted two others patents from the Orange Book, the parties in this case began settlement negotiations. Ultimately, the court approved a $65 million settlement paid by GSK to end this antitrust litigation.39

[Page 137]

Indeed, some pharmaceutical follow-on patents have even been alleged to be "double patents," i.e., second patents that are not patentably distinct from claims in a first patent. Though typically addressed through litigation related to patent validity (i.e., not antitrust), double patents represent the same core issue: whether patent protection has been improperly extended. Examples of recent cases involving double patenting include:

- Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. v. Eli Lilly and Co. (Fed. Cir. 2010): The Federal Circuit affirmed a district court judgment that asserted claims in that case were invalid for obviousness-type double patenting over an existing patent. The Federal Circuit noted two types of double patenting: (1) statutory, which prohibits a patent covering the same invention, and (2) obviousness-type, which prevents a later patent from covering a slight variation of an earlier patented invention. The Federal Circuit acknowledged the market exclusivity granted by a patent when it stated the specification of the earlier issued patent may be consulted to assess the utility of an invention, since double patenting rejections "rest on the fact that a patent has been issued and later issuance of a second patent will continue protection, beyond the date of the expiration of the first patent" (emphasis in original).40

- Immunex Corp. v. Sandoz, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2020): In a 2018 bench trial, the district court held that defendant Sandoz failed to show the asserted claims of the patents-in-suit were invalid. Although the Federal Circuit agreed that the plaintiff in this case did not run afoul of double patenting laws (because double patenting can only apply if the patents share common ownership), the Federal Circuit emphasized the importance of the double patenting doctrine to reduce improper patent protection, stating: "Obviousness-type double patenting is a judicially-created doctrine aimed at preventing claims in separate patents that claim obvious variants of the same subject matter where granting both exclusive rights would effectively extend the life of patent protection."41 In May 2021, the Supreme Court denied a petition to review the case.

[Page 138]

C. Market-Based Strategies

Market-based strategies refer to efforts by a patent holder to prolong patent exclusivity through actions intended to influence the marketplace outside of, or in addition to, the pursuit of additional patents (e.g., by impacting the availability of competing products). While strategies of this type are in some sense intended to preserve exclusivity, that goal is sought by actions that are separate from patent protection. Two main types of market-based strategies have been engaged in by patent owners and challenged in courts: (1) product hopping and (2) reverse payments.

[1] Product hopping. Product hopping refers to transitioning consumers from a product that is approaching the end of its patent exclusivity to a new, but similar, patent-protected product. The similar product may have a new form factor (e.g., switching from/to a capsule, tablet, injection, or other form), a new drug release profile (e.g., extended release rather than immediate release), a different combination of active ingredients, or some other modification.

Like the patent-based strategy of evergreening described above, the debate surrounding the desirability of product hopping focuses on the perceived significance of the product improvement. Here, too, patent holders often describe the subsequent products as significant improvements, while opponents often claim the new products represent minor incremental improvements and detract from generic use of the original drug. A second issue concerns the degree to which the manufacturer encourages product switching, ranging from "hard switches" in which the original product is removed from the market, to more "soft switches" in which the original product is kept on the market, but a product transition is encouraged by means such as the shifting of marketing and promotion expenditures, among others. Examples of product hopping allegations in the antitrust context include:

- Abbott Laboratories v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. (D. Del. 2006): In 1998, Abbott received FDA approval for a capsule version of the cholesterol-lowering drug TriCor. Teva and Impax filed ANDAs, upon which Abbott filed suit for patent infringement triggering a statutory 30-month stay of any FDA approval of the ANDAs. During the stay, Abbott filed an NDA for a tablet formulation and proceeded to remove the capsule version from the market by suspending sale of the capsule formulation and buying back pharmacy supplies of that formulation, among other actions. After a second round of tablet ANDAs, Abbott again filed suit triggering another 30-month stay. In counterclaims, the ANDA filers asserted violations of § 2 of the Sherman Act. Abbott moved to dismiss, but the district court rejected the motion and opined that Abbott prevented a consumer choice between products "by removing the old formulations from the market while introducing new formulations."42 The parties ultimately agreed to settle the case during trial.43

- Walgreen Co. v. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP (D.D.C. 2008): Walgreen alleged that AstraZeneca violated § 2 of the Sherman Act by deterring generic competition when it introduced a new heartburn drug, Nexium, just as patent exclusivity for its nearly identical drug, Prilosec, was about to expire. However, the district court granted a motion to dismiss, opining that "[t]he fact that a new product siphoned off some of the sales from the old product and, in turn, depressed sales of the generic substitutes for the old product, does not create an antitrust cause of action."44

- New York ex rel. Schneiderman v. Actavis plc (2nd Cir. 2015): Actavis, through its wholly owned subsidiary Forest Laboratories, removed virtually all of Namenda IR, a twice-daily Alzheimer’s drug, from the market shortly before its patent expiration and replaced it with Namenda XR, a once-daily version. The patents on Namenda XR granted defendants an additional 14 years of patent protection on the branded version of the drug. Plaintiffs argued that because drug substitution laws would not allow pharmacists to substitute the branded XR version for generic IR, a "hard switch" to Namenda XR would impede generic competition for the IR drug. The district court issued a preliminary injunction barring the defendants from restricting access to Namenda IR prior to generic IR entry. The Second Circuit affirmed this ruling stating that the defendants’ "hard switch crosses the line from persuasion to coercion and is anticompetitive," and that the plaintiff "has made a strong showing of irreparable harm to competition and consumers in the absence of a preliminary injunction."45

- FTC v. Reckitt Benckiser Group PLC (W.D. Va. 2019): The Federal Trade Commission filed suit against Reckitt regarding the opioid addiction treatment drug Suboxone, which was originally approved as a tablet in 2002. Reckitt, now known as Indivior, developed a dissolvable film version which was approved in 2010 and allegedly attempted to switch tablet customers to the film version by marketing it as reducing the risk of accidental pediatric exposure despite an earlier FDA rejection of this claim. Further, Indivior allegedly raised the price of the tablet above that of the new film version to coerce switching before discontinuing the tablet version in 2013.46 The parties settled the dispute, with Reckitt agreeing to pay $50 million, provide the FTC notice upon future follow-on product approvals, and be prohibited from destroying or withdrawing original product from the market.47

[Page 139]

[2] Reverse payments. Reverse payments are a second market-based strategy branded manufacturers may employ to prolong patent protection. Also called "pay-for-delay," reverse payments occur in the context of litigation between a competing company attempting to bring a generic product to market and the branded manufacturer. Specifically, reverse payments refer to when a branded and generic company settle litigation before the merits of the case, including patent validity, are settled and the plaintiff might pay the defendant (the reverse direction that one might expect) to refrain from entering the market until a certain date.

This strategy allows a branded company to avoid the risk of a patent being declared invalid and continue to earn economic profits as the exclusive supplier of a drug until the agreed upon date of generic entry. Examples of reverse payment allegations in the antitrust context include:

- FTC v. Actavis, Inc. (U.S. 2013): In 2009, the FTC filed a complaint challenging a reverse payment settlement between Solvay Pharmaceuticals and two generic drug manufacturers. The FTC argued that Solvay paid the generic manufacturers millions of dollars essentially to delay the release of the generic testosterone replacement drug AndroGel. The district court dismissed the complaint, and the Eleventh Circuit affirmed that ruling, opining that "absent sham litigation or fraud in obtaining the patent, a reverse payment settlement is immune from antitrust attack so long as its anticompetitive effects fall within the scope of the exclusionary potential of the patent." In 2013, the case was heard by the Supreme Court where the dismissal was reversed, permitting antitrust review of reverse payment settlements. The Supreme Court noted that "patent and antitrust policies are both relevant in determining the scope of the patent monopoly—and consequently antitrust law immunity—that is conferred by a patent."48 The Supreme Court stated that "a reverse payment, where large and unjustified, can bring with it the risk of significant anticompetitive effects," and the anticompetitive effects and potential justifications can be assessed without litigating the validity of the patent. In February 2019, the parties settled the case and the defendants were prohibited from entering into similar agreements.49 This opinion greatly influenced California antitrust law, when the California Supreme Court found patents are not presumptively "ironclad" for antitrust purposes (see discussion of In re Cipro below).

- FTC v. Cephalon, Inc. (E.D. Pa. 2015): In 2002, four generic drug manufacturers sought to make a generic version of Provigil, a Cephalon drug indicated to treat narcolepsy and other sleep related disorders.50 Cephalon paid over $200 million to settle the lawsuit and delay market entry until 2012.51 In 2008, the FTC sought injunctive relief related to the settlements under Section 13(b) of the FTC Act to prevent Cephalon from enforcing the settlements and engaging in similar agreements in the future. However, in 2011, the patent at issue was invalidated in a related case due to inequitable conduct in the patent procurement process. Generic Provigil then entered the market in 2012. Following the FTC v. Actavis decision, a status conference was held, during which the FTC indicated that it would "potentially be looking for some redress of the consumer harm that’s been caused by the years and years of delayed generic entry." Cephalon filed a motion to preclude the FTC from seeking disgorgement. The court ruled the FTC was permitted to seek disgorgement.52 Ultimately, the parties settled with Cephalon, which had been acquired by Teva, paying $1.2 billion into a settlement fund as equitable monetary relief.53

- In Re: Lipitor Antitrust Litigation (3rd Cir. 2017): From 2002 to 2008, Ranbaxy and Pfizer entered numerous litigations regarding patents including: (1) a 2002 Lipitor litigation, (2) a 2004 Accupril litigation, and (3) another 2008 Lipitor litigation related to two additional process patents. Not long after the second Lipitor litigation the parties entered into a near-global settlement agreement relating to multiple disputes. Per the terms of the agreement, Ranbaxy paid Pfizer $1 million in connection with the Accupril litigation in addition to delaying its generic Lipitor product until November 2011. Pfizer agreed to settle the Accupril litigation despite expressing confidence it would obtain a substantial monetary judgment from Ranbaxy. Direct-purchaser and end-payor plaintiffs then filed suit alleging Pfizer violated § 2 of the Sherman Act through the reverse payment. The district court dismissed the claims. On appeal, the Third Circuit ruled that "Lipitor plaintiffs have plausibly pled an unlawful reverse payment settlement agreement. Their allegations sufficiently allege that Pfizer agreed to release the Accupril claims against Ranbaxy, which were likely to succeed and worth hundreds of millions of dollars, in exchange for Ranbaxy’s delay in the release of its generic version of Lipitor," and that the dismissal of the Lipitor plaintiffs’ allegations was an error.54 As of the writing of this article, the case is ongoing.55

[Page 141]

In California, reverse payments have been addressed in state courts, Federal courts, and state legislation:

[Page 142]

- In re Cipro Cases I & II (Cal. 2015): In 2015, California’s Supreme Court weighed in on nine coordinated class action suits brought by indirect purchasers of the antibiotic Cipro. In 1987, Bayer was issued a U.S. patent on the active ingredient in Cipro that expired in December 2003. In 1991, Bayer filed suit, and Barr responded that Bayer’s patent was obvious and an invalid double patent, among other things. In early 1997, the parties settled, and Barr agreed to postpone marketing of its generic Cipro until the expiration of the Cipro patent. Bayer agreed to supply Barr with Cipro (at 85% of its current price) for licensed resale six months prior to patent expiration and made additional payments that totaled $398.1 million between 1997 and 2003 (a period during which Bayer’s profits from Cipro exceeded $1 billion). The trial court in this case found the agreement did not violate California’s Cartwright Act since it did not restrain competition longer than the exclusionary scope of the patent at issue, and the Court of Appeal agreed, stating restraint of competition within the scope of a patent was lawful unless the patent was procured by fraud or the suit to enforce it was objectively baseless. The California Supreme Court disagreed. Citing Actavis (see discussion of the Supreme Court case above), the California Supreme Court stated, "patents are in a sense probabilistic, rather than ironclad: they grant their holders a potential but not a certain right to exclude," further noting the mere fact "that a settlement resolves a patent dispute does not immunize the agreement from antitrust attack."56 Ultimately, the class settled with the defendants for a total of $399 million.57

- FTC v. Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc., et al. (N.D. Cal. 2017): In the Northern District of California, in 2017, the FTC filed suit against Endo Pharmaceuticals and a number of other entities alleging a reverse payment agreement to obstruct generic competition for Endo’s branded lidocaine patch Lidoderm. In 2012, in the face of generic competition from Watson, Endo and Watson entered into an agreement whereby, according to the FTC: (1) Watson agreed to delay generic launch for more than a year, (2) Watson agreed to abandon its related patent challenge, (3) Endo agreed to delay launch of an authorized generic to allow Watson a period as the only generic (i.e., a "no-AG commitment") worth hundreds of millions of dollars, and (4) Endo further provided Watson with branded Lidoderm patches valued between $96 to $240 million dollars that Watson could sell through its distribution subsidiary for profit.58 The FTC and Endo agreed to settle the case and another proceeding by entering into a stipulated order for permanent injunction, whereby Endo was prohibited for ten years from entering into patent infringement settlement agreements that contained a no-AG commitment or a payment by the NDA holder to the generic filer.59

- California Assembly Bill 824 (2019): As discussed in Section 4 below, the California law Preserving Access to Affordable Drugs (AB-824) took effect in 2020 with the goal of reducing reverse-payment patent settlements,60 and in July 2020, the Ninth Circuit dismissed a challenge to the statute.61

[Page 143]

D. Enforcement to Date

As the cases above show, disentangling legitimate patent protection from anticompetitive conduct has been challenging. The last 10 to 15 years have involved a number of antitrust enforcement attempts with mixed success to date.

For market-based behavior, antitrust enforcement has been successful in identifying violations and influencing market behavior. For example, reverse payments to keep generic competitors off the market have essentially stopped occurring, following successful enforcement in several cases. In 2006 and 2007, 40-50% of final settlements filed with the FTC contained reverse payments; by comparison in 2015 and 2016, no final settlements contained a side deal like that found in Actavis.62 Companies now think twice before paying a generic competitor to stay off the market. Similarly, in recent years, the most impactful forms of product hopping, such as pulling the predecessor product off the market (i.e., a switch that "crosses the line from persuasion to coercion and is anticompetitive"),63 have largely been identified by the courts. Especially with the FTC beginning to weigh in as in FTC v. Reckitt, we expect companies to further orient towards at least keeping old medicines available to patients and doctors who prefer them. In these areas, antitrust enforcement advocates can point to cases that have successfully reduced the prevalence of practices that are thought of as reducing competition.

On the other hand, antitrust enforcement has been less successful in combating practices related to patent-based behavior like evergreening and patent thickets. In these cases, challenges exist in determining whether patent practices are indeed anticompetitive actions, or simply protecting patentable innovations in good faith. Unlike reverse payments and product hopping, which have less to do with the validity or number of patents and more to do with directly evaluating potential anticompetitive behavior, evergreening and patent thickets allegations can be defended by arguments of simply seeking patents within the proper procedures of the patent system.

Said another way, the spectrum of successful antitrust enforcement appears to depend primarily on how easy it is to distinguish between clear anticompetitive behavior, such as paying a potential competitor to stay off the market, and legitimate patent protection (or not) when a company pursues dozens of patents or more on its products and a potential violation may be less clear. If companies engage with the patent system in good faith,

[Page 144]

seeking patent rights on protectable innovation, it may be difficult to determine when that crosses over into an antitrust violation, if ever.

Even in the more successful domains of enforcement, companies have modified behaviors in a way where some unintended economic consequences may still persist. Rather than paying a generic competitor to stay off the market, companies may instead simply negotiate the length of time a generic competitor should stay off the market before competing. In that context, is there anything inherently anticompetitive with a generic company agreeing to stay off the market until certain patent protection expires? After all, legitimate patent protection is a foundational goal and function of the patent system. Similarly, is there anything inherently anticompetitive with seeking more than 100 patents on a single pharmaceutical product? This volume of patents frequently occurs in other industries — computers, telecommunications, electronics, software — and that volume of patents may or may not be applicable or necessary for pharmaceutical products.

The product life cycle strategies described above clearly extend patent protection at the expense of competition, at least in the short run, but the question for policy is whether they extend patent protection too far — i.e., beyond what is socially desirable. If we think that some strategies extend product exclusivity for too long, then the goals of antitrust enforcement may be legitimate, even if an antitrust violation is difficult or impossible to establish.

From a social welfare perspective, we may want to discourage companies from extending patent protection on an individual pharmaceutical product for too many years, so that individual gains to innovating do not come at the expense of competition (or vice versa if the balance were tipped in the other direction). But there is still an open question for whether antitrust enforcement is the best means to achieve that goal. As the Northern District of Illinois court concluded with respect to antitrust claims based on a patent thicket: "The patent prosecution system is no doubt imperfect… [yet] the proper fix is not to use antitrust doctrine."64

Which leaves some questions. Are we satisfied with patent protection and antitrust enforcement to date, recognizing its successes but also its limits? Or do we think that new policy or legislation should be implemented to move the needle towards more competition in some circumstances? Some policymakers have introduced bills to tighten regulation and discretion in these areas. Ultimately, as described, the goal of the patent system is to balance innovation rewards with incentives for competition. With that goal in mind, what is the policy maker to do?

IV. PUBLIC POLICY

A. Public Policy Objectives

As a matter of economics, the goal of public policy is to evaluate trade-offs and collective action in order to harness economic self-interest and promote the common good. Public policy decisions are based on how policy impacts individual incentives, collective incentives, and the long-term success of a market economy and the society at large.

[Page 145]

For antitrust policy, the core economic trade-offs involve encouraging market success and economics of scale for business interests, on the one hand, while preserving and fostering competition for consumer interests, on the other hand. We would like private companies to grow, thrive, and seek economies of scale if they meet consumer demand and succeed in the marketplace, yet we also want to foster competition in the long run and prevent companies from maintaining market power through anticompetitive actions. For patents and intellectual property, the core economic trade-offs involve encouraging and rewarding innovation in the short run while allowing for the benefits of innovation to be shared by all in the long run. On the one hand, we would like new ideas and advances to generate economic value by granting economic rights to those who innovate. On the other hand, after those rewards are justly earned, we would like consumers and competing companies to be able to capture the economic benefits more broadly.

In both areas, the economic goal of public policy is to understand the economic trade-offs as best we can and design policy that best balances those trade-offs. If antitrust enforcement is too strong, then companies may be wary of growing and succeeding in the market for risk of penalty or being broken up; if antitrust enforcement is too weak, then companies may actively discourage competition by engaging in anticompetitive actions. If patent protection is too strong, then innovation is overrewarded with consumers paying monopoly prices for too long; if patent protection is too weak, then innovation is stifled since the incentives to innovate are not large enough. Successful public policy aligns rewards with those who create economic value. If antitrust enforcement has limitations, described above, then we should consider whether there are areas to improve that extend beyond what is currently available.

For the purposes of potential policy improvements, we start with the premise that at least some instances of patent protection appear to provide too much product exclusivity. There may be nothing wrong with legitimate patent protection, of course, but certain situations can extend the benefits of exclusivity beyond what is intended, as granted by the U.S. Constitution and designed in patent policy. With that starting point in mind, the policy objective would be oriented towards correcting some of the more extreme and impactful situations that deter reasonable competition. The question for policy, then, is how best to identify those situations and counteract them. In that regard, there are several avenues to consider for potential improvement.

B. Market-Based Strategies

We begin by addressing law and economic policy around market-based strategies, since current antitrust enforcement has had more success in that domain. Whereas strictly patent-based strategies have been difficult to address with antitrust enforcement, as discussed, market-based strategies can be addressed to some degree by the existing law. From that perspective, we evaluate several approaches for limiting unintended consequences like product hopping and reverse payments, starting with continued enforcement of existing efforts.

[1] Continue current enforcement efforts. One perspective is that current antitrust enforcement efforts are working as they should, by evaluating limits to competition and assessing whether and to what degree those limits promote a competitive market environment. Cases can be filed and adjudicated in the court system, as current

[Page 146]

practice already permits. While the track record over the last 10 to 15 years provides a range of successes in such enforcement, the net result has been a change in action among market participants reducing conduct that may be a violation.

Reverse payments are the most salient example where antitrust enforcement efforts have been successful in changing behavior. While the Supreme Court in FTC v. Actavis, did not find reverse payments to be per se illegal, the Court did describe why such circumstances could be anticompetitive, and then left lower courts to consider those cases on a case-by-case basis. As a result, according to the FTC, reverse payments in their most direct form have all but ceased.65

This is an example of how successful court enforcement flows back to the real economy. If court enforcement becomes predictable, as it did with reverse payments even without a determination of per se illegality, then behavior changes by market participants in a way that will avoid penalties down the line — in other words, a real correction to anticompetitive action that no longer occurs and no longer causes limits to competition. On the other hand, refinements to reverse payment strategies, such as parties mutually agreeing to delay competition, have been harder to enforce because determining whether such agreements to stay off the market are anticompetitive is harder.

To date, the authors have seen no evidence that antitrust enforcement efforts in these areas have systematically gone too far. While any single case may be subject to individual evaluation, the courts have not found many behaviors to be universally accepted as antitrust violations and, in fact, have tended to find violations in only the most extreme cases. On the whole, traditional economic principles of antitrust enforcement have been reiterated and applied to the best extent possible, and that is the best we can ask of our court system. If anything, more violations in gray-area cases may have been expected, given the public attention and long duration of exclusivity observed for many pharmaceutical products (e.g., a jury finding or court finding based on fairness and emotional appeal that patent protection may extend too far). The majority of the observed violations, however, strike the authors as having sufficient factual and economic support, at least as far as reasonable minds can see the arguments and courts have sufficient basis to rule in accordance with antitrust law.

As long as there are sufficient incentives for enforcement, either through public enforcement by regulatory agencies or private enforcement by harmed plaintiffs, then the practice of establishing parameters in which violations exist and enforcing those circumstances should, in the long run, tend towards better market outcomes as anticompetitive practices are reduced.

[2] Improve antitrust enforcement. The above discussion notwithstanding, some parties and lawmakers have expressed concern that current antitrust enforcement has not gone far enough, even for market-based strategies where there has been some traction in the courts. If antitrust laws as currently defined and historically enforced have not curbed certain unintended consequences of the patent system, proponents argue, then perhaps enforcement or even the laws themselves need to be expanded or refined.

[Page 147]

In a sense, this was the path that was sought by the government in FTC v. Actavis, which was considered and ruled by the U.S. Supreme Court. In that case, as discussed, the FTC sought to have reverse payments be deemed as a per se violation of antitrust doctrine. Such a finding would have had immediate impact on antitrust enforcement and reverse payment behavior. In that case, the Supreme Court commented specifically on the interplay between patent law and antitrust law in achieving proper balance of public policy through the law:

That form of [reverse payment] settlement is unusual. And … there is reason for concern that settlements taking this form tend to have significant adverse effects on competition. Given these factors, it would be incongruous to determine antitrust legality by measuring the settlement’s anticompetitive effects solely against patent law policy, rather than by measuring them against procompetitive antitrust policies as well. … [P]atent and antitrust policies are both relevant in determining the scope of the patent monopoly—and consequently antitrust law immunity—that is conferred by a patent.66

However, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Supreme Court did not find that reverse payments should be presumptively unlawful, and instead pointed to the traditional rule of reason analysis for determining whether or not a particular situation is anticompetitive:

The FTC urges us to hold that reverse payment settlement agreements are presumptively unlawful and that courts reviewing such agreements should proceed via a "quick look" approach, rather than applying a "rule of reason." We decline to do so. … [T]he FTC must prove its case as in other rule-of-reason cases.67

In other words, at least in this example, the Supreme Court showed resistance to extending the reach of antitrust law, even despite noting the "reason for concern" with reverse payments. Instead of actively redefining what would constitute a violation in this context, the Court relied on traditional notions and tests for how to evaluate antitrust conduct. In principle, while antitrust laws can be revised or enforced in a way that better encompasses the situations of public policy concern, this path seems less promising, given the duration and robust history of antitrust law itself, dating back to the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Accordingly, evaluating each circumstance on a case-by-case basis may be the best approach we have. If companies are colluding to benefit from market exclusivity at the expense of consumers, we can try to determine that factually and economically. If companies are merely seeking to recognize and negotiate over properly granted market exclusivity, we can approach that the same way. This is what the fact-based inquiry of the court system and rule of reason enforcement are all about, and perhaps that will remain the leading principle for enforcement.

[3] Legislate targeted extensions to enforcement. A third policy path forward in addressing market-based strategies involves new legislation that extends anticompetitive

[Page 148]

enforcement to specific situations that commonly come up and, in the eyes of the public and legislature, have not been adequately addressed by the court and thus have tilted the balance towards too much market exclusivity. In other words, if antitrust principles and active enforcement are in principle robust but not broad enough to curb specific exceptional unintended consequences, then lawmakers may want to address these specific circumstances with direct legislation.

The Hatch-Waxman Act (1984), described above, is a great example of this kind of approach, with a policy objective being achieved through legislation. From a policy standpoint, lawmakers were concerned that the patent system, as designed and implemented, did not give generic competitors strong enough economic incentives to challenge patents as invalid. Rather than fundamentally change the patent system, though, the legislature added the new policy to give patent challengers economic incentives to address the already functioning system.

A similar path forward of identifying and targeting specific legislation where economic distortions have occurred seems to the authors to be a viable path forward. In that sense, antitrust enforcement is not being fundamentally changed at first principles, it is just that specific undesirable situations, which may be near or just beyond the reach of antitrust enforcement efforts, can be corrected if we collectively decide that antitrust doctrine is not strict enough to foster the kind of competition we want as a society. Indeed, this kind of legislation has been considered over the past few years and is currently being considered today.

In California, the California law Preserving Access to Affordable Drugs (AB-824) took effect in 2020 with the goal of reducing reverse-payment patent settlements.68 The California law goes further than the rule of reason principle, stating a settlement agreement "shall be presumed to have anticompetitive effects and shall be a violation… if both the following apply: (A) A nonreference drug filer receives anything of value from another company asserting patent infringement, including, but not limited to, an exclusive license or a promise that the brand company will not launch an authorized generic version of its brand drug. (B) The nonreference drug filer agrees to limit or forego research, development, manufacturing, marketing, or sales of the nonreference drug filer’s product for any period of time."69 That is, where antitrust law reach a limit at the Supreme Court in FTC v. Actavis, California has legislated a specific type of circumstance that it wishes to stop. It remains to be seen, of course, how enforcement of this new code will play out.

At the federal level, proposals have been made but currently none have been passed. One example is the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, which was introduced as a bill in the Senate in 2019 and designed to "amend the Federal Trade Commission Act to prohibit anticompetitive behaviors by drug manufacturers, and for other purposes."70 Specifically, the bill defined product hopping as having several elements, including that the manufacturer engaged in a "hard switch" (e.g., withdrawing the reference product) or a "soft switch" (e.g., unfairly disadvantaging the reference product), and provided the FTC

[Page 149]

with the ability to identify and prohibit product hopping as anticompetitive behavior.71 The bill included remedies of disgorgement (i.e., giving back the profits earned) and restitution (i.e., restoring to the plaintiff what was taken).72

A second example federally is the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which was introduced to the Senate in 2019 and designed to "prohibit brand name drug companies from compensating generic drug companies to delay the entry of a generic drug into the market."73 Specifically, the bill referenced the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 and reverse payment actions that "allow a branded company to share its monopoly profits with the generic company as a way to protect the branded company’s monopoly," and defined "compensation for delay" as unlawful under the Federal Trade Commission Act.74

Neither national bill has been voted into law, though both were designed to extend anticompetitive enforcement to specific situations, the former for product hopping and the latter for reverse payments. Similar bills have been introduced "to reduce the impact of later-filed patents…; to facilitate generic market entry…; [and] to increase transparency as to the patents that cover biological products…."75 As recently as April 2021, versions of these bills along with two others were re-introduced into the House and Senate to re-engage with the goal of tweaking existing law and policy to curb some of the extreme outcomes of the current system.76

C. Patent-Based Strategies

For patent-based strategies, as discussed, antitrust efforts to date have thus far not been effective in reducing the unintended consequences of long durations of product exclusivity. Because the court system and we as a society value the constitutionally protected rights of patent holders, antitrust enforcement has not been a viable path to success for challenging whether products are protected by "too many" patents or for "too long." Thus, rather than refinement of antitrust doctrine or law, the public policy path forward may involve thinking more fundamentally about first principles of patent issuance and protection. Several proposals are discussed.

[1] Improve patent issuance at the USPTO. One approach is to focus on patent issuance at the USPTO. Better identification of valid patents with real contributions, proponents argue, would reduce overcompensating innovators for follow-on inventions that extend exclusivity for minor improvements.

The difficulty with this kind of approach, of course, is figuring out where to draw the line. In the trade-off between granting more patents on the one hand (i.e., nudging policy

[Page 150]

towards lower standards for issuance) versus granting fewer patents on the other hand (i.e., nudging policy towards higher standards for issuance), it is unclear which direction we should push. There is no systematic evidence that the authors are aware of that too few patents or too many patents are being awarded, and thus seeking improvements at the USPTO, while a fine pursuit in theory, may bear limited benefit in practice without more clearly defined objectives.

Proponents of this approach may argue for additional funding for the USPTO to increase the quality of patents being issued. While the authors have no disagreement with this idea, in theory, it is unclear whether "throwing money at the problem" will result in tangibly better outcomes. There is some evidence that patent grants have high variability across examiners, and that likelihood of appeal and reversal are higher than desired.77 Such variability may be mitigated by review from additional examiners, or other similar approaches. Better patent issuance is a desirable goal, if it can be achieved, that may pay for itself in economic benefits that flow back into the real economy. That said, further research on potential improvements from targeted approaches and additional funding seems warranted before pursuing this path too strongly.

[2] Focus on patent infringement remedies. Another approach to better aligning patent enforcement with public policy considerations is to focus on appropriate remedies for patent infringement. In this regard, the authors consider two primary remedies: (1) injunction: keeping a competitor off the market; and (2) damages: monetary award for infringement.

On injunction rights, one economic challenge associated with pharmaceutical patent enforcement is whether and to what degree incremental improvements from follow-on patents should allow for rights to enjoin competition. With strict requirements for bioequivalence for generic pharmaceuticals (and analogous clinical requirements for biologics and biosimilars), generic drug companies may be enjoined from competing and may be unable to design around less impactful follow-on patent protection.

As an example, let’s say a drug company has a dozen patents on its pharmaceutical product, ranging from patent protection on the chemical compound to formulations to methods of treatment to dosing — i.e., a full range of attributes of the product. Even if all developments were arguably innovative, they may differ in their degrees of contribution. A generic competitor may have no choice, due to FDA policy, to match all aspects of the reference drug product, even for less important attributes. As a result, the patent holder may be able to get injunction rights for its strongest and most innovative patents, but also for its weaker and less important patents. In such a situation, the interplay of the patent system (rights of exclusivity) and FDA policy (requirements for clinical equivalence) preserves the brand product monopoly for years after some of the earlier patents have expired. Is that a good result, from a policy perspective?

One issue here is that patent issuance is binary (either issued or not) and an injunction is also binary (either a competitor is enjoined or not). Injunction remedies may be more

[Page 151]

aligned with public policy objectives for foundational patents but less aligned for patents representing modest incremental improvements, whether innovative or not.

Patent injunction rights may or may not be socially desirable, depending on the specifics of the situation. On one hand, we want to reward innovation with limited exclusivity rights; after all, that’s the whole point of the patent system. On the other hand, we may want to limit injunction rights for overlapping patents if such rights overcompensate the patent holder with unreasonable exclusivity periods. Whether injunctions should be awarded may be less subject to universal standards and should be evaluated on a case-by-case evaluation, which, to some degree, is already the approach taken by courts in evaluating issues of irreparable harm, balance of hardships, and public interest.78

On damages remedies, the type and amount of damages that can be awarded also impacts the long-run success of the economic system. Over the past decade, courts have placed considerable ongoing emphasis on proper patent damages through the concept of apportionment—i.e., aligning the damages remedy to the economic footprint of the innovation.79 From an economic standpoint, the better we can align damages remedies with the economic value of the innovations that are occurring, the better the economic incentives will flow back into the real economy into R&D and innovation decisions. The Federal Circuit appeals court for patent cases has had damages remedies via lost profits and reasonable royalties top of mind in aligning public policy considerations over the past decade and appears to have achieved more consistency in that regard in recent years.

Considering both remedies, there may be some balance between them that is better than currently being allowed. Injunction rights may be warranted up to a point, and then allowing competition and reasonable compensation for the patent owner thereafter may make more sense. Yet, all things considered, this is already how the current system works, and, despite challenges, substantial revision may not be needed.

[3] Limit product exclusivity terms. A third policy approach might be to limit product exclusivity terms directly in some way, beyond unexamined enforcement of patent duration. As discussed, the Patent Act of 1790 originally included a duration of 14 years for patent term, and the term has fluctuated from 14 to 21 years since then, with current duration at 20 years from earliest filing date.80 However, in some circumstances described above, companies have enjoyed product exclusivity for more than 30 years from launch, potentially 40 years or more from original conception. Perhaps that duration represents a justly earned consequence of subsequent inventions, or, as discussed, perhaps there are systems and incentives in place that cause the unintended consequence of duration to be too long.

One way to curb excesses of product duration would be to regulate limits on it directly — in other words, allowing new pharmaceutical products to earn exclusive rights

[Page 152]

granted by FDA or Congressional law as opposed to the patent system. Determining or limiting exclusivity based on product life rather than the patent conception could have several advantages: (1) guaranteeing innovators a certain duration of exclusivity regardless of invention timing, (2) reducing incentives to improperly extend the duration of exclusivity, (3) reducing the need to rush through FDA approval to achieve as long an exclusivity period as possible, and (4) putting a limit as to how long monopoly profits can be collected before the benefit of competition kicks in. On the other hand, designing new duration laws may add unnecessary complexity to a system that is already designed to balance rewards and competition. On net, similar to the targeted legislation described in the market-based strategies, imposing some limits to product exclusivity seems like a policy path with potential for success.

[4] Variable patent term length. A fourth way to tackle duration would be to allow for variable patent lengths for different industries or degrees of innovation. One can imagine a system where original patent protection has a longer duration, and follow-on innovations may add duration in smaller increments, which would apply to multiple patents on the same product. In other words, additional patents may increase exclusivity rights of a product, but to a lesser degree as the innovations become more incremental. In theory, this could be implemented by granting the USPTO discretion of patent length on a sliding scale based on evaluation of multiple factors, for example: (a) the degree of innovation, (b) existing patents on the same product, (c) the impact on competition, and others. Such a sliding scale may better align the economic value of the innovation with the patent duration that is awarded.

With this approach, the details matter a lot. On the one hand, a flexible and discretionary system could be implemented, which would allow for individual assessment of the patent issuance circumstances but may be less clear and predictable for those seeking patents. On the other hand, a more defined yet tiered system could be implemented, which would allow for some variation in patent length but still provide clear rules and instruction for which circumstances warrant longer or shorter durations. Either way, any sort of policy proposal in this regard should provide proper guidelines so that experienced examiners and attorneys have clarity and consistency of when patent terms may be awarded for longer or shorter durations. All that said, the authors recognize the appeal of simplicity of the current system, where all patents receive the same term. Further analysis and research may be warranted to determine the best structure for a variable patent term length.

D. Summary

Whatever the mechanism, the policy concern seems to be that some products have exclusivity for too long. From a policy perspective, focusing on the duration of product exclusivity may be the best path forward, at least in the pharmaceutical industry where the process of generic competition is well defined, since this represents the most tangible unintended consequence and causes us to rethink whether we have gotten the public policy trade-off correct. Naturally, no system is perfect, and each will have its own costs, benefits, and distortions. In the end, the goal is to pick the system that works aligns incentives and rewards innovation sufficiently but not indefinitely.

In the view of the authors, the viability of potential policy based on the discussion above can be summarized as follows:

[Page 153]

Table 1. Summary of Public Policy Approaches

| Policy Approach | Assessment |

| Market-based strategies | |

| (e.g., product hopping and reverse payments) | |

| [1] Continue current enforcement efforts | Helpful, but nearing limits |

| [2] Improve antitrust enforcement | Potential for improvement |

| [3] Legislate targeted extensions to enforcement | Promising path forward |

| Patent-based strategies | |

| (e.g., patent thickets and evergreening) | |

| [1] Improve patent issuance at the USPTO | Potential for improvement |

| [2] Focus on patent infringement remedies | Helpful, but nearing limits |

| [3] Limit product exclusivity terms | Promising path forward |

| [4] Variable patent term length | Potential for improvement |

Whatever the approach, further assessing the length of duration has clear public interest. In 2019, a bipartisan bill was introduced to the Senate to "tackle the pharmaceutical industry’s practice of gaming the patent system to extend monopolies on lifesaving drugs."81 The Reforming Evergreening and Manipulation that Extends Drug Years Act (REMEDY) included provisions to (1) amend the "FDA statute to remove incentives for drug manufacturers to file excessive patents," (2) "lift onerous legal barriers that delay generic market entry" and (3) "increase[] transparency and remove[] hurdles for generic drug companies by ensuring that when a patent is invalidated by a ruling at the [USPTO], and upheld on appeal, the FDA’s listing of relevant drug patents would be updated."82 Policy has yet to be finalized, though future legislation proposals seem likely as we continue to find the best approaches for improvement.

V. CONCLUSION

For public policy, deciding what matters most and what will work best usually involves going back to first principles of what the system is designed to achieve. At the core, the patent system was put into place to solve an economic externality, based on the belief that individual rewards to innovation are not as large as societal benefits of innovation, such that innovation would be undersupplied in a purely laissez-faire economy. By granting patent rights to those who develop innovations, we incentivize individuals to share and bring to market innovations that otherwise may not have been developed.

Though, of course, it is not only the existence of a solution (i.e., the rights themselves) but the degree to which they are implemented (i.e., the strength and duration of those rights). For patents, we focus on the resulting length of product exclusivity as a basic observable measure for how well the patent system is working. Too short a duration, and innovation

[Page 154]

is not sufficiently rewarded. Too long a duration, and innovation is overrewarded at the expense of consumers.

The pharmaceutical industry has historically been a shining example of the patent system working well, encouraging billions of dollars of research and development towards modern medicines that we all value. But lately, with the amount of money being made and the length of market exclusivity for some products at the extremes, courts and lawmakers have become concerned that the trade-off towards protection has gone too far. As a result, several methods are seeking to curb the most extreme unintended consequences, antitrust policy and enforcement being one of them.

In the view of the authors, antitrust enforcement on patent issues in pharmaceuticals does not need major revision. Core principles of preventing anticompetitive conduct are alive and well, in the pharmaceutical industry and otherwise, and provide reasonable limits to restraints on competition. Accordingly, we should continue to embrace the limits of market-based strategies insofar as they violate historical tenets of antitrust law. Indeed, many of the boundaries may already have been tested over the last 10 to 15 years, leaving us with successful enforcement in some areas and less successful enforcement in others. In that regard, there appear to be certain unintended economic consequences where patent protection goes too far and cannot be fixed by current antitrust law. In those cases, we may benefit from targeted policy that puts limits on product exclusivity that will otherwise persist with the current system.

This is the age-old balancing act between two competing objectives, so that the broader society can benefit from individuals pursuing self-interest (by rewarding innovation) and collective benefit that comes from market systems (by allowing competition). In cases where the reward and protection seem "too long," we want to think about mechanisms that can simply and reasonably move the trade-off back towards the optimum, without losing what is already working well. Our market economy works best when rules are clear, incentives are aligned, and companies are rewarded for creating economic value. And that is an objective on which we can all be aligned.

[Page 155]

——–