Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Spring 2016, Vol 25, No. 1

Content

- 2015: a Year of Big Plaintiff Wins In Antitrust and Privacy Cases

- Big Stakes Antitrust Trials: O'Bannonvnational Collegiate Athletic Association

- California Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law Update: Procedural Law

- California Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law Update: Substantive Law

- Chair's Column

- Considerations, Not Limitations: An Argument Against Defining the Anticompetitive Harm Under F. T.C. Vactavis As the "Elimination of the Risk of Potential Competition"

- Editor's Note

- Ftc Data Security Enforcement: Analyzing the Past, Present, and Future

- Golden State Institute 25Th Anniversary Retrospective and Prospective Views On California Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

- Keynote Address: a Conversation With the Honorable Tani Cantil-sakauye, Chief Justice of California

- Managing Antitrust and Complex Business Trials-a View From the Bench

- Masthead

- Royal Printing and the Ftaia

- Settlement Negotiation Tactics, Considerations and Settlement Agreement Provisions In Antitrust and Ucl Cases: a Roundtable

- The Decision of the Supreme People's Court In Qihoo Vtencent and the Rule of Law In China: Seeking Truth From Facts

- The Ucl-now a Money Back Guarantee?

- The Nexium Trial Pioneers Actavis' Activation: a Roundtable of Nexiums Counsel Reflect On Their Six-week Trial

THE NEXIUM TRIAL PIONEERS ACTAVIS’ ACTIVATION: A ROUNDTABLE OF NEXIUMS COUNSEL REFLECT ON THEIR SIX-WEEK TRIAL

By Moderator and Editor: Cheryl Lee Johnson;1 Panelists: Kristen Johnson, Steve Shadowen, John Schmidtlein, and Doug Baldridge

I. BACKGROUND

A. The Reverse Payment Agreement Issue and the F.T.C. v. Actavis Decision

1. The Rise of Reverse Payments and Developments in Federal Law on Reverse Payments Pre-Actavis2

Robust generic competition to a branded drug significantly reduces drug prices for the consumer.3 However, generic competition can be delayed by reverse payment agreements under which a branded drug company pays, either in cash or side deal incentives, rival generic companies in exchange for their agreement to delay their competition. These payments are made in the context of settling patent litigation between the brand and generic over the validity and enforceability of the branded company’s patents relating to that drug.4 The resulting settlement can facilitate a combination between pharmaceutical rivals that restricts the output of generic drugs and extends the monopoly pricing of the branded drug’s sales by avoiding the legal challenge to the patents that might end that monopoly.5

Before 2006, drug manufacturers generally considered these agreements unlawful, and settled their patent lawsuits based in principle upon the perceived strength of the patent in question.6 These agreements generally did not raise antitrust concerns, as they were not drawn to preserve the patent-holder’s monopoly nor paid for by sharing monopoly profits between the two competitors.7

[Pgae 109]

However, a body of law developed in which these agreements were increasingly insulated from legal challenge, culminating in the Second Circuit’s decision in In re Tamoxifen Citrate Antitrust Litigation.8 Under this precedent, the agreements were subject to antitrust scrutiny only with evidence that the underlying patent was procured by fraud or that the branded company’s patent litigation was a "sham."9 Ironically, this standard became known as the "scope of the patent" test, though it effectively foreclosed inquiry into the scope, validity, or enforceability of the patent except in very limited exceptions.10 In the wake of the institution of this permissive standard came a surge of these agreements, with many, if not most, adopting highly-disguised forms given lingering concerns about their ultimate legality.11 Introducing payments12 into the settlement process raises antitrust concerns as the payment provides an incentive for resolving the patent litigation beyond the perceived strength of the patent. This skews the decision of the generic firm of when to enter the market and induces the generic firm to accept a later date to enter competition than would be accepted without the payment. Many reverse payment agreements offer generics greater value than that available from successful competition with the branded drug.13 Conversely, these agreements enable the branded company to buy a greater degree of market exclusion and monopoly than it could get based upon the strength of its patent alone.

[Page 110]

Erosion of the virtual antitrust immunity these agreements enjoyed under the Tamoxifen standard was slow, though the standard was arguably at odds with the law in some courts, and denounced by the Federal Trade Commission ("FTC"), Solicitor General, academics, regulators, and even some of the judges that decided Tamoxifen.14 Prior to the Supreme Court’s ruling in F.T.C. v. Actavis, the federal courts—with the exception of the Third Circuit in In re K-Dur Antitrust Litigation15—largely continued to embrace the criticized Tamoxifen standard.16

2. The Supreme Court’s Decision in F.T.C. v. Actavis

Having rejected certiorari in six previous reverse payment agreement challenges,17 the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari in the Eleventh Circuit decision in F.T.C. v. Watson18 that had also followed the controversial Tamoxifen decision. Two months after the Eleventh Circuit’s Watson decision, the Third Circuit in In re K-Dur rejected Tamoxifen as "bad policy" that neglected the broad public interests in freeing competition from price-fixing agreements stemming from narrow or invalid patents.19 Rather, K-Dur concluded that reverse payments should be considered presumptively unlawful as they "permit the sharing of monopoly rents between would-be competitors without any assurance that the underlying patent is valid."20

The split was resolved by a five-to-three United States Supreme Court decision in F.T.C. v. Actavis, which rejected Tamoxifen as an erroneous interpretation of federal antitrust and patent law.21 The Court found that reverse payment agreements could be anticompetitive and that their presumptive immunity from antitrust under Tamoxifen’s "scope of the patent" test could not be justified under either patent or antitrust law.22

[Page 111]

Examining the extent to which patent law protected these agreements, the Supreme Court concluded that patent law provided no support for patentees to pay their drug company rivals to stay out of their markets.23 Rather, the patentee’s statutory rights—"whether expressly or by fair implication"—could not be viewed as extending any right to pay one’s rivals not to compete.24 Both history and experience with these agreements further convinced the Actavis Court that paying one’s rivals was not necessary to settle pharmaceutical patent litigation.25

Similarly, the Court found that the Hatch-Waxman Act did not protect reverse payments; quite to the contrary, it condemned such payments both in its letter and spirit.26 Finally, the Actavis court also declined to justify reverse payment agreements with any pro-settlement policy.27

While Actavis restored antitrust scrutiny of these agreements, it fell short of adopting the approaches urged by the FTC, the states’ attorneys general, and private plaintiffs. They had urged the Court to treat the agreements as per se illegal, presumptively illegal, subject to a quick-look test, or some other variant thereof.28 However, the Court disagreed, ruling that the agreements were to be evaluated under a rule of reason, using "traditional antitrust factors."29 But the Court left it to the trial courts to further flesh out that standard, vaguely instructing trial courts that they can:

[A]void, on the one hand, the use of antitrust theories too abbreviated to permit proper analysis, and, on the other, consideration of every possible fact or theory irrespective of the minimal light it may shed on the basic question—that of the presence of significant unjustified anticompetitive consequences. 30

[Page 112]

Predictably, this "instruction" has generated a surfeit ofcommentary,31 while courts overseeing the bountiful post-Actavis lawsuits struggle to divine the intended boundaries of Actavis.32

B. In Re Nexium Antitrust Litigation

1. The Nexium Reverse Payment Agreements

Nexium, a branded drug manufactured by AstraZeneca ("AZ") whose active ingredient is esomeprazole magnesium, is widely used to treat heart burn, and enjoys annual sales of a billion dollars a year. It was launched to replace AZ’s earlier heart burn medication, Prilosec (which largely has the same active ingredient as Nexium), as it faced the end of its marketing exclusivity. AZ claimed that Nexium sales were entitled to market exclusivity due to several patents related to a process for manufacturing and method for using Nexium.33

However, AZ’s Nexium patent claims were considered by some would-be rivals as dubious, and thus were challenged under the controlling Drug Price Competition and Term Restoration Act of 1984 (known as the "Hatch-Waxman Act").34 Recognizing that questionable patent claims could be used to chill generic competition, Congress adopted the Hatch-Waxman Act for the "express purpose of expediting the entry of non-infringing generic competitors into pharmaceutical drug markets in order to decrease healthcare costs for consumers."35 The Act incentivizes would-be generics to challenge branded drug patents, and provides them a means to certify around the claimed patents36 and seek approval of their generic launches from the Food and Drug Administration ("FDA").

In August 2005, generic manufacturer Ranbaxy applied for FDA approval to launch generic Nexium, certifying that the Nexium patents were either invalid as obvious, or were not infringed. AZ’s responsive suit against Ranbaxy for infringement of the Nexium patents, under the Hatch Waxman Act, automatically stayed any FDA approval of Ranbaxy’s application for thirty months without regard to the merits of the litigation. Subsequently, Teva and DRL, two other generic companies, also sought FDA approval to launch generic Nexium and were sued by AZ.37

[Page 113]

In April 2008 as the thirty-month stay was about to expire, AZ settled with Ranbaxy, the first sued and the first-to-file, with Ranbaxy agreeing to delay a generic version of Nexium until May 27, 201438 and drop its challenge to the patents. In exchange, Ranbaxy received from AZ an agreement not to launch an authorized generic as well as "lucrative manufacturing and distribution agreements and prospective future revenue under an exclusive marketing agreement."39

Because the AZ/Ranbaxy agreement precluded any FDA approvals before the agreed May 27, 2014 date, Teva and DRL sought to uncork this "bottleneck" with their own actions against AZ. However, they, too, settled with AZ by agreeing to delay generic competition until May 27, 2014 unless another generic legally entered the market earlier. 40 In exchange, Teva received AZ’s agreement to drop damage claims for Teva’s at-risk launch of Prilosec, and DRL received a release of damage claims for its generic sales of another drug, Accolate.41

Following these agreements, direct and indirect purchasers of Nexium filed numerous class actions under federal and state laws, challenging the agreements as unlawful restraints on competition for generic Nexium. The Nexium patents were alleged to be invalid, as the European and Canadian patent offices had already held.42 The plaintiffs further contended that in light of the dubious scope of the patents, the size and amount of consideration flowing to the settling generics, and the fact that the generics provided only an agreement not to compete, the agreements were unlawful agreements not to compete.43 But for these agreements, the plaintiffs alleged generic Nexium would have been available by April 2008, and thus would have ended Nexium’s monopoly pricing of Nexium from April 2008 through at least May 27, 2014.44

2. Pretrial, the "Rip-Roaring Six-Week Trial," the Jury Verdict, and the Appeal in Nexium

While the Nexium case was the first post-Actavis case to be tried, the protracted pretrial proceedings consumed several years, and followed what the trial judge, District Court Judge Young in Boston, confessed was his imperfect and changing understanding of the contours of both the case and the dictates of Actavis.45 Along the way, the court dismissed all the plaintiffs’ claims on twelve summary judgments, and then reversed two grants ofjudgment.46 The judge limited the parties to a single theory of liability after concluding that the Ranbaxy agreement could not be a source of competitive injury.47 He also issued a series of rulings limiting the introduction of various expert testimony and FTC studies and bifurcating the trial with the first phase to be the existence of an antitrust violation and the period of delay to commence on October 20, 2014.48

[Page 114]

The first phase trial focused on the Teva agreement and the conspiracy claim. On the seventeenth day of the trial, the court confessed it had a "fairly fundamental misconception" and now understood that the Ranbaxy agreement could create a blocking position and create delay.49 This, the judge further confessed, was his "sockdolager" and he "promptly corrected course," allowing the plaintiffs to proceed on their theory that the Ranbaxy agreement was anticompetitive.50 The defendants, faced in mid-trial with new theories to defend, moved for a mistrial but were rebuffed by the court.51 According to the judge: "Thereafter, the case went swimmingly (in the sense that I understood what the lawyers were doing and why)."52

The trial concluded on December 2, 2014 with the jury returning its findings that (1) AZ exercised market power within the relevant market, (2) the settlement of the AZ-Ranbaxy patent litigation included a large and unjustified payment by AZ to Ranbaxy, and (3) AZ’s Nexium settlement with Ranbaxy was unreasonably anticompetitive, i.e. the anticompetitive effects of that settlement outweighed any procompetitive justifications.53 Despite being convinced that the anticompetitive efects of the AZ-Ranbaxy agreement outweighed any procompetitive benefits, the jury answered "no" to Jury Question Number Four, which read, "Had it not been for the unreasonably anticompetitive settlement, would AstraZeneca have agreed with Ranbaxy that Ranbaxy might launch a generic version ofNexium before May 27, 2014?"54 By answering "no" to that question, the jury could not conclude that Ranbaxy would have agreed to a new earlier date of entry, and while there may have been the "intent to violate the antitrust laws" the jury could not establish that the agreement caused delay and overcharges.55

The direct purchasers and the end-payors timely moved for a new trial, which was denied on August 7, 2015 in a lengthy memorandum opinion opening with the court’s telling summation: "I did not try the case very well. I did try it fairly."56 Following entry of final judgment for the defendants, the plaintiffs filed an appeal with the First Circuit, which appeal is currently being briefed by the parties.57

[Page 115]

II. PANEL INTRODUCTION

On this panel, we are honored to have the lead trial team from the six-week Nexium trial in Massachusetts. Nexium, the purple pill used by Larry the Cable Guy and millions of other Americans suffering heartburn, has annual United States sales of almost a billion dollars.

Some ten years ago, several drug companies sought to sell generic versions of Nexium and were sued by Nexium’s manufacturer, AstraZeneca for patent infringement. The patent suits were settled with the parties agreeing that they would not compete for any Nexium sales before May 2014, and Ranbaxy, the first-filing generic company, was alleged by plaintiffs to have received valuable side agreements and promises.

These agreements are fairly typical of the hundreds of reverse payment agreements executed over the last few years. In 2013, the United States Supreme Court in the landmark ruling in F.T.C. v. Actavis held that these agreements could be anticompetitive, and were to be evaluated under a rule of reason. Beyond that, as you will see, there is little agreement between the litigants as to what the Supreme Court meant or said in Actavis.

In Nexium, add to this a judge trying to figure out the issues at the intersection of antitrust, patent, and the Hatch-Waxman regimes, in the first case to go to trial post-Actavis. Not until the parties were seventeen days into the trial, did the judge, by his own account, have his "sockdolager," or "aha moment," as to what the case involved, and changed his directions to counsel. A mistrial motion was denied and the case continued for several more weeks. The jury found that there was a "large and unjustified payment" by AstraZeneca to Ranbaxy that was "unreasonably anticompetitive," but that there was no harm caused by the agreement. The matter is on appeal, and the appeal is of-limits for this discussion.

Now let me introduce our illustrious trial panel.

- Representing the direct purchasing class action plaintiffs is Kristen Johnson, a partner at Hagens, Berman, Sobol and Shapiro; she was a key member of the plaintif’s Nexium trial team as well as the Neurontin trial team that secured a $142 million judgment against Pfizer for off-label marketing. She is also the lead on numerous other key pharma class actions.

- Also for plaintifs is Steve Shadowen, founding partner of Hilliard and Shadowen; he has secured some of the key pay-for-delay rulings, including those in K-Dur and Cardizem. He has tried too many significant antitrust cases to list, and received the American Antitrust Institute award for "Outstanding Antitrust Litigation Achievement in Private Practice."

- Representing AstraZeneca is John Schmidtlein, co-Chair of Williams and Connolly’s Antitrust Practice; he has been lead trial counsel in numerous class action suits, and represented Google, Archer Daniels Midland, and many pharma and pharmacy benefit managers in high profile government investigations, and also represented the states against Microsoft.

- Representing Ranbaxy, the generic, is Doug Baldridge, Chair ofVenable’s litigation group; he has tried numerous complex antitrust and other cases to verdict, and while he loves a good trial, he is also devoted to social justice cases, including a suit for blind voters in Florida. In February, he will be trying Provigil, the second post-Actavis case to go to trial.58

[Page 116]

III. DISCUSSION

Moderator: First, we will ask each side to take three minutes to briefly discuss its strategy or the major themes it sought to establish at trial, starting with the plaintiffs.

Shadowen: It took me seventeen days to explain all this to JudgeYoung, so I will try to do it for you in a little less than that. The major themes for the plaintiffs were this:

- That AstraZeneca’s patents on Nexium were weak. We never intended to prove that they were invalid or not infringed; rather that the patents were weak and subject to a signiicant challenge.

- Secondly, in light of the weakness of the patents, that AstraZeneca had a risk of losing the patent litigation, and, therefore, having generic competition to Nexium launched.

- Thirdly, to avoid that risk of competition, that AstraZeneca made a payoff to Ranbaxy and others to withdraw their challenges to the patent and to delay entry into the market.

- So far, we have weak patents, a risk of loss of the litigation and competition, and a payoff to avoid that risk.

- Lastly, absent the payoff, that, in fact, there would have been generic entry into the market sooner than was.

Key for us was not to take on more of a burden than we thought that we legitimately had under the law. We didn’t want to prove that the patents were invalid or not infringed, just that they were weak. We didn’t want to have to prove that because we didn’t think we had to prove it under the law. We did not need to show that absent the payment, that the generics would have won the litigation, just that there was a risk of AstraZeneca losing. So part of the delicate balancing act for the plaintiffs was not taking on more of a burden than we thought we legitimately had under the law. I think overall we were fairly successful on that. Obviously, in terms of the jury’s verdict, which was on special interrogatories, we lost on a causation question.

The plaintiffs believe those causation issues are the result of errors made by Judge Young at trial, that are now the subject of appeal, so we are not going to talk about those today. But that’s sort of in a nutshell, the big picture, from where we saw the case.

Moderator: Now, the defense high level strategy.

Schmidtlein: I am going to address a number of the issues from the defense perspective.

[Page 117]

Just to be clear here, everything I am saying here it can be found by searching through the openings, closings, and some of the other transcripts from the trial. We obviously had a very different view of the patents from that of the plaintiffs, and we will talk a little bit about that later in the panel.

In this case what you had was a license entry date that was tied to the expiration of the key compound patents for AstraZeneca. Our position was that those patents were very, very strong. There were other patents we also thought were strong that went out further than the license entry date. But one of the key issues for AstraZeneca was demonstrating that, absent a settlement agreement here, we weren’t going to give an earlier entry date. And the evidence in the case and the settlement discussions that took place were consistent with that. So one of our key issues and themes was that we had very strong patents. We were going to win the patent case at least as to those patents, if not other patents, that would go and keep the generics out longer.

So, therefore, the settlement agreement provided for early entry, in our view. In other words, there were patents covering Nexium that extended much longer than the license entry date. And we think that bolstered both an antitrust competition angle and also a causation angle.

There also was in this case an extraordinary amount of evidence regarding causation in the FDA approval context. This case was fraught with, as Doug can attest to, this case had some very, very difficult causation issues for the plaintiffs. By the time this case had come to trial, the license entry date had already come and gone through the settlements. The license entry date was May of 2014. We tried this case from October until December of 2014. And at the time of the trial, none of the generics who had settled had obtained inal FDA approval. Indeed, the key generic, the only generic that the judge was focused on in terms of would they have gotten to market, had not even obtained tentative approval as of the date of the trial. So this was a very, very signiicant causation issue that the defense pressed very hard on at trial.

There was another sort of tricky issue for purposes of this case. Because the judge found that Ranbaxy, the first filer, could never have come to market, the plaintiffs were pursuing a theory whereby they had to demonstrate that somehow Ranbaxy would have waived their irst iler exclusivity to Teva, the second generic who had settled. We also believed we had very, very strong arguments that there was no evidence of that, that they could not demonstrate not only that they had to get approval, but that somehow Ranbaxy would have gotten out of the way and allowed Teva to come to the market earlier than them.

Baldridge: Briefly, Cheryl noted, there was the—I can’t pronounce the word (sockdolager)—the moment of truth in the seventeen days of trial. So our feeling during the first seventeen days of trial is, "Why the hell are we here?" We did the Admiral Stockdale-Ross Perot, "We can’t figure out why we’re here." And Judge Young says, "You are here seventeen days in the trial because I have now decided your agreement with AstraZeneca is the focus" So we had to shift on the fly, and we really went full-in causation. And I don’t need to repeat what John said, but there are enormous issues with plaintiff’s case on causation, with FDA approval and Ranbaxy’s ability to launch. The but-for fantasy world set up by the plaintiffs simply had no factual support for it. It was, in my view, a fantasy.

[Page 118]

Moderator: We will get to that later when we talk about causation. I think at this point, we are now going to proceed to a kind of a "mini trial" on one of the key liability issues in this case, and that is—was there a "large and unjustified" payment from AstraZeneca to Ranbaxy in exchange for their agreement to delay competition? We are giving each side nine minutes to give you their best evidence and arguments to show you the enormous complexity of this key issue.

Shadowen: So, as you all know, one of the problems with a highly complex antitrust trial or commercial litigation of any kind, is how do you take all this complexity and boil it down, and teach it to a jury of eight people pulled off the streets of Boston? I am going to show you at least how we tried to do it in this trial.

We wanted to show that an agreement is anticompetitive under the antitrust laws if it results in less competition that would have resulted absent the agreement. To understand why the plaintiffs are here telling you that there’s an antitrust violation, you need to understand four concepts, and here they are: Reduced competition, the expected outcome of patent litigation, pay-for-delay, and a large payment. I am going to walk you through very quickly each of those four key concepts.

[Page 119]

Four Key Concepts

- Reduced Competition

- "Expected" Outcome

- Pay for Delay

- Large Payment

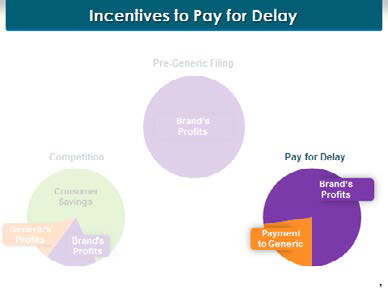

Let’s start with reduced competition. When AstraZeneca is the only manufacturer of this product on the market, it has one-hundred percent of all the profits flowing from the sales of Nexium. Last thing in the world it wants is a generic manufacturer to come into the market, because when a generic comes into the market, this is what happens: All those brand proits from Nexium sales decrease to about a quarter of where they were before, because some people will still buy the brand product even when the generic is available. The generics come into the market and they take a little bit of the proits, but not a lot of the proits. This is because there’s not just one generic on the market after a period of time, there are three or four, and they compete like cats and dogs. And with this generic competition, the price goes way down, as we all know, that’s what causes generic prices to be so affordable for all of us.

What happened to the rest of those profits that AstraZeneca had when it was the only player in the market?

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 120]

They are here in the green—in the form of savings to consumers. The consumers, you and I, get all those savings that used to go into AstraZeneca’s pockets. Now, when you look at this chart, if you were a generic manufacturer or a brand manufacturer, a light might come on in your head and say, "Gee, we are competing with each other, and there are all these profits that were available before that are going to consumers. Here’s an idea—why don’t we cut out the consumers and split those consumer profits between ourselves?"

And that’s the point of the pay-for-delay payment. The brand manufacturer says to the generic, "Let’s not compete with one another. I will pay you some of my profits directly. We’ll share the part that would have gone to consumers and share it between ourselves." And that’s, in essence, reduced competition, the elimination of competition in order for the brand and the generic to share those consumer savings that should have gone to you and me, to share them between ourselves.

But, you may say, "Wasn’t there patent litigation and what happened if the generic had lost the patent litigation? There wouldn’t be any competition then. There’s no guarantee that the generic would have won the underlying patent litigation." That’s where the economic concept of expected outcome of litigation comes into play.

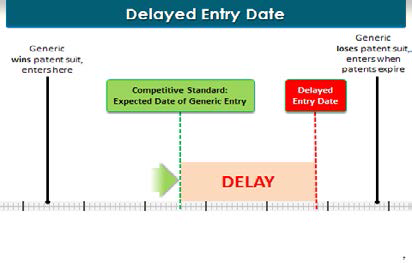

Image description added by Fastcase.

What’s the expected outcome? It is the probability-adjusted outcome—what’s the chances that that would happen. This is a timeline with the beginning of the patent litigation here on the left, going over to the end of the patent term on the right. Without a payment, here’s what would happen in the litigation, one of two things: either the generic would win the patent litigation and enter the market way over here on the left, or the generic would lose the patent litigation and generic entry wouldn’t occur until the end of the patent term, way over here on the right. But economists have a concept that says "What’s the expected date of entry?" The expected date of entry is the probability-adjusted entry. One way to think of it is: without any payments or payoffs of any kind from the brand manufacturer to the generic manufacturer, what’s the date they would have agreed on as a compromise? They are both highly intelligent. They have all the information about the underlying litigation. They know the chances of winning and losing. And the compromise date that they would agree upon is what’s called the expected date of generic entry.

[Page 121]

Why is the date of expected generic entry important? Because it ties into our concept of paying for delay. Delay compared to what? Delay compared to the date of expected entry. That’s what happens here. So let’s take ourselves back in time to AstraZeneca and Ranbaxy in a room negotiating without any payments between them. This is hypothetical, they would have agreed on a date that is here marked by our green line. That’s without a payment.

But then AstraZeneca says, "Hey, wait a minute. Rather than you entering on that date and making your profits by selling generic Nexium, why don’t I give you a payment?" As my co-counsel will explain, this payment was on the order of magnitude of a billion dollars. "I’ll pay you a billion dollars, and we’ll move that date, the entry date from the date of expected outcome, the date we would have agreed upon without a payment, way over here to the right." And that’s the delayed entry date. That’s pay-for-delay.

By the way, this same concept works in reverse. If you see that there’s an agreed entry date between the brand manufacturer and the generic manufacturer, and you see that there was a payment from the brand manufacturer to the generic manufacturer, you know that the expected date of entry was further over to the left. Otherwise, why is the brand paying the generic? There’s no reason to pay the generic unless the brand manufacturer is getting something in return. The something that AstraZeneca got in return was the movement of this entry date from the left-hand side over to the right.

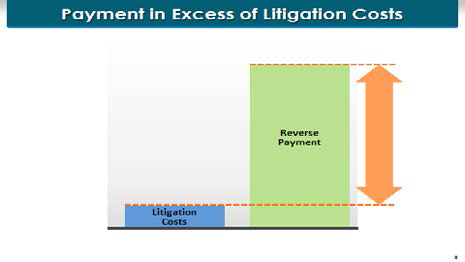

What’s a "large" payment? Judge Young is going to instruct you that a large payment is a payment in excess of the saved litigation costs. And we can illustrate that very easily.

Image description added by Fastcase.

The payment here was on the order of magnitude of a billion dollars. The testimony is going to be that the litigation costs that AstraZeneca saved by settling the litigation were on the order of magnitude of $10 to $15 million. So it is very clear that these—the payment here was far in excess of the saved litigation costs.

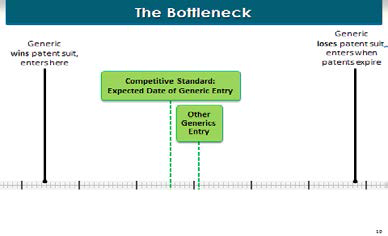

One final concept I want to go over very quickly, and that’s what we call the bottleneck.

[Page 122]

Image description added by Fastcase.

Ranbaxy was the first generic manufacturer to challenge these patents. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, the first manufacturer to file its application with the FDA for approval to sell the generic—which was Ranbaxy in this case—is entitled to one-hundred eighty days of market exclusivity, as the only generic manufacturer on the market. The FDA cannot approve any other generic manufacturer to come into the market until Ranbaxy has been in the market for one-hundred eighty days.

So here’s the problem: Here’s our competitive entry, in the middle of the time frame, one-hundred eighty days later, we can expect all kinds of other generic manufacturers to enter the market. But when AstraZeneca makes that enormous payment to Ranbaxy to get Ranbaxy to move its entry date over to the right, as a matter of law, by the Hatch-Waxman Act, the others cannot enter for one-hundred eighty days later. So that payoff from AstraZeneca to Ranbaxy had the effect of not only moving Ranbaxy’s entry date, but all the other manufacturers to the way end of the right.

K. Johnson: So let’s talk about the evidence of the payment from AstraZeneca to Ranbaxy, and let’s be concrete about it.

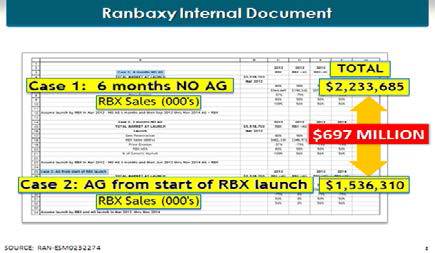

We learned in the summer of 2007 that AstraZeneca and Ranbaxy sat down and had a settlement conference. And what did the parties do afterwards? Ranbaxy goes back to its offices and starts modeling how much additional money it will make if AstraZeneca agrees not to compete with Ranbaxy during its one-hundred eighty day exclusivity period, which AstraZeneca could do by launching an authorized generic ("AG") in that period. And Ranbaxy calculates that it will make an additional $679 million as a result of AstraZeneca’s agreement not to compete in that one-hundred eighty day period.

[Page 123]

Image description added by Fastcase.

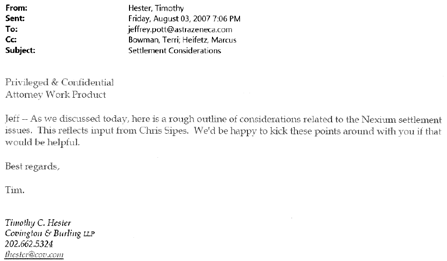

What does AstraZeneca do after this? AstraZeneca goes back to its offices. And its outside lawyer, Mr. Hester, the chairman of Covington & Burling, sends a note to AstraZeneca’s inside counsel, Mr. Pott, that says we think we can get a "relatively late entry date" if we agree not to compete with an authorized generic. A "relatively late entry date."59

Nexium Settlement Considerations

- Ranbaxy has recently settled a number of Hatch-Waxman cases and appears to be interested in settling rather than litigating such cases.

- Ranbaxy likely will want a settlement that preserves its 180-day period of exclusivity against other generics and also guarantees that exclusivity against authorized generic competition, and it may be willing to agree to a relatively late entry date in a settlement that provide generics may limit AZ’s ability to settle with other ANDA applicants,the benefits of settlement with Ranbaxy may more than overcome that disadvantage.

So AstraZeneca’s lawyers now tell you, the jury, because you are the jury today, this is an "early entry date," before the expiration of all the patents. But have they shown you one document or elicited testimony that says it was an early entry date? We don’t have that. We have one contemporaneous document that says, this is a "relatively late entry date."

So why is this a large and unjustified payment? First, it is large because it gave $679 million in value to Ranbaxy; Ranbaxy’s internal employee calculated it was worth at least $300 million. We know it was going to cost AstraZeneca, in terms of lost sales, about $500 million. And we also know, that this amount is significantly higher than the $10 to $15 million in attorneys’ costs that AstraZeneca estimated it was saving by settling this litigation.

[Page 124]

Finally, there were three different deals in addition to the no-AG promise that provided value to Ranbaxy.

AstraZeneca-Ranbaxy Agreement

Ranbaxy

v No-AG commitment $697 million

v Deal to make Nexium API

v Deal to make Nexium product.

v Two distribution deals at 2X profit

v Coordinated entry

AstraZeneca

v Years of first filer delay

v Bottleneck for other generics

v Over $8.8 billion net sales

v Coordinated entry

Ranbaxy went from being a would-be competitor of AstraZeneca to being a partner with AstraZeneca in making Nexium. Ranbaxy was paid money to manufacture Nexium active pharmaceutical ingredient ("API") as well as to literally make Nexium capsules for AstraZeneca themselves. Secondly, Ranbaxy was paid by AstraZeneca to sell Prilosec and Plendil. And we know Ranbaxy internally thought they got a good deal there, because rather than providing the ten percent profit—which is the industry average—Ranbaxy got a twenty percent profit on the API agreement with AstraZeneca. So they got twice the profits out of that deal alone.

So between these side deals and the promise of no authorized generic competition, this was a massively organized and negotiated settlement that was intended to take value from AstraZeneca and move it to Ranbaxy in order to push generic entry off by many years, just what Judge Young told you the law prohibits.

Moderator: And now we will hear the defense perspective on whether the agreements included a "large and unjustified"payment.

Schmidtlein: Everything they said is wrong. I am going to talk about the alleged large and unjustified payment. I am not going to address everything that Steve said, but I am going to talk about the payment. So the alleged payment was three things supposedly, and Kristen was talking about those: The authorized generic distribution agreement, an API and tolling agreement, and what we refer to as the exclusive license, or what the plaintiffs refer to as the no-authorized generic agreement.

[Page 125]

Now, with respect to the authorized generic distribution agreement, this is an agreement. It is not unusual. In some instances you’ll have a situation where a branded company will license a generic to distribute its own branded capsules as a generic. The deal here was an eighty-twenty profit split, AstraZeneca kept eighty percent, and Ranbaxy got twenty percent. The testimony at trial was that Ranbaxy had done agreements that went from fifty-fifty up to ninety-ten. AstraZeneca had done agreements that range from ninety-ten to sixty-forty. There was no expert testimony. Nobody was brought in on the plaintiff’s side to say, "I have studied this industry, I have concluded that eighty-twenty is an unreasonable, non-fair-market-value deal," and I emphasize the words "fair value." You probably remember those words from the Actavis decision, because if deals were of fair value, it is not a payment. So from our perspective, there was no way this authorized generic distribution agreement was going to ever be a large payment.

Second, as to the API supply and tolling agreements that were introduced at trial, it was the same story. There was no expert testimony from the plaintiffs, nobody stood up and said, "The price that AstraZeneca paid to Ranbaxy for either the API or for the finished capsules was not a market price." You remember the allegations in Actavis were that the marketing deals were sort of bogus deals, that in that case, the brand company was paying exorbitant fees and getting very, very little in the way of actual services from the generic company. No testimony to that effect in this case. The testimony was the deals were negotiated at arm’s length. They were negotiated over a long period of time between the business executives who were experts in these areas. They went back and forth, back and forth. They settled on a price that was either at or lower than the price that AstraZeneca was currently paying and consistent with an outsourcing strategy that AstraZeneca had employed.

So, again, were these agreements for fair value? We obviously said absolutely they were for fair value and, therefore, they should be immune from attack under Actavis.

As to the exclusive license or no-AG agreement. Kristen made note of the fact of some internal Ranbaxy documents that purported to estimate what the value to Ranbaxy would have been. I would submit to you that under Actavis, you have to look at this not from the perspective of the generic, but from the perspective of the branded company. Because the whole point of Actavis was: Can you glean something from this payment to tell you something about the strength or weaknesses of the patents? What did the brand think about the strength or weakness of the patents? The testimony in this case was AstraZeneca had done authorized generic—or done a "no-AG deal"—once in its entire history before this settlement provision. It had been in a slightly different factual situation that made it different. But without getting into those details, it was a disaster for AstraZeneca.

AstraZeneca had entered into a situation where it was just a complete mess, and what happened was the CEO of the company was very, very strongly against authorized generic types of deals. AstraZeneca had introduced its own authorized generics, but the generic companies actually had their products pulled from the market, and so AstraZeneca was actually left with its own generic in the market by itself, taking sales away from the brand. So the CEO is like, "I’m not a big fan of these authorized generic deals."

The other factor was that this type of a product was not a good candidate for an authorized generic during the exclusive license which was for one-hundred-eighty days. It was only during the one-hundred eighty-day exclusivity period that AstraZeneca agreed to give the exclusive license. As some of you may remember during the wars on generic drugs, there were actually generic manufacturers who were complaining, threatening litigation and going to Congress and saying, "When these branded companies launch authorized generics during the one-hundred-eighty-day period, that’s dirty pool. That’s undermining the Hatch-Waxman Act. We are supposed to get the one-hundred-eighty days of generic sales. What are these branded companies doing, launching authorized generics?"

[Page 126]

They went to Capitol Hill, the FTC, they complained to everybody.

The testimony we submitted in the case was that AstraZeneca wasn’t going to launch an authorized generic during the six-month period that would increase the erosion of the sales of the brand. While that would have made AstraZeneca a little bit of money, it would have caused AstraZeneca to lose a lot more money in its branded sales. So in the end this "no-AG deal" was worth zero or next to zero to AstraZeneca, and when combined with the fact that they were going to insist upon an entry date of 2014 with the patents, it really had no impact. And Steve’s argument that in the absence of this, AstraZeneca would have moved that license date back earlier, wasn’t going to happen.

Baldridge: I have the unenviable task of trying to cram a closing after eight weeks of trial into, what, three minutes? Here we go, here’s an attempt to truncate.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, we thank you for your patience. We thank you for your patience because we have wasted a large part of your last forty days in this trial. This isn’t about cross-elasticity of demand, not about probability-adjusted outcomes, and it is not about imaginary predictions of what might have happened in a fantasy world where there was no agreement. Because in this case, the real world answers every question you need to answer to decide this case.

The question, as counsel has already posed to you, is whether AstraZeneca made a large and unjustified payment to my client, Ranbaxy, that caused a delay in Ranbaxy entering the market with a generic alternative for Nexium. And the answer is clearly no. How do we get to that answer? Well, for those of you who perhaps did time in the United States Marine Corps, you may know the concept of absolute truths. Absolute truths is the clarity provided in chaos, the simple answers that no one disagrees with and concepts that allow you to reach the answer to a more complicated question. And there are five absolute truths in this case that no one disputes and no one will dispute.

The first one is the truth about AstraZeneca’s patent monopoly. It is an undisputable truth that AstraZeneca’s valid and enforceable patent did not expire until 2019. It is a perfectly legal right provided by the United States Constitution and the patent laws to exclude all competition. That’s the real world, not the fantasy world. That was AstraZeneca’s right.

The second absolute truth is the truth about the AstraZeneca-Ranbaxy settlement. That settlement agreement allowed Ranbaxy to enter the market with a generic alternative on May 27, 2014.You don’t need an economist to do the math and tell you that is five years before expiration of the AstraZeneca patent, which makes me wonder why the plaintiffs’ lawyers call this pay-for-delay. There was no delay. It was early entry. That’s the real world.

Absolute Truth Number Three, the truth about FDA approval. Without final approval from the FDA, every witness has testified that no generic can enter the market. There are thirteen different generic companies that filed to enter the market for Nexium. As of today, none has approval. So as a matter of law, there’s no one who can enter the market with a Nexium alternative. Today, incidentally, the day of this trial, is five months after the early entry date under the AstraZeneca-Ranbaxy settlement agreement, and there still is no generic alternative.

[Page 127]

Absolute Truth Number Four, Hatch-Waxman Act: The bottleneck was given to generics by being the first filers by Congress. That bottleneck status has taken on a bad term with plaintiffs’ lawyers, but, in fact, it was something that is a perfectly legal right created by Congress that is given to the first filer under Hatch-Waxman.

Absolute Truth Number Five, instructed by Judge Young, there was no chance Ranbaxy could enter the market with a generic alternative.

Where does this get us with the existence of a "large and unexplained" payment? Well, you take these five undisputed truths, these absolute truths, and you apply them to the facts of what is a large and unexplained payment.

The first alternative, as counsel has referenced, is the so-called "no-AG" provision. Well, that’s an exclusive license. If Ranbaxy is afforded rights but then can face competition directly from the brand in the form of an AG, that would not be an exclusive license. Exclusive licenses are granted every single day by patent holders, and you will be instructed that an exclusive license, if that’s what you find this is, is perfectly legal, and fully explained this settlement. The second payment would be the so-called side agreements. Well, as counsel has pointed out, there’s not a shred of evidence that Ranbaxy did not do exactly what it was required to do under its agreements in the form of providing API, in the form of distributing the product and that they were paid fair value for those services. There is no evidence to the contrary, and you have been instructed by Judge Young that that’s the case, you must find for defendants.

Moderator: Great. As you see, the issues in these cases are quite complex and these deals are usually structured or negotiated by attorneys. As a result, the deal documents often present a lot of thorny attorney-client privilege issues. You heard Kristen refer to some of the communications to counsel that proved pivotal to the judge’s understanding of the case. So I’d like the plaintiffs to explain their strategy about getting the privileged documents into this case.

K. Johnson: So I am just going to tell you what happened in this case, because I think that’s fascinating and a lesson in itself. In early discovery in the case, plaintiffs asked defendants individually whether they intended to assert an advice of counsel defense. We were told by each no, they were not going to.

We then asked for documents in discovery, we asked questions about their affirmative defenses, and defendants indicated that they intended to assert defenses of reasonableness, of legitimate business justifications, and I am trying to remember the phrasing, but something about merits-based settlement considerations. At the same time, during depositions and in response to discovery requests, defendants lodged attorney-client objections to many requests for evidence relating to their affirmative defenses. As an example, six of the defendants’ deposition witnesses were actually attorneys who had negotiated or worked on the deals, and they were all instructed not to answer questions involving discussions with or communications to clients about the settlement, and that held for the lead settlement negotiators as well.

[Page 128]

So pretrial, it became clear from the pretrial memos that the defendants intended to continue asserting a reasonableness and a business justification defense. You wound up with cross-motions in limine with both the defendants and plaintiffs trying to tee up this issue of attorney-client privilege for the court. The plaintiffs took the position that defendants were improperly using privileges as both a sword and shield, because they prevented plaintiffs from discovering reasons they thought these agreements had legitimate business justifications or satisfied the reasonableness asserted defense, but they continued to maintain those defenses. The defense opposed and asked the court to prevent allowing questions that would draw attorney-client objections. The court did not rule, but he said he was vigorously disposed to prevent the sword/shield issues. But he indicated he would wait and see what actually happened at trial and see how it played out.

At trial, on October 27th and 28th, AstraZeneca’s general counsel, Mr. Pott, testified. A few days later, on the 4th of November, the chairman of Covington & Burling, Mr. Hester, testified. On November 5th, based on Mr. Hester and Mr. Pott’s testimony, plaintiffs filed an emergency motion. Anything that I am stating here is either straight quotations or paraphrased from pleadings already filed. None of this is new. Plaintiffs took the position that Mr. Hester’s testimony about communications with Mr. Pott meant that previously withheld documents should be produced to plaintiffs so we could test the assertions that Mr. Hester had made on the stand. To give a couple examples of questions that defense counsel asked Mr. Hester: "Did you have discussions with Mr. Pott about the Nexium settlement? What did you tell him? Did he provide you any documents?" In that motion, plaintiffs identified twenty-one entries on the privilege log that reflected communications between Mr. Hester and Mr. Pott.

The court ordered the parties to produce those communications in camera. And he reviewed them in chambers and ultimately required AstraZeneca to produce eight documents based on the statements that Mr. Hester and Mr. Pott’s testimony had skirted around the edges of those issues. Once those documents were produced, there were some tantalizing documents as slide three of my earlier presentation.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 129]

It is pretty juicy. In any event, one of those documents ended up being a major part of plaintiffs’ closing statements, certainly the statement that a no-AG promise might get AstraZeneca a relatively late entry date we thought pretty juicy. The jury agreed with us. Following the production of that document, we re-called Mr. Pott and asked Mr. Pott questions about it. Just to give you a sense of the timing on that, Mr. Pott took the stand on day twenty-three of trial, which was December 1st, and the jury was charged two days later, on December 3rd.

Moderator: And now let us learn the defense view on these privilege issues?

Schmidtlein: The privilege issues in these cases are very, very tricky. You are, not surprisingly, going to oftentimes have either in-house or, in some cases, outside lawyers involved in the negotiations of the settlement agreements. So the negotiations themselves are not privileged.

In this case, the defendants were very, very committed to calling those witnesses and laying bare for the jury the process and what happened during the settlement negotiations. We felt like we were going to put those before the jury. We thought the settlement negotiations, actually, and the settlement conference that the judge in the underlying patent case had with some of these same lawyers, was very, very persuasive evidence in defendants’ favor that they were not going to agree and negotiate an earlier settlement date or an earlier license to entry date. So it is impossible not to defend these cases without calling these witnesses. The plaintiffs— candidly, I am not so sure they wanted to hear the answers. They wanted us to invoke privilege in front of the jury. So that’s one of the tough issues you confront. You try to get some direction on that early in the trial. I will say this, though: Most of the questions that purportedly led to the documents were actually questions elicited by plaintiffs’ counsel.

And I would suggest to you, one of the things that is very, very difficult for any lawyer is case law on what’s a privileged communication and what’s a waiver and what’s the scope of the waiver. Once you start researching those issues, you will find as many outcomes as there are cases. The cases are very, very fact-specific, and you are doing this on the fly at trial, making decisions about: Is the answer to that question going to be privileged or not? If I allow the witness to answer it, am I waiving privilege? What’s the scope of that waiver going to be?

It is a very, very tricky thing to do, and you have to be very careful in how you prepare your witnesses.

Moderator: The Supreme Court in Actavis says, "Our Federal patent laws do not give the patent holder the right to pay its competitors not to compete." And Actavis also said that "You don’t necessarily need to relitigate the patent merits in use cases." What does that mean? Are the patent merits still at issue, and how are they relevant? And aside from the patent merits, what are the procompetitive justifications for these agreements?

Baldridge: The question you asked actually goes right into the heart of this privilege issue, because it generally—or often—involves in-house counsel assessing the patent merits and inquiry by the lawyers as to whether that assessment of the strength of that patent had some bearing on the decision to settle. From the generic standpoint, and stated very quickly, we took the position that the strength of the patents at issue had absolutely nothing to do with our decision to settle. The unique fact to this case that allowed us to do that, was what you have already heard, that my client was experiencing some regulatory concerns. The judge had already instructed the jury we could not enter the market. So there were all kinds of reasons why a reasonable businessperson, wholly divorced from any legal analysis, could make a reasonable and justified decision to settle. That was the generic perspective in this trial.

[Page 130]

Schmidtlein: On the brand side, again, this goes back to several of the critical elements that the plaintiffs needed to prove in the case, and the jury found against them on causation. In a private plaintiff damage case, to say that the patent merits don’t matter makes no sense, notwithstanding whatever Justice Breyer says in Actavis. And this is why: You have to show that absent the settlement agreement, there would have been earlier generic entry. How are you going to prove that? You have to show that you would have either won the patent case and gotten to market before the license date. Well, that obviously implicates the patent holders. You have to show that somehow you would have launched at risk after the thirty-month stay expired, and, subsequently, you would have won the patent case. This is because a launch at risk that is later deemed unlawful, you can’t get damages for that unlawful entry.

Finally, this goes to Steve’s slide, you have to somehow show, absent the settlement agreement, you would have agreed to a different settlement agreement. And that different settlement agreement would have had the brand giving you earlier entry that would have sacrificed a great deal of brand profits. Again, you cannot delve into answering any of those questions while ignoring the merits of the patent case. That was our position.

Moderator: And now let’s hear the plaintiff’s perspective?

K. Johnson: We started out this case expecting we would spend time showing that the patents were weak. Our first witness we called to the stand, which was more for scheduling, more than any other reason, was a former FDA commissioner who explained that the FDA review of Nexium showed that it was not superior to Prilosec, which had direct bearing on the patents that were the subject of the settlement agreement. Testimony was then elicited from AstraZeneca and Ranbaxy witnesses that said the settlement merits played no role in our decision to settle, no role, zero role.

The testimony was that not one of the documents on the privilege log reflected any sort of internal assessment of what the patents actually looked like, the odds of prevailing at trial either from Ranbaxy or AstraZeneca. So faced with that testimony, frankly, it is a head-scratcher, right?

What do you do in a situation where you want to show that the patents are weak in order to show that generic entry by somebody else was possible, but you have actual testimony from the general counsel saying we never once thought about it in the context of actually negotiating the settlement?

Plaintiffs took the position that because the testimony was so emphatic, right, that only shows how the payment infected the settlement process from the very beginning, because from the start you had this no-AG promise embedded in the deal and no one ever talked about the patent merits. So, of course, there was no evidence you could show the jury of what a AstraZeneca and Ranbaxy proposed settlement without a payment would look like. There was no evidence showing what those parties thought the earlier date, without a payment, would be. Because from the very beginning of the negotiation, no one ever thought about the patent merits. It was all about the payoff.

[Page 131]

But, as we will get into, the relevant question isn’t what AstraZeneca and Ranbaxy actually talked about, it’s what reasonable pharmaceutical companies in AstraZeneca and Ranbaxy’s respective positions would have agreed to given competitive market conditions, i.e. in the absence of a payment.

Moderator: As we indicated earlier, the jury found that the agreements were unreasonably anticompetitive, but found no harm. We talked a lot about the causation element. In wrapping up, we would like each of the parties to take a minute or two to discuss the causation element.

Baldridge: You have heard it earlier from me, we were focusing on causation in our case. One thing that I thought was critical from a trial standpoint is the plaintiffs did create their but-for world, and they put an expert on the stand. That was unusual, let’s just say. That in and of itself isn’t that unusual, but at the same time, as Kristen did mention, they had the head of the FDA on the stand. And the head of the FDA on the stand was never asked the question, "Could there have been an earlier approval by the FDA, could there have been an earlier entry date?" Instead, the plaintiffs went with this other expert. From my standpoint, from the causation standpoint, that said it all. You had the head of the FDA and didn’t get the answer, but you asked this expert over here, who had significant problems in the cross-examination. From the but-for standpoint, no one could get on with the FDA and why that approval wasn’t honed in more directly with someone qualified to answer that question.

Schmidtlein: Just one little tweak on that defense. The jury didn’t even reach that question of the sort of "no FDA approval" defense. The jury found for the defendants before they even got to that series of questions. So this was always going to be a major problem. One last point is these cases really do sort of cry out for sort of special verdict forms. I have tried cases where I think antitrust cases oftentimes are good for those, and this was, I think, useful.

Moderator: We’d like to hear the plaintiffs’ perspective on causation.

Shadowen: I am going to keep it very general because this is one of the thrusts of the ongoing appeal. Let me talk about these sets of cases generally, rather than this case in particular. As John mentioned, plaintiffs have the burden of saying what would have happened in the but-for world. In the but-for world, you have three avenues to earlier generic entry.

One, you prove the generic would have won the underlying patent litigation. Two, you prove that the generic manufacturer would have waited out the thirty-month stay and launched at risk. And then there’s going to be a hell of a legal issue one day whether, if you go that path, you have to prove that the generic would have ultimately won the underlying patent litigation. Because, as John asks, is there antitrust injury if consumers were deprived of an interim set of sales that turned out to be infringing sales? That’s going to be an interesting legal issue someday.

Third avenue is to say that, but for the payment, the manufacturers would have agreed to an earlier entry date. And it is on that one, I think that the plaintiffs in the future are going to focus very, very heavily on saying it’s not a subjective test—would these manufacturers have agreed to an earlier entry date—but rather, would reasonable manufacturers in that position have agreed to an earlier entry date? Otherwise it is just too easy for John to put his witness on the stand and say, "Oh, no, absolutely not. I made that payment out of the goodness of my heart. Absent that payment, I still would have insisted on exactly the same entry date." So we are going to be better off in the future, rather than cross-examining heavily, which we’ll do, but rather than relying solely on cross-examination of the subjective views and intentions of the defendants’ executives, to have economists with very solid studies come in and say, "Reasonable manufacturers in this position would have found it in their mutual economic interests to agree on a payment-free earlier entry date."

[Page 132]

K. Johnson: If you think about it in a hypothetical context where a jury finds that there is a "large and unjustified payment" and the jury finds that the anticompetitive consequences outweigh the procompetitive benefits—take that as a starting point. The law then requires that a jury decides what would have happened in the absence of that payment. It has to be done, right. I am not making it up. It is not a fantasy world; it has to be done. You can’t say, "It is too hard." You can’t get in your Tardis time machine and go see what some other universe looks like. But what you can do is look at the economics, stupid. You look at what would have actually happened with competitive consequences. And that is what Steve is saying. I think you’ll see in future trials, you’ll see a lot more economic testimony about what logically would have flown from those competitive circumstances.

Schmidtlein: With that, I say unleash the Daubert hounds.

Moderator: All the economic experts should perk up with that comment. We have only a minute or two; would any of our panel members want to give a Tweet-length tip from the lessons you learned from this trial?

Baldridge: I’ll say the same one I say every time: I am not an antitrust lawyer, although I have tried a bunch of antitrust trials. We all have a tendency to look down on juries, that’s a huge mistake. Juries usually get it right. And talking to them like they are something of low ilk or can’t understand these issues is a huge mistake. If you don’t believe that, don’t try cases, sit back and write white papers and send them to the FDA.

K. Johnson: I have one serious and one funny. Serious: if this trial taught me anything, is that you have to adapt at a moment’s notice, everything changes so quickly that you have to turn on a penny. Funny: don’t wear slingbacks when examining witnesses, because it is very embarrassing later when someone says, "Oh, I remember you. You are the one with the loud shoes."

Schmidtlein: I will agree. You have to expect the unexpected. The judges are doing and will continue to do their very best to try to navigate through all of these very difficult issues. You need to be flexible. The last thing I will say that was sort of taught to me years ago is try to convince, put your trial strategy together to play to things that juries believe. Trial lawyers by definition have enormous egos, and sometimes we think we can convince anybody of anything. And one of the things I try not to forget is that is completely nonsense. People who have a firm understanding or a belief system in certain things, you are not likely going to be able to change their views. You are just not that good, and their understanding of the truth is that firmly held. But what you can do is to try to focus on things and frame issues and put your case on so that it plays to things that people already naturally understand and believe.

[Page 133]

Shadowen: I will reiterate what Doug said. This was a very attentive jury. We have complaints, obviously, that the trial judge improperly prevented us from putting compelling facts in front of them and gave them confusing and erroneous instructions, but we will see on round two what happens.

[Page 134]

——–

Notes:

1. Cheryl Lee Johnson is in the Antitrust Section of the California Attorney General’s Office, the Editor-in Chief of California Antitrust & Unfair Competition Law, and a former Chair of the California State Antitrust & Unfair Competition Section. Any views represented here are the author’s own, and in no way represent the views of the Antitrust Section or the California Attorney General’s Office.

2. The following two subsections are drawn, in part, from the author’s earlier article regarding pay-for-delay. See Cheryl Lee Johnson, Cipro’s $400 Million Pay for Delay: How California Law and Courts Can Make a Difference in Reverse Payment Challenges, 67 Rutgers U.L. Rev. 721 (2015).

3. FTC, Pay-for-Delay: How Drug Companies Pay-Offs Cost Consumers Billions 8 (2010) [hereinafter FTC, Pay-for-Delay] (noting that in a mature generic market, generic prices are on the average 85% lower than the pre-entry branded drug price); Alison Masson & Robert L. Steiner, FTC, Generic Substitution and Prescription Drug Prices: Economic Effects of State Drug Product Selection Laws 1(1985).

4. For a detailed discussion of the regulatory framework in which reverse payment agreements are concluded, see F.T.C. v. Actavis, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2223, 2228 (2013); In re K-Dur Antitrust Litig., 686 F.3d 197, 203-04 (3d Cir. 2012); C. Scott Hemphill, An Aggregate Approach to Antitrust: Using New Data and Rulemaking to Preserve Drug Competition, 109 Colum. L. Rev. 629, 635 (2009).

5. In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 42 F. Supp. 3d 231, 240 (D. Mass. 2014).

6. Cf. FTC, Pay-for-Delay, supra note 3, at 1 ("The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) investigations and enforcement actions against pay-for-delay agreements deterred their use from April 1999 through 2004. . . . Since 2005, however, a few appellate courts have misapplied the antitrust law to uphold these agreements. Following those court decisions, patent settlements that combine restrictions on generic entry with compensation from the brand to the generic have reemerged." (footnotes omitted)).

7. See Actavis, 133 S. Ct. at 2234-35, 2237 (suggesting parties can settle without payments that suggest monopoly sharing); In re K-Dur, 686 F.3d at 216, 218; Hemphill, supra note 4, at 635.

8. 466 F.3d 187 (2d Cir. 2005).

9. Valley Drug Co. v. Geneva Pharms., Inc., 344 F.3d 1294, 1308-09 (11th Cir. 2003); Schering-Plough Corp. v. F.T.C., 402 F.3d 1056, 1068 (11th Cir. 2005); In re Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride Antitrust Litig., 363 F. Supp. 2d 514 (E.D.N.Y. 2005); Tamoxifen, 466 F.3d at 208-09.

10. This misnomer was particularly inapt given that this is the term the United States Supreme Court has used to define the intersection between antitrust and patent law in assessing such issues as whether patent licensing agreements were unduly restrictive, and is a standard that involves an actual inquiry into the scope of the patent. See, e.g., Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395 U.S. 100, 136 (1969).

11. Press Release, FTC, FTC Study: In FY 2012, Branded Drug Firms Significantly Increased the Use of Potential Pay-for-Delay Settlements to Keep Generic Competitions off the Market (Jan. 17, 2013), available at http://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2013/01/ftc-study-fy-2012-branded-drug-firms-significantly-increased. In a 2014 report, the Bureau of Competition found that of the twenty-nine actual or potential pay-for-delay agreements entered into in 2013, which covered more than twenty-one drugs with combined annual sales in the United States of $4.3 billion, fourteen had compensation in the form of cash purporting to reimburse the generic’s fees; four included promises not to launch an authorized generic; ten restricted generic entry with declining royalty rates and other possible forms of compensation not readily discernible; and that most of the agreements included side business deals between the branded company and the generic manufacturer. Bureau of Competition, Agreements Filed with the Federal Trade Commission Under the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003: Overview of Agreements Filed in FY 2013: A Report by the Bureau of Competition 1-2 (2014) [hereinafter Agreements Filed in FY 2013]. In its most recent 2016 report, another twenty-one reverse payment agreements were inked post Actavis, shielding $6.2 billion in annual drug sales from competition in addition to several other agreements that the FTC could not parse. Bureau of Competition, Agreements Filed with the Federal Trade Commission Under the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003: Overview of Agreements Filed in FY 2014: A Report by the Bureau of Competition 1 (2016).

12. Use of the term "payments" here is not limited to cash payments, but rather denotes any form of consideration or value given in exchange for an agreement to delay competition. Most recent agreements eschew straight cash payments and instead include promises not to launch an authorized generic or other non-cash forms. See Agreements Filed in FY 2013, supra note 11, at 1-2; Michael A. Carrier, Payment After Actavis, 100 Iowa L. Rev. 7, 42 (2014). While there has been considerable litigation concerning the application of Actavis to non-cash settlement agreements, the two Federal Circuit cases addressing the issue, In re Loestrin 24 Fe Antitrust Litig., 2016 WL 698077 (1st Cir. Feb. 22, 2016) and King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. v. SmithKline Beecham Corp., 791 F.3d 388, 403 (3d Cir. 2015), followed some eight district court decisions in rejecting such a limitation as contrary to the spirit and letter of the Actavis decision. Loestrin, 2016 WL 698077, at *10.

13. See F.T.C. v. Actavis, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2223, 2235 (2013).

14. See, e.g., Ark. Carpenters Health & Welfare Fund v. Bayer AG, 604 F.3d 98, 109-10 (2d Cir. 2010); In re K-Dur Antitrust Litig., 686 F. 3d 197, 213 (3d Cir. 2012).

15. 686 F. 3d at 197.

16. See In re Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride Antitrust Litig., 544 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2008); F.T.C. v. Watson Pharms., Inc., 677 F.3d 1298 (11th Cir. 2012).

17. The United States Supreme Court earlier denied certiorari in the following cases: La. Wholesale Drug Co., Inc. v. Bayer AG, 562 U.S. 1280 (2011); Ark. Carpenters Health & Welfare Fund v. Bayer AG, 557 U.S. 920 (2009); Joblove v. Barr Labs, Inc., 551 U.S. 1144 (2007); F.T.C. v. Schering-Plough Corp., 548 U.S. 919 (2006); Valley Drug Co. v. Geneva Pharms., Inc., 543 U.S. 939 (2004); and Andrx Pharms., Inc. v. Kroger Co., 543 U.S. 939 (2004).

18. F.T.C. v. Watson Pharms., Inc., 133 S. Ct. 787 (2012). Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc. became Actavis, Inc. See Actavis, 133 S. Ct. at 2229.

19. K-Dur, 686 F.3d at 216-17.

20. Id. at 215-16, 218.

21. Actavis, 133 S. Ct. at 2234-35 (noting that payments by patentee in return for staying out of the market simply keeps prices at patentee-set monopoly levels while dividing those monopoly returns with its rivals all at the expense of the consumer); id. at 2237 (noting that large unjustified payments can bring the risk of significant anticompetitive effects).

22. Id. at 2232-33.

23. Id. at 2231 (reasoning that it would be "incongruous to determine antitrust legality by measuring the settlement’s anticompetitive effects solely against patent law"); id. at 2230 (finding that even if the agreements’ anticompetitive effects are within the scope of the exclusionary potential of the patent, they are not immunized from antitrust attack); id. at 2234 ("[P]ayment in effect amounts to a purchase by the patentee of the exclusive right to sell its product . . . .").

24. Id. at 2233 (dismissing the dissent because it identifies no patent statute that grants a patentee the right to pay its competitors, whether expressly or by fair implication, and noting that such a right would be irreconcilable with the patent policy of eliminating unwarranted patent grants); id. at 2232 (emphasizing that patent related settlement agreements can violate the antitrust laws though the patents were valid because the Sherman Act strictly limits concerted action by patent owners); id. at 2231 (noting that the Court must balance whether the patent statute specifically gives a right to restrain competition in the manner challenged against available lesser restraints and the prohibitions against monopolies).

25. Id. at 2237.

26. Id. at 2234.

27. Id. at 2231, 2234.

28. Id. at 2237.

29. Id. at 2231.

30. Id. at 2238.

31. See, for example, the Fall 2013 issue of Antitrust Magazine, which is dedicated to this commentary and contains some nine articles on the topic. See also Carrier, supra note 12, at 10 (citing numerous articles on the topic); Allison A. Schmitt, Competition Ahead? The Legal Landscape for Reverse Payment Agreements After Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis Inc., 29 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 493 (2014); Seth Silber, Jonathan Lutinski & Ryan Maddock, "Good Luck" Post-Actavis: Current State of Play on "Pay-for-Delay" Settlements, Competition Pol’y Int’l Antitrust Chron. (Nov. 2014). Some of those same issues were parsed out by the California Supreme Court, which addressed the standard of review and burden of proof in challenges to reverse payment agreements under California state antitrust law in In re Cipro Cases I & II, 61 Cal. 4th 116 (2015).

32. See, e.g., Brief of F.T.C. as Amicus Curiae in Support of No Party, In re Wellbutrin XL Antitrust Litig., No. 15-3559 (3rd Cir. Mar. 11, 2016) (arguing that Actavis applies to any reverse payments even if the underlying patent litigation continues, that proof of actual delayed entry is not required, and that defendants must prove any pro-competitive benefits); Silber, supra note 31 (citing numerous cases on the topic).

33. In re Nexium Antitrust Litig., 777 F.3d 9, 12 (1st Cir. 2015).

34. Pub. L. No. 98-417, 98 Stat. 1585 (codified at 21 U.S.C. § 355 (1984)).

35. HR Rep. No. 98-857, pt 2, at 4 (1984); see also In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 968 F. Supp. 2d 367, 378 (D. Mass. 2013).

36. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, an applicant may certify (1) that the associated branded drug is not patented, (2) that the patent for the branded drug is expired, (3) that the generic will not be marketed until the patent covering the branded drug has expired, or (4) that the applicant believes the patent covering the branded drug is either not valid or not infringed. See 21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(2)(A).

37. In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litigation, 42 F. Supp. 3d 231, 247, 249 (D. Mass. 2014).

38. Id. at 247.

39. Id.

40. Id. at 249, 256.

41. Id. at 247.

42. In re Nexium Antitrust Litig., 777 F.3d 9, 13 (1st Cir. 2015).

43. Id. at 14.

44. Id. at 13-14.

45. Id. at 14; see also In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 309 F.R.D. 107, 114-24 (D. Mass. 2015).

46. Nexium, 42 F. Supp. 3d at 243-44 (D. Mass. 2014).

47. Nexium, 309 F.R.D. at 117-18.

48. The protracted pretrial history of the case is set out in the court’s lengthy decision denying a motion for a new trial, see id. at 114-18, as well as the plaintiffs opening brief on appeal, see Consolidated Brief of Direct Purchaser and End-Payor Class Plaintiffs-Appellants at 51-54, In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., No. 15-2005 (1st Cir. Feb. 5, 2016).

49. Consolidated Brief of Direct Purchaser and End-Payor Class Plaintiffs-Appellants, supra note 48, at 57 (internal quotation marks omitted) (footnote omitted).

50. Nexium, 309 F.R.D. at 119-20.

51. Id. at 120 (the defendants "howled" but the court denied the motions for mistrial).

52. Id.

53. Id. at 124-25.

54. Id. at 125.

55. Id.

56. Id. at 110.

57. In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., No 15-2006 (3d Cir. Sept. 11, 2015).