Litigation

Interview With United States Senior District Judge Jeffrey T. Miller

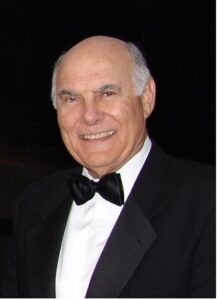

Jeffrey T. Miller has served as a United States District Judge for the Southern District of California since he was appointed in 1997. At his confirmation hearing, Senator Dianne Feinstein said, “Simply put, Judge Miller is one of the most respected and trusted judicial figures in the San Diego area. He is both fair minded and thoughtful, yet remains tough and decisive.” Judge Miller assumed senior status in 2010, and has continued to preside over a wide variety of civil and criminal cases. Prior to joining the federal bench, he was a San Diego Superior Court Judge between 1987 and 1997, after having served as a Deputy Attorney General for the California Attorney General’s Office for 18 years as a trial and appellate litigator, primarily in the area of government tort liability. Judge Miller earned his law degree and his undergraduate degree from UCLA.

In this interview, Judge Miller shares what it was like to argue before the United States Supreme Court, what led him to consider becoming a judge, the difference between serving as a judge in state and federal court, and his views on what makes a successful advocate. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Before joining the bench, you had a distinguished career in public service with the California Attorney General’s office. What made you decide to become a judge?

The prospect of becoming a judge never entered my mind, even after 18 years of practice in the public service arena, in both the trial and appellate courts. But one fine day, in 1986, as luck would have it, one of Governor Deukmejian’s judicial advisers, a San Diego Superior Court Judge before whom I had tried cases, encouraged me to consider submitting my name for Superior Court. I wrestled with the idea and tried to project myself into the judicial world. Ultimately, the decision to go for it was an easy one. I had done trial and appellate work, both civil and criminal at all levels, including the United States Supreme Court. I felt ready for a new challenge.

What was it like to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court?

Well, the thought of arguing before the United States Supreme Court was daunting in each of the two cases I had before the Supreme Court, and, in a word, a bit “terrifying” before the first in the lead-up to the argument. I happened to learn of the Court taking the case when a newspaper reporter called me for a comment. After the initial shock, both the briefing and oral argument preparation were extensive and compressed into an expedited schedule. Like everything in the law, preparation is vital, never more so than that required for an argument before the Supreme Court. After many hundreds of hours of preparation for a half hour of oral argument, I stood at the lectern in that majestic chamber. I was surprised at how close the attorney’s lectern is to the bench. There was a feeling of intimacy, as the ends of the bench are curved, or angled inward, the better for the justices to take in the argument and to see each other. I was struck by the courtesy and civility of the court. It was an atmosphere conducive to a high level of oral advocacy, a “conversation” if you will. Time flies by. The half hour seems like five minutes. And when the lectern warning light flashes, signaling that only a few minutes remain, it seems time has warped.

All in all, it was a joyful ordeal in retrospect, an opportunity to practice at the pinnacle of our calling.

What was the biggest difference between serving in Superior Court & Federal District Court?

Let me preface my response by saying judicial skills and temperament are easily transferrable from one bench to another. Case management and trial practice are more similar than not. As a matter of fact, in 1990, the San Diego Superior Court used the federal court’s “independent calendar” system – by which a civil case is assigned to one judge for all purposes – as a model for its conversion to the independent calendar system.

The biggest change I encountered was going from a large metropolitan Superior Court of over 100 judges (after the Municipal Court was consolidated into the existing superior court) to a Federal District Court with 13 district judges, comprised of small, tightly-knit “federal families” within the respective chambers. I had begun to experience that type of working culture on the Superior Court when, in 1990, I was one of eight judges to start the independent calendar system, with each judge modeling the federal system for chambers staffing.

In the Southern District of California, we have a very user-friendly federal bench, according to the local legal culture. For example, in both the federal and state courts, attorneys have prompt and direct access to chambers for the setting and briefing of motions. The fact that our bench has always been comprised of many Superior Court Judges may have something to do with the consistency.

What surprised you when you arrived in the federal system?

The biggest surprise was having lunch with Chief Judge Judy Keep just before I was sworn in. She advised me that my soon-to-be colleagues could hardly wait until I came on duty, and they had collectively hand-picked approximately 300 civil cases to be re-assigned to me. Indeed, there were smaller surprises within the larger surprise.

Please tell me about a time in your life when you could have taken two very different paths. What path did you take? How did you choose that path?

After clerking (“externing” in today’s parlance), with a small firm and its exceptional mentor, Gideon Kanner, who later became Professor Emeritus at Loyola Law School, private practice seemed to be my destiny after I was invited to join the firm. Then, a measure of good fortune intervened, resulting in a course correction. While in my last year of law school, and curious about the public sector, I interviewed with the California Attorney General’s office. Unexpectedly, a neighbor I casually knew from down the block conducted the interview. Little did I know that Dan Kaufmann, the interviewer, was not only an attorney, but the Assistant Attorney General In Charge of the Los Angeles office. The interview went well, and I was invited to meet some of the senior attorneys in the office, many of whom were leaders in their areas of practice. Some would later become judges, including California Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald George and California Supreme Court Associate Justice Wiley Manuel. A position was offered, and a career of public service was off and running. Public service, indeed, was the right path right out of the starting blocks.

What is your advice to lawyers (new or experienced) about how to be successful advocates?

I start with the writer, David Foster Wallace, who famously told the story of two young fish swimming along when they encounter an older fish, who nods and asks, “Morning boys. How’s the water?” The two youngsters swim a bit farther, when one looks to the other and says, “What the hell is water?”

And, then, there was my UCLA law school torts professor, William Cohen, who, upon sensing his students needed a dose of humility at the end of the course, likened lawyers to plumbers, exclaiming, “We are all plumbers in life. We just work on different sets of pipes.”

I think the musings of Wallace and Cohen are linked in a way that might be helpful to a new lawyer. We all must recognize the importance of self-awareness and humility as we go forward in law and life. That judicial giant, Learned Hand, in 1944, tried to define liberty as he addressed new citizens at a naturalization ceremony in New York City: “What then, is the spirit of liberty? I cannot define it; I can only tell you my own faith. The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is that spirit which seeks to understand the minds of other men [and women].” The new lawyer is about to enter upon what can be the most adversarial, challenging, and humbling profession of all. We are all taught to practice civility, integrity, and professionalism. And we should. But beyond that, I would especially tell the new lawyer to be kind, fair, humble, and, as Judge Hand counseled, not too sure that you are right. Be reasonable, but, as important, see the reason behind the other’s position. Ultimately, know who you are, be conscious about the formation and pursuit of goals, ever aware while navigating the currents of our profession, “this is water.”

A significant part of being a good lawyer is preparation; that is the great equalizer in the profession. Success depends upon hard work and preparation and commitment. Famed UCLA former men’s basketball Coach John Wooden said: “failing to prepare is preparing to fail.” Truer words were never spoken. Similarly, successful attorneys have mastered the facts of their case and the law through hard work, and they have the foresight to prepare for situations that might arise, such as missing or surprise witnesses, or technological failures in the courtroom.

Interviewer Information: Judge Miller was interviewed by Christina McCall in December of 2022. Ms. McCall is a federal prosecutor in Sacramento, California, who had the privilege of serving as a law clerk for Judge Miller in the 2004-2005 term. Any views expressed herein do not reflect the position of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, or the U.S. Department of Justice.