Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Winter 2017-18, Vol. 27, No. 1

Content

- Antitrust's Hidden Hook In Drug Price Increases

- Causation Principles In Pharmaceutical Antitrust Litigation

- Certificates of Public Advantage: Bypassing the Ftc In Healthcare Mergers?

- Chair's Column

- Digital Health Privacy: Old Laws Meet New Technologies

- Editor's Note

- Masthead

- Rethinking Healthcare Data Breach Litigation

- The Efficiencies Defenestration: Are Regulators Throwing Valid Healthcare Efficiencies Out the Window?

- The Proximate Cause Requirement In Private Reverse Payment Antitrust Litigation

- Uncertainty and Scientific Complexity: An Introduction To Economic Forces That Drive Current Debates In Healthcare Antitrust

- What Past Agency Actions Say About Complexity In Merger Remedies, With An Application To Generic Drug Divestitures

- Where Art Thou, Efficiencies? the Uncertain Role of Efficiencies In Merger Review

- Empirical Evidence of Drug Companies Using Citizen Petitions To Hold Off Competition

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE OF DRUG COMPANIES USING CITIZEN PETITIONS TO HOLD OFF COMPETITION

By Robin Feldman,1 John Gray,2 & Giora Ashkenazi3

I. INTRODUCTION

The United States patent system is designed to reward innovation and spur new technological growth. While this is incredibly effective in most fields, it can be especially problematic in the pharmaceutical industry where the inelasticity of demand for products has allowed for exorbitant drug prices. This is most clearly seen in the effect that the entry of generic drugs has on the market. Since 1984, more than 10,000 generics have entered the market,4 and the percentage of prescriptions filled with generics rose from just 13 percent in 19805 to around 86 percent by 2013.6 Notably, the dramatic rise of generics has saved the public inordinate amounts of money. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that consumers saved more than $217 billion through the use of generics in 2012 alone, with total savings of $1.68 trillion from 2005 to 2014.7 It is, therefore, of the utmost importance to ensure that generic drugs enter the market properly as patents expire. Brand-name pharmaceutical companies have long been known to play a myriad of games to delay generic entry for as long as possible.

In a recently published book and article,8 co-authored by team members at the UC Hastings Institute for Innovation Law, we expose troubling behavior in which pharmaceutical companies use the FDA’s citizen petition process to delay entry of generic competitors. Examining more than a decade of FDA data related to citizen petitions, along with data related to generic drug approvals, the study provides broad empirical evidence that citizen petitions at the FDA have become an important pathway for strategic behavior by pharmaceutical companies.

[Page 62]

Improper citizen petition behavior arises against the backdrop of soaring drug prices in the United States, a problem exacerbated by the lack of effective competition in pharmaceutical markets.9 Although citizen petitions provide only one pathway for delaying competition, the study examines this essential piece of the puzzle. Key results from the study include the following:

- The FDA’s citizen petition process is one of the critical pathways involved in the modern generation of generic drug delay, playing a role in various game-playing strategies.

- Citizen petitions from brand name and generic companies seeking to delay competitors have effectively doubled since 2003.

- Of all citizen petitions at the FDA (including those concerning tobacco, food, dietary supplements, medical devices, etc.), nearly 15 percent have the potential to delay generics, climbing to 20 percent in some years.

- Many citizen petitions from competitor companies appear to be an eleventh-hour effort to hold off generic competition. In fact, the most common category of delay-related petitions was that of petitions filed within six months of generic approval. This is particularly noteworthy given that the overwhelming majority of citizen petitions are denied.10

- In short, the results suggest that many competitor petitions are filed late in the game, as a last-ditch attempt to delay competition just a little longer, even though the petitions are unlikely to be successful.

- Congressional reforms enacted in 2007 have not stemmed the tide.

II. BACKGROUND

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 revolutionized the pharmaceutical industry, creating a streamlined pathway for approval of generic drugs. The goal was to frontload the approval process of generics during the patent term to allow them to enter the market as soon as the patent on the original drug expired, thereby increasing competition and driving down prices for patients and the healthcare system as a whole. The Act introduced the concept of an Abbreviated New Drug Application ("ANDA"), allowing prospective generics to use clinical data from approval of the original, brand-name drug to demonstrate safety and efficacy. Rather than repeating the lengthy and costly clinical trials, a generic hopeful need only demonstrate that its own product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. Hatch-Waxman also provides a complex process for generic applicants to initiate and resolve patent issues prior to bringing the drug to market. Complexity breeds opportunity,11 however, and Hatch-Waxman’s complicated language opened the door to strategic behaviors that drug companies have deployed to maintain competition-free zones for as long as possible. The tactics have evolved over time, and the modern generation of strategic behaviors frequently involves obstruction tactics to prevent or delay approval of generic competitors. One such method involves filing citizen petitions with the FDA.

[Page 63]

Citizen petitions were designed as a mechanism for independent scientists and citizens to raise concerns about a food product or a drug. The process, however, has been hijacked by pharmaceutical companies to challenge and delay drug applications from potential competitors. Drug companies use a variety of approaches in their citizen petitions, including asking the FDA to require of the generic what it already requires for any generic application, raising safety concerns, and asking the FDA to preserve or add new exclusivities for the brand-name drug. Although the FDA eventually rejects the vast majority of these demands, it spends time and resources to review them; time and resources that are diverted from considering the generic competitor’s application. In addition, although the FDA must respond to a citizen petition within five months, a delay of such time period can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for a blockbuster drug. Significantly, those five months can be added onto other delay tactics, which the branded company strings out, one after the other. While competitors languish on the sidelines, the brand-name company remains free to charge sky-high prices.

Anecdotal evidence has suggested that drug companies abuse the citizen petition process, but little empirical evidence had existed. This leaves the pharmaceutical industry free to suggest that the behavior is limited to a few bad apples. For example, in testifying before a U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee this summer, one witness sympathetic to the pharmaceutical industry argued emphatically that suggestions of improper citizen petition behavior were no more than "anecdote and rhetoric."12

III. Method

To examine whether widespread abuse of the citizen petition process exists, we set out to assemble a database of all citizen petitions filed with the FDA between the years 2000 and 2012, which could potentially delay generic entry. This task was tremendously difficult, to say the least. Some of the most important information about citizen petitions must be pieced together or estimated; at other times, it simply does not exist. For example, the FDA does not expressly reveal the date on which the generic application for a drug was filed, making it difficult to determine the timing relationship between a generic application’s filing date and the date upon which a potentially delaying citizen petition was filed. Selected details of the methodology include the following:

[Page 64]

- We compiled all FDA citizen petitions and related documents filed between 2000 and 2012.

- We identified citizen petitions related to pharmaceuticals, with a particular focus on generic drugs.

- We read each remaining citizen petition and determined which of these petitions were related to generic drugs or had the power to delay generic approval, regardless of the merits or circumstances of the petition.

- We constructed a data set of all generic applications approved between 2006 and 2015, recording the approval date for each application.

- We compiled filing dates for the generic applications, pulling them when available from PDFs of letters within the FDA’s databases. When filing information was not publicly available, we were able to estimate a filing date down to the quarter-year for most drugs.

- We matched each citizen petition with the generic application most relevant to the requests made in the petition.

- Using these citizen petition-generic application pairs, we constructed metrics with the goal of isolating the timing of petitions during the generic drug approval process.

The final pool of citizen petitions with the potential to delay the introduction of generic drugs consisted of 249 citizen petitions filed between 2000 and 2012. We then matched these petitions with the generic application that would be most directly affected. At the end of this process, 164 citizen petitions of the original 249 originally identified were linked to generic applications that had data available: either a filing date, an approval date, or both.13 Out of those 164 petitions, 152 (or 61 percent of the total 249 petitions) were linked to generic applications with both the filing date and approval date.14

IV. RESULTS

The results of the study provide empirical evidence that the citizen petition process at the FDA has become a key avenue for strategic behavior by pharmaceutical companies to delay entry of generic competition.

[Page 65]

A. Rise in Citizen Petitions with the Potential to Delay

As seen in Table I below, a notable percent of citizen petitions seems to have the potential to delay generic entry. Looking at the overall number of citizen petitions filed at the FDA on any topic, fourteen percent have the potential to delay a generic drug application, climbing to roughly twenty percent in some years. That means one in five of all citizen petitions to the FDA—not just those concerning pharmaceuticals—have the potential to delay generic competition in some years. This table also shows that starting around 2003 and 2004, petitions rose in popularity as a way to delay generics or raise issues about generics. Not only did the number of citizen petitions rise noticeably after 2002, but the number of delay-related petitions also sharply increased as a proportion of all petitions.

TABLE I—ALL DELAY-RELATED PETITIONS, BY YEAR

| YEAR | NUMBER OF DELAY-RELATED PETITIONS |

PERCENTAGE OF YEARLY TOTAL PETITIONS |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2 | 2/47 = 4.3% |

| 2001 | 4 | 4/63 = 6.3% |

| 2002 | 5 | 5/106 = 4.7% |

| 2003 | 12 | 12/120 = 10.0% |

| 2004 | 26 | 26/178 = 14.6% |

| 2005 | 15 | 15/148 = 10.1% |

| 2006 | 24 | 24/184 = 13.0% |

| 2007 | 25 | 25/160 = 15.6% |

| 2003 | 23 | 23/166 = 13.9% |

| 2009 | 32 | 32/171 = 18.7% |

| 2010 | 31 | 31/149 = 20.8% |

| 2011 | 22 | 22/157 = 14.0% |

| 2012 | 28 | 28/141 = 19.9% |

| TOTAL | 249 | 249/1,790= 13.9% |

B. When Are Citizen Petitions Filed in Relation to Final Approval?

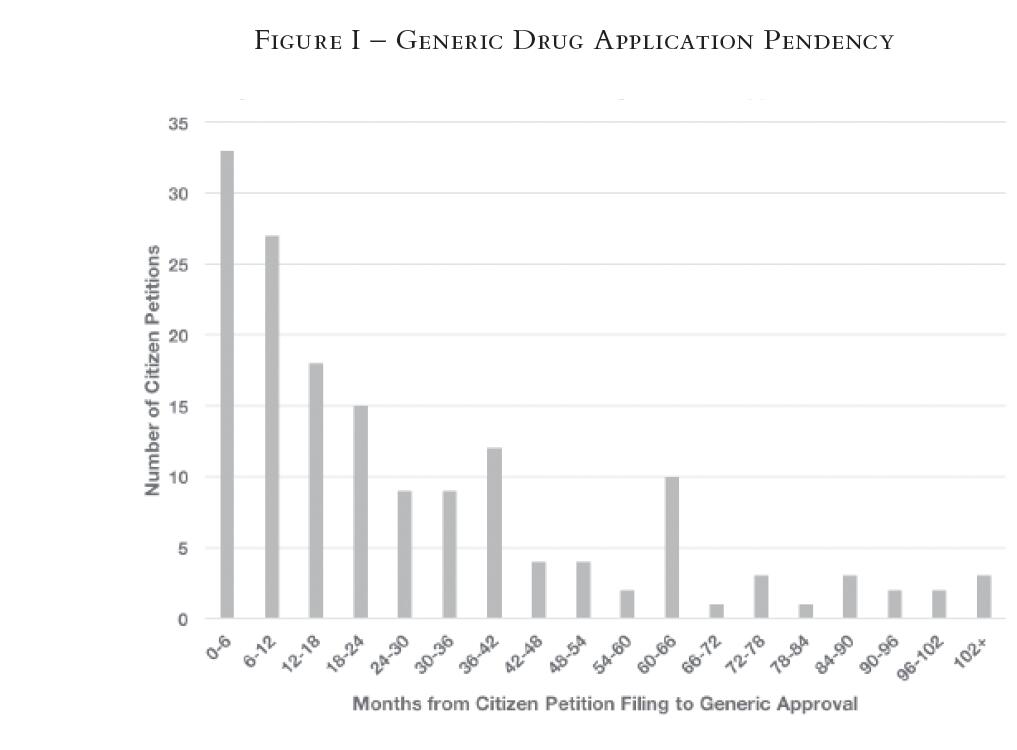

The results also demonstrate that many drug companies are filing citizen petitions as a last-ditch effort in the period immediately before generic approval. Moreover, the timing suggests that many of these citizen petitions appear to be the very last barriers standing in the way of final generic approval. These implications emerged when we graphed the amount of time between when a citizen petition was filed and when the generic application was approved.

In particular, our original hypothesis was that if citizen petitions are being used systematically to delay the approval of generics, petitions might be deployed most effectively for that purpose near the end of a generic approval cycle. If filed earlier, the petition could merely introduce a review process running parallel to the rest of the generic approval process.

The data confirm this hypothesis. As seen in Figure I below, there is a clear trend in favor of citizen petitions filed shortly before the FDA approves a generic. In fact, the most common category was "0—6 months," with 33 petitions, or 21 percent of the total,15 filed with up to six months or less remaining before the FDA approved the generic. Considering that the average length of time from generic filing to approval is roughly four years, this category occurs most often during the last leg of the approval process.

[Page 66]

In other words, the trend is toward an increasing number of petitions as one moves closer to the final approval date. Thus, this histogram suggests that delay-related citizen petitions are often filed in the final stages of generic approval to raise concerns at the last minute, rather than early or midway through the process. This pattern potentially extends the length of the generic application approval process, thus delaying the market entry of generic competition.

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 67]

C. How Did the 2007 Amendments Affect Citizen Petition Timing?

After years of hearings and debate on numerous FDA issues, Congress passed a large package of amendments in 2007, which included the largest reform of the citizen petition process in the petition program’s thirty-year history.16 These changes attempted to address concerns with citizen petitioning at the FDA, ranging from growing petition backlogs to signs that the process was being used inappropriately.17

Specifically, the 2007 Amendments added a subsection, 505(q), applying a new set of regulations to all citizen petitions that ask the FDA to take action related to a pending generic application. The section requires that the FDA respond to such petitions within 180 days, a period that was shortened to 150 days in 2012.18 If a petition falls under section 505(q), the person filing the petition must certify that 1) the petition is not frivolous, 2) all information favorable and unfavorable has been provided, and 3) the petitioner did not intentionally delay filing the petition. The petition must also provide the date when the filer first became aware of the concerns and the names of those who are funding the petition.19 Finally, section 505(q) grants the FDA the power to summarily deny any petition that the Agency believes was filed with the "primary purpose" of delaying generic approval, if the petition also does not "on its face raise valid scientific or regulatory issues."20 Together, the provisions of section 505(q) were meant to speed the process and end any abuse of citizen petitions by pharmaceutical companies.

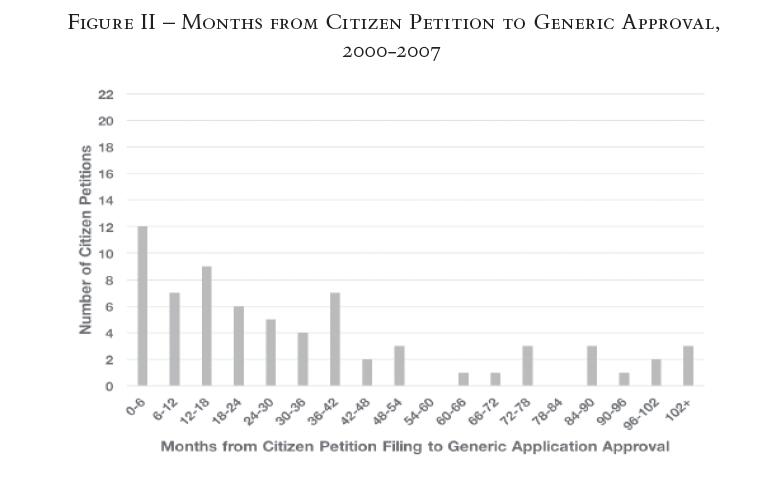

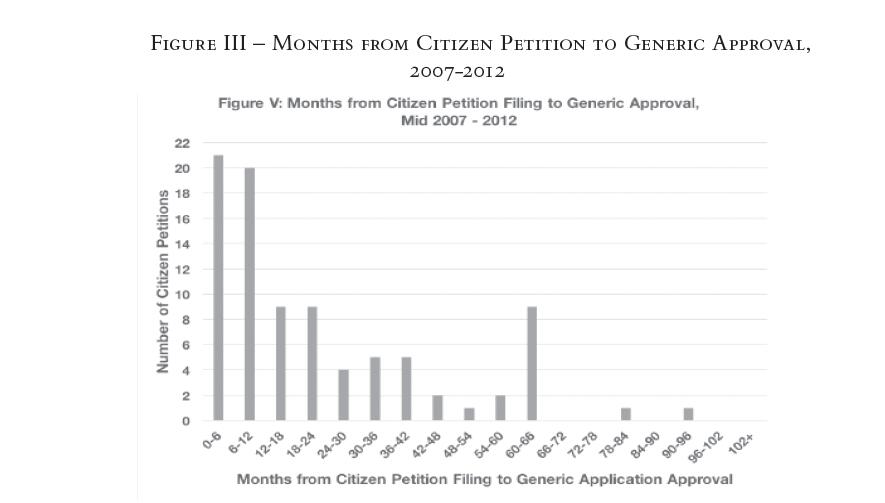

To test the impact of the 2007 Amendments, we compared the periods before and after 2007. Figure II below, which looks specifically at the period before the 2007 Amendments, shows that 41 percent of petitions were filed within a year and a half of approval.21 In the period after the 2007 Amendments, the existence of last-minute petitions with the potential to delay has not abated. In fact, the trend is even more dramatic (see Figure III). Fifty-six percent of the petitions were filed within a year and a half of generic approval.22

Moreover, in the post-2007 period, a remarkable 46 percent of petitions were filed within a year of generic approval. The "0—6 months" and "6—12 months" categories were by far the most popular, garnering 24 percent and 22 percent of the total, respectively.23 The biggest exogenous shift between the 2000 to mid-2007 histogram (Figure II) and the mid-2007 to 2012 histogram (Figure III) is, of course, the enactment of the 2007 Amendments. Its most notable change—requiring that the FDA respond to citizen petitions within 180 days—may explain why the post-2007 graph (Figure III) paints such a dramatic picture of citizen petition timing.

[Page 68]

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 69]

Image description added by Fastcase.

The FDA’s 180-day time limit for responding to citizen petitions equates to six months, which aligns with our smallest category of 0—6 months. This has two implications: first, many drug companies are filing citizen petitions as a last-ditch effort just months before generic approval; and, second, many of these citizen petitions may be the last barrier in the way of final generic approval. Put another way, when so many generic applications are approved within six months—the equivalent of 180 days—of when a citizen petition is filed, and the FDA had 180 days to respond to a citizen petition, the relationship does not seem to be mere coincidence. This may also explain why the trend toward late citizen petitions is not as pronounced in the period before the 2007 Amendments: citizen petitions still may have been filed during the late stages of the FDA’s consideration of generic applications, but since the FDA was not held to a specific deadline for responding to citizen petitions, lengthy petition reviews could have pushed back the horizon for final generic approval by more than six months. Delving deeper into this striking correlation between the FDA’s deadline of 180 days and the plurality of citizen petitions filed within 180 days of generic approval would be an interesting avenue for future research.

V. THE ROAD AHEAD

As the results demonstrate, pharmaceutical companies have hijacked the citizen petition process as a route to frustrate generic approvals. We found evidence that many citizen petitions are not filed as soon as potentially worrisome information about a drug is discovered, but are instead filed near the later stages of the generic approval process. Nearly half of potentially delay-related citizen petitions between 2000 and 2012 were filed within a year and a half of approval, with numbers even higher when the data are restricted to the period after the 2007 Amendments. In fact, 46 percent of the post-2007 Amendment citizen petitions were filed within a year of final approval of the generic drug, and 24 percent were filed within six months. These findings suggest that the citizen petitions were some of the last barriers to approval for some generics.

[Page 70]

Looking at the nature of the problem, one could imagine three types of approaches to curb the behavior of filing citizen petitions to delay generic entry. These might include (1) a simple prohibition on competitors filing citizen petitions related to generic entry, if one were to conclude that most behavior represented by this type of petition is likely to be inappropriate; (2) procedural blocks to ensure that the behavior cannot create suboptimal results; or (3) punitive measures as a deterrent. The details of the mechanism are less important, however, than choosing among the pathways and identifying the proper incentive structures and the optimal institutional actors.

No approach is a perfect or permanent solution. Fixing abuse of the citizen petition pathway may require a combination of these approaches. Moreover, in our book "Drug Wars," my colleague and I show that when the legal system closes off one pathway, pharmaceutical companies will search for others. Thus, whatever paths and approaches are chosen to curb citizen petition abuse, it will be critical to ensure that regulators, legislators, and courts can see new techniques as they emerge. A little sunshine goes a long way.

In particular, greater transparency from the FDA could be tremendously effective in exposing new drug pricing schemes early on. Although the FDA makes a wealth of information publicly available, there are significant gaps in the system. For example, as described earlier, there is no systematic way to find the date on which a generic application was filed. Perhaps all generic applications should be posted when filed, along with the date of their filing, and the public should not have to wait until the generic is approved to find that information, if it even appears in the approval letter. As it stands now, the more effective a drug company is at blocking generic competition, the longer that company has before anyone outside the FDA can see what is being done. At the very least, once a generic application has been approved, the public should be able to tell easily when the application was filed. Specifically, all approval letters should be posted on the FDA website, and the FDA website should always list filing and approval dates for every generic, and not only in those letters.

Unfortunately, the FDA appears to be moving in the opposite direction and lessening transparency. For our study, we were able to extract filing dates from some of the approval letters that the FDA posted and backfill many others through our estimation technique when the FDA approval letters did not mention the filing date. The FDA recently changed its protocols, however, so that the public will no longer be able to do even that. According to one report, the FDA has initiated a new protocol in which it will omit from approval letters any mention of the filing date of the original generic application.24

Other basic information could improve transparency as well, including more complete labeling of citizen petitions themselves, and full information on generic application numbers and how they are assigned. Finally, the massive Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) backlog at the FDA also operates to mask improper behavior. When we inquired for our research, Agency personnel were wonderfully helpful, but noted that FOIA requests would require approximately two years for a response.

[Page 71]

Making full data on generic applications quickly and clearly available to the public is essential for curbing inappropriate behavior. Particularly if the FDA is not assigned the full task of policing competition, other actors—including state and federal regulators, legislators, academic researchers, public interest groups, and generics companies themselves—must have easy access to the relevant information. Transparency efforts such as these, along with the types of approaches described here for curbing attempts to delay generic competition through citizen petitions, are essential for addressing the problems. Without such endeavors, we will continue to see a citizen’s process diverted to the service of pharmaceutical companies playing games to hold off generic entry as long as possible. Consumers, of course, would end up paying the price.

[Page 72]

——–

Notes:

1. Harry & Lillian Hastings Professor of Law & Director of the Institute for Innovation Law, University of California Hastings College of the Law.

2. Program Associate, Institute for Innovation Law, University of California Hastings College of the Law.

3. Research Fellow, Institute for Innovation Law, University of California Hastings College of the Law. This piece summarizes a study published in the following works: Robin Feldman & Evan Frondorf, Drug Wars: How Big Pharma Raises Prices and Keeps Generics Off the Market (Cambridge 2017); Robin Feldman, Evan Frondorf, Andrew Cordova, & Connie Wang, Empirical Evidence of Drug Pricing Games: A Citizen’s Pathway Gone Astray, 20 Stan. Tech. L. Rev. 39 (2017). It is published with the permission of Cambridge University Press and the Stanford Technology Law Journal.

4. See Wendy H. Schacht & John R. Thomas, Cong. Res. Serv., Report R41114, The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Quarter Century Later 5, at Summary (2011), https://digital.library.unt.edu/ ark:/67531/metadc816414/m2/1/high_res_d/R41114_2012Mar13.pdf.; see also Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act: Hearing on H.R. 1 Before S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 108th Cong. (2003) (statement of Jon W. Dudas, Deputy under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Deputy Director, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ pkg/CHRG-108shrg91832/html/CHRG-108shrg91832.htm.

5. Cong. Budget Office, How Increased Competition from Generic Drugs Has Affected Prices and Returns in the Pharmaceutical Industry 37 (1998).

6. See Medicine Use and Shifting Costs of Healthcare: A Review of the Use of Medicines in the United States in 2013, IMS Inst. for Healthcare Informatics at 51 (Apr. 2014), https://democrats-oversight. house.gov/sites/democrats.oversight.house.gov/files/documents/IMS-Medicine%20use%20 and/20shifting/20cost/20of/20healthcare.pdf.

7. Implementation of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments of 2012 (GDUFA): Hearing before the H. Comm. on Oversight & Gov’t Reform, 114th Cong. 1 (2016) (statement of Janet Woodcock, Director, Ctr. for Drug Evaluation & Res., U.S. Food & Drug Admin.).

8. See Feldman & Frondorf, supra note 3.

9. See generally id.

10. See Michael A. Carrier & Carl J. Minniti, Citizen Petitions: Long, Late-Filed, and At-Last Denied, 66 Am. U. L. Rev. 305, 333 tbl. 4 (2016), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2832319 (finding that between 2011 and 2015, the FDA denied 92 percent of section 505(q) citizen petitions, the type most often employed to oppose generic entry); Michael A. Carrier & Daryl Wander, Citizen Petitions: An Empirical Study, 34 Cardozo L. Rev. 249, 274 (2012) (finding that the FDA denied 81 percent of all citizen petitions filed by competitors against drug companies between 2001 and 2010).

11. Robin Feldman, Rethinking Patent Law 160 (2012) ("As so often is the case, complexity breeds opportunity, and clever lawyers have been exploiting the details of the act since its inception.").

12. See House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust Concerns and the FDA Approval Process (July 27, 2017) (statement of witness Lietzan, starting at 2:03:45, suggesting that claims rest on "anecdote and rhetoric, not evidence"), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dt2yOVCMFdA&featur e=youtu.be&t=2h49m17s.

13. In rare circumstances, a filing date was available, but not an approval date. This occurred when a drug had only been tentatively approved, but was still posted on the FDA’s website with an attached letter noting the filing date.

14. There were a total of 157 delay-related citizen petitions with filing information (including those with only a filing date and those with both a filing and approval date) and 159 delay-related citizen petitions with approval information (including those with only an approval date and those with both a filing and approval date).

15. The number of citizen petitions filed within six months before generic drug approval was 33 out of a total of 158 petitions (21 percent).

16. FDA Amendments Act of 2007, Pub. L. No. 110-85, 121 Stat. 823 (2007) (codified as amended in scattered sections of 21 U.S.C.).

17. See Carrier & Wander, Citizen Petitions, supra note 10, at 263 (quoting 153 Cong. Rec. 25,047 (2007)) (discussing testimony of Senator Edward Kennedy that "[t]he citizen petition provision is designed to address attempts to derail generic drug approvals. Those attempts, when successful, hurt consumers and the public health").

18. 21 U.S.C. § 355(q)(1)(F) (2015); Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, Pub. L. No. 112-144, 126 Stat. 993 (2012) (codified as amended in scattered sections of 21 U.S.C.).

19. See id.

20. See id.

21. A total of 69 citizen petitions were filed in the period before the 2007 Amendments. Twenty-eight of them (41 percent) were filed within eighteen months of generic drug approval.

22. In the post-2007 Amendments period, we measured a total of 89 citizen petitions relating to generic drug applications with approval dates available. Of those 89 petitions, 50 were filed (56 percent) within eighteen months of generic drug approval.

23. In the post-2007 Amendments period, the number of citizen petitions filed within six months of generic approval was 21 out of a total of 89 petitions (24 percent). The number of citizen petitions filed between six and twelve months of generic approval was 20 out of a total of 89 petitions (22 percent). Our findings are consistent with another study using a different methodology and a smaller sample set of the five years of citizen petitions filed between 2001 and 2015. See Carrier & Minniti, Citizen Petitions, supra note 10, at 338, 339 & Table 8. Ninety-eight percent of these "late-filed" petitions were denied. Id. at 341 & Table 8.

24. See Bob Pollock, Do You Notice Something Missing? What the Heck!, Lachman Consultants (Mar. 31, 2016), www.lachmanconsultants.com/2016/03/do-you-notice-something-missing-what-the-heck/.