Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Fall 2019, Vol 29, No. 2

Content

- Chair's Column

- Compliance With the California Consumer Privacy Act In the Workplace: What Employers Need To Know

- Editor's Note

- Let Me Ride: No Short-cuts In the Antitrust Analysis of Ride Hailing

- Masthead

- Monopsony and Its Impact On Wages and Employment: Past and Future Merger Review

- Protecting Company Confidential Data In a Free Employee Mobility State: What Companies Doing Business In California Need To Know In Light of Recent Decisions and Evolving Workplace Technology

- Social Media Privacy Legislation and Its Implications For Employers and Employees Alike

- The Complexities of Litigating a No-poach Class Claim In the Franchise Context

- Whistleblowing and Criminal Antitrust Cartels: a Primer and Call For Reform

- Competitive Balance In Sports: "Peculiar Economics" Over the Last Thirty Years

COMPETITIVE BALANCE IN SPORTS: "PECULIAR ECONOMICS" OVER THE LAST THIRTY YEARS1

By Daniel A. Rascher, Ph.D. and Andrew D. Schwarz2

In 1984, with its ruling in Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n ("NCAA") v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma,3 the Supreme Court recognized that benefits can accrue to society when potential competitors limit their competition in the interest of competitive balance. In the thirty years that have followed, a period in which professional sports have increasingly become partnerships between owners on the one hand and strong players associations on the other (notwithstanding the recent cultural clashes between owners and players), courts and collective bargaining have mapped out boundaries of acceptable collective action geared around creating competitive balance, all in the name of increasing consumer demand for each sport’s product. Similarly, college sports (though not in a bargaining-based partnership with its players) have relied on the same competitive-balance justification for its collective refusal to pay athletes at market-based rates (in addition to claims that the existence of college sports requires that "athletes must not be paid"4).

However, while the last thirty years have seen competitive balance put forth as a pro-competitive justification, the economic basis for this claim is not quite so clear. In fact, in many cases rules that have been adopted with the express aim of achieving competitive balance have been shown not to do so, while others that do achieve balance may only do so at the expense of consumer preferences. Figuring out which rules truly grow consumer demand is an empirical exercise—there is no one-size-fits-all theoretical answer.

At the professional level, the logic of competitive balance has received a fairly non-critical view, with players associations generally accepting that salary caps, revenue-sharing, and individual player maximums grow the total value of the sport via improved competitive balance, even though many of the mechanisms in question are not based on firm economic theory. In contrast, on the collegiate side, where in the absence of collective bargaining such rules have been challenged in antitrust litigation, courts have been more inclined to look for evidence that the team and individual-player pay caps implicit in "amateurism" actually help competitive balance before simply accepting this economic nostrum as fact. Put to that test, the argument that caps on compensation improve competitive balance has tended to fall flat.

For example, in O’Bannon v. NCAA, a group of men’s college basketball and football players brought an antitrust class action to challenge the NCAA’s restrictions on their ability to earn money from the use of their name, image, and likeness (NIL).5 The district court rejected competitive balance as a procompetitive justification for the naked collusion on athlete remuneration, finding that "the NCAA’s current restrictions on student-athlete compensation do not promote competitive balance."6 The Ninth Circuit concurred.7 In NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid-Cap Antitrust Litigation (a.k.a., "Alston"), a class of major college football and men’s and women’s basketball players challenged the NCAA’s collusive pay restrictions preventing schools from offering more compensation to these athletes for their athletic services.8 In that case, the notion of competitive balance as a procompetitive justification took a back seat, with the defendants (NCAA and the FBS9 conferences) proffering no evidence and thus having this defense ruled out at summary judgment.10

[Page 58]

The analysis below explores whether and when efforts by sports leagues to promote on-the-field competitive balance are in the interests of consumers. First, we show that competitive balance can be an important and pro-competitive objective and outcome of sports leagues, but that the evidence is mixed as to whether consumer demand hinges on balance.11 Second, we discuss the history of league efforts to promote competitive balance. Finally, we analyze the efficacy of two of the rules purporting to affect competitive balance, revenue sharing and salary caps. Along the way we also explore a case study: how would a class of elite athletes demonstrate class-wide harm from an anticompetitive restraint on the commercialization of their NIL and athletic reputation.

I. IMPORTANCE OF COMPETITIVE BALANCE: THE HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS

The on-field dominance by the New York Yankees baseball teams of the 1920s led to attendance problems for the Yankees and for many of the other Major League Baseball (MLB) teams. Fans grew tired of lopsided, predetermined affairs, instead preferring uncertain outcomes and balance.

[Page 59]

In 1964, economist Walter Neale recognized the uniqueness of competitive balance to sports in noting the "peculiar economics of professional sports."12 Neale’s work pointed out that while Coca-Cola may wish that Pepsi would disappear, the Yankees benefit financially when the Oakland A’s13 are of high quality. Thus, the nature of competition was infused with a need for cooperation, which has itself been the core of the argument that sports leagues and their franchises constitute a joint venture or perhaps even a single economic entity.14 In fact, the courts upheld the Commissioner of Major League Baseball’s decision to nullify certain trades in 1976, explicitly based on the notion that athletic competition would be reduced if allowed to be consummated.15

Does competitive balance increase demand? The economic research offers nothing more than an "it depends." Optimal levels of competitive balance can increase demand, but there is a growing body of recent research drawing on behavioral economics showing that competitive balance may often be outweighed by fans’ preference that the home team win or for there being an upset, whether expectations are met and how, or changes in league standings.16 Notwithstanding the many measures of competitive balance (e.g., within-game, game-to-game, within-season, season-to-season17), increased expected closeness of a contest has been shown to increase live gate attendance and television viewership.18 The closeness of winning percentages and total team quality (measured as the sum of winning percentages) has been shown to improve TV viewership while the score at halftime affects the second-half television audience.19 The closer games are expected to be (using both winning percentages and betting odds) and the higher the total quality of the two teams are, live gate attendance is improved as well (when controlling for other factors).20 Analysis of MLB from 1901-1998 shows that attendance is improved with closer standings throughout the season.21

[Page 60]

Twenty years after Walter Neale’s revelation, the Supreme Court in Board of Regents recognized the special economic forces at work in sports leagues, holding that specific NCAA rules (namely the joint sale of television rights), which would otherwise be illegal per se in other industries, needed to be evaluated using the rule of reason weighing the net anti- or pro-competitive effect of the rules in question.22 Fast forward twenty-five years to the more recent American Needle case, where the Supreme Court noted that the legitimate interest in maintaining competitive balance among teams is still subject to the rule of reason.23 Ironically, in both of these cases, though the Supreme Court has enshrined competitive balance as a laudable aim, nevertheless both leagues/sanctioning bodies in question (the NCAA and the National Football League) lost, with the restraint in question found not to be justified because of competitive balance, and in the two more recent cases when the NCAA tried to take advantage of the legal support for competitive balance, it found it could not prove its "amateurism" rules contribute to competitive balance.24

To be clear, the concept of (athletic) competitive balance is pro-competitive (in an economic sense) only when it generates a desired product attribute that enhances the product and increases revenues, although in a rule-of-reason setting, it may have to be weighed against possible anticompetitive effects. As one of this paper’s authors explained in Alston,

"Procompetitive effects" is an economic term of art with specific economic meaning. In that economic context, the term is not a malleable, catch-all phrase, synonymous with socially desirable aims, however laudable those goals may be. To be procompetitive, a restraint must cause increases in overall economic welfare or the reduction in economic exploitation, as economists define those terms. . . . If a restraint causes net improvement to economic welfare according to economic theory and consistent with the results of studying the effects in the market place, a restraint can be characterized as causing "procompetitive effects."25

With many current leagues sharing specific revenue streams with players, it is clear that to the extent there is an optimal level of competitive balance in a given league/sport, it will benefit fans, owners, and players. Where room for debate exists is whether a specific rule actually enhances consumer demand (or even promotes competitive balance at all).

[Page 61]

II. THE EXOGENOUS STRUCTURE OF SPORTS LEAGUES

The notion that competitive balance is a key part of the product that customers of sports demand, and that it is really unique to sports, is essentially what Neale called the "peculiar economics of sports."26 Three critical exogenous27 facets of sports leagues help explain why rules aimed at enhancing competitive balance can be pro-competitive.

A. Competitive Balance Is Exogenous

As noted above, a unique aspect of sports leagues is that the primary product is typically an event (or season culminating in a championship) between two competitors, often two different companies. Yet, cooperation is needed and (some level of) parity is desired by fans. This cooperation and goal of competitive balance causes the members of leagues to create many rules that purportedly affect such balance. These rules are endogenous (e.g., a salary cap), in that they are created internally by league members. Of course, this is also the case with individual athlete sports like golf, tennis, auto racing, or mixed martial arts. Rules are established to create a competitive environment. However, some aspects of sports leagues are essentially exogenous and occur because of market forces.

Demand for competitive balance itself is exogenous to a league. Customers demand some level of balance (or not) to make the product exciting. Leagues have to figure out how to maintain an optimal level of competitive balance, but that is because the market demands it rather than because balance is inherently superior to imbalance. The nature of needing two teams to play each other, or six or more teams to form a minimally suitable league, or eighty golfers to play a tournament, automatically causes consolidation compared with other industries where competition across different firms occurs without any need to coordination. For example, Nike and adidas do not need each other for success, nor do they want each other to be formidable competitors. Yet, the Yankees need the A’s to be decent enough to create competitive games and seasons.

B. The Market Demands That the Best Play Against the Best

In many aspects, demand for a single league or circuit may be an exogenous factor driven by fans’ desire to see the best athletes and teams competing with and against each other in the same game, event, or season. Imagine if Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova had never played against each other because they were on different tennis circuits, or Jack Nicklaus did not compete against Arnold Palmer, or Jerry Rice did not catch touchdowns from Joe Montana, or Magic Johnson did not compete against Larry Bird. The market seems to demand that the best play against/with the best. This drives the long-run equilibrium toward single-sport leagues,28 so that the single-sport provider is often a natural outcome of the nature of sports.

[Page 62]

However, there are more competitive means to meet this demand rather than simply merging competitive leagues into a monopoly, such as when otherwise competing leagues agree to face off in a common championship. Such an arrangement allows the major European soccer leagues to crown separate champions who then face off against each other (and other major teams) in the UEFA Champions league. In some sense, both the World Series and the Super Bowl began as similar two-league championships, but in both cases the leagues soon merged (in the case of the National Football League (NFL) and American Football League (AFL)) or at least stopped competing for talent (in the case of the National League and American League, which only formally merged in the 1990s29) even if they remained legally distinct.

In other sports, though, multiple parallel leagues can exist and thrive. For example, in mixed martial arts (MMA), while the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) has been a consistent leader in the sport, Bellator and the Professional Fighters League (formerly the World Series of Fighting (WSOF)) compete with UFC. Recently, an Asia-based competitor, One Championship, announced its intent to enter the market as well, signing a broadcast deal with Turner Network Television (TNT).30 Whether this sport needs a single league or other ways to ensure the best can compete against the best remains to be worked out.

Additionally, having many leagues (or many teams within a league) "reduces the absolute quality of play. From the perspective of the fans, some restrictions on the number of leagues in a sport and teams within a league may be socially desirable."31 Research shows that too many leagues in baseball led to a decrease in the quality of play overall and a decline in demand.32 Specifically, "adequate control of external effects associated with quality will be achieved only if there is but one league in a sport."33 In other words, not only do fans desire to see the best play with/against the best, but multiple leagues also tend to dilute the existing talent base. Thus, sports can differ from most other industries, where having many providers generally leads to higher quality, more innovative products, and lower prices, all of which benefit customers. Similar to sports, there are joint ventures in other industries (e.g., biotech) that can lead to better products and distribution. Yet in sports, while customers would like lower prices (which may not be forthcoming when there are single providers of a sport instead of multiple competitors), they do not want diluted talent and do want the best to play against/with each other.

In college sports, there has been a historical evolution (within the NCAA) from schools within leagues playing each other without regard for a specific or defined level of play (i.e., MLB compared to minor league baseball). After decades of undivided competition, the NCAA organized leagues as either at the university or college level, followed by a disaggregation of schools into Division I, II, or III. Even within Division I, there remained vast differences in commitments to major spectator-driven college sports. It therefore further separated into Division IA (schools offering major college football, now called FBS), Division IAA (schools offering a level just below IA in terms of football, now called FCS, but still playing at the same level in other sports), and Division IAAA (schools playing Division I sports, but not offering football). And finally, Division IA has further separated into the Power Five conferences and the Group of Five conferences, with the former now governed by a special set of somewhat more permissive five-conference rules, inaccurately referred to as "autonomy." The talent base has tended to follow this pattern with the most coveted athletes choosing FBS schools. Consequently, despite the (increasingly disproven) claim that capping college athlete pay improves competitive balance, we see college sports recruiting—especially in football and men’s and women’s basketball—dominated by an elite subset of teams. Rather than spreading out talent, the college caps seem to cement existing imbalance.34

[Page 63]

One of this paper’s authors is in the process of launching a professional college basketball league—the Historical Basketball League (HBL)35—with the goal of hiring a large portion of the top 150 athletes in each class entering college. The aim would be to provide fans with the ability to see the best playing with and against each other every night of the season, rather than waiting for an end-of-season tournament in March. If HBL is a success, it will be the NCAA’s pay caps that led to, rather than prevented, this new league’s dominance.

C. Sports Leagues and Teams Compete with Other Forms of Entertainment

The NFL is the single provider of major professional football in the U.S. (notwithstanding the recently failed Alliance of American Football (AAF) and the second attempt at the XFL, launching in summer 2020). Is it a monopolist, whether or not a "natural" one? That question hinges on whether the NFL competes in a larger product (or geographic) market that contains other entities. The jury in USFL v. NFL found that the "NFL had willfully acquired or maintained monopoly power in a market consisting of major-league professional football in the United States," but "the NFL had neither monopolized a relevant television submarket nor attempted to do so."36 While some point to this as a confused verdict, it may in fact reflect the view that while the NFL is the dominant (or only) provider of professional football, by itself that does not mean there is a specific television market in which only the NFL (and erstwhile rivals such as the USFL or XFL) compete.37 This is because sports are really multi-product bundles. The Los Angeles Dodgers (baseball) and Los Angeles Rams (football) might compete for ticket sales (at least when their seasons overlap in September), but the Dodgers and Chicago Cubs (baseball) almost surely do not. In contrast, the Dodgers and Cubs do compete for free agents and as on that dimension are much closer competitors to each other than either is to the Rams. At the same time, though it would need to be shown empirically, all three might compete in a national market for jersey sales, though it is doubtful sports jersey compete with unbranded sweatshirts in some broader apparel market.

[Page 64]

Importantly, in the context of antitrust, economic competition is a term of art, based on the economic concept of cross-price elasticity of demand. What matters is not whether a family’s choice to attend an SF Giants game means there is no room in the household budget, or time in a particular week, to also attend a San Jose Sharks game, but rather whether in aggregate, the quantity of tickets bought for Sharks games varies appreciably with changes in Giants’ ticket prices.38 This means that intuition about overlapping seasons, etc., can only go so far in answering the economic question in a rigorous way. As such, many courts have found that there do exist distinct relevant markets in single sports.39

With that said, there is burgeoning academic research, and existing industry anecdotal research, showing that sports leagues compete with other forms of sports entertainment at least with respect to key outputs such as merchandise, licensing, and television broadcasts.40 For example, when the National Hockey League (NHL) cancelled an entire season, NBA and minor league hockey both experienced boosts in attendance.41 An older study estimated that average NHL per game live attendance was nearly 20% lower in the ‘average’ city with three other professional sports teams and that inter-sport competition reduces MLB season live attendance by 250,000 (21%) in the ‘average’ baseball city.42 Other research suggests that the closer two teams are geographically, the lower attendance is at each team relative to two teams that are farther apart.43 What has yet to be shown in a definitive way is whether moderate changes in the ticket prices of one sport’s team has quantifiable impact on the quantity of tickets sold for other sports.44

[Page 65]

There is overlapping fan support across sports; e.g., some Cincinnati Bengals season ticketholders likely also attend Cincinnati Reds games. Accordingly, adding a team to a market does have an impact on teams in other sports in that same market. For example, after the Nationals came to Washington D.C. in 2005, the Washington Wizards of the NBA saw a decline in attendance by 5% (for the two years prior and post-relocation), even though the Wizards improved its record by 40%.45 The Washington Capitals also saw a 9% decline in attendance for the two years before and after the Nationals moved to Washington D.C., but this may be related to decreased on-the-ice scoring or the 2004 NHL work stoppage.46 But now that the Nationals are established in the marketplace, it remains an open question how much their ticket prices influence changes in consumption of Wizards or Capitals games.

While general tickets findings are mixed, luxury suites clearly show a form of cross-sport competition, and the effect can be seen not just in attendance but in price. Data from the Association of Luxury Suite Directors show that luxury suite prices are highly dependent upon the number of other sports facilities with luxury suites available in the marketplace.47 The Capitals and Wizards had luxury suite prices that were above the average by 17% for combined NBA/NHL arenas in 2001.48 In 2007 (after the Nationals had moved to Washington D.C.), the luxury suite prices were about 5% lower than the same group.49 This provides evidence that there exists competition at the luxury suite level across the major sports leagues in the U.S., suggesting that to these customers, a luxury suite in any one sport may indeed be a good substitute for any other sport, if the goal is simply a luxurious suite for entertaining clients. Studies have generally supported the twin ideas that within common geographic regions, teams both within a given sports league and across sports leagues compete with each other, albeit with the economic effects being relatively small.50

[Page 67]

It is perhaps more evident that companies interested in sponsoring sports teams, leagues, events, and athletes can search for sponsorship opportunities in a competitive market. Not only is sponsorship but one of many forms of marketing, but there are many franchises, facilities, leagues, and events, with which one can partner. There is generally a media frenzy when the media rights to the NFL, for instance, are put into the marketplace. Bidding occurs across the major networks (ABC/ESPN, CBS, NBC, and FOX), with potential new bidders among the major social media, digital media, and ecommerce companies (Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, etc.). A network that does not end up with the rights certainly finds a cost-effective way to fill those hours of programming. The NBA, NHL, and MLB appear on many different cable outlets (e.g., TBS, TNT, NBC Sports) as well as the major networks. Historically, when NBC has not won the rights to show NFL games, it has instead focused on the Olympics, horse racing, golf, and tennis. When CBS was the "odd man out" in showing NFL games (prior to regaining an NFL contract in 1998), it offered more college basketball programming. Now, the NFL is contracted with each of the big four broadcasters, earning $6 billion per year from Fox, CBS, NBC, and ESPN (ABC), and also with DirecTV. NBC has also continued with the Olympics, paying over $7 billion to air the Olympics through 2032. The leagues also have Turner Sports as a competitor for their rights, as Turner-owned TNT and TBS show the NBA and MLB, respectively.

[Page 68]

Even though fans may generally want a single league to watch the best athletes play with/against each other, rival sports compete against each other on at least some dimensions. Thus, while it is in each league’s interest to maximize its revenues by enhancing consumer demand for each sport (and thus leagues aim for competitive balance), the revenue-maximizing level of competitive balance is not necessarily an equilibrium that would occur on its own. Therefore, unlike in other industries, in sports rules are seen as needed to maintain competitive balance, such as salary caps, revenue sharing (to be discussed below), and limits to the number of teams in a league. Attempts to break up the nationwide professional leagues to achieve competitive balance through competition won’t necessarily be socially beneficial unless fans (i.e., consumers) feel that ultimately the question of who is best is decided on the field.51 But to the extent that alternative inter-league championships can be developed, multi-league competition might achieve better, more balanced (athletic) competition along with more intense (economic) competition.

III. THE RULES THAT SPORTS LEAGUES USE TO MAINTAIN COMPETITIVE BALANCE

In response to the perceived need to maintain competitive balance, sports leagues have developed numerous rules such as salary caps, revenue sharing, amateur draft, no-cash trades, and the reserve clause or player restrictions. Here, we focus on the history and economics of two rules that are most often heralded as the solution to competitive balance problems: salary caps and revenue sharing.

A. Team Salary Caps and Floors

In response to concerns about free agency’s potential impact on competitive balance, professional sports leagues and their union counterparts have agreed upon maximum aggregate payroll limits (known as salary caps) for each team, on the theory that without such caps, large-market teams (or those owned by win-maximizing owners) might "overspend" and destroy competitive balance.52 Analogously, some leagues have also added a salary floor, i.e., a minimum aggregate payroll for each team. Although much less commonly discussed in the general sports media, salary floors are generally more important for ensuring competitive balance than are salary caps (or revenue sharing, which is discussed below). This is because it is often privately optimal for small market teams to spend far less than their large-market counterparts, even if those teams are subsidized through revenue sharing. A salary floor ensures that teams spend shared money on talent, rather than pocketing it as profit. In the NFL for instance, player salaries have long been guaranteed to hover around 50 percent of revenues,53 but this was not always the case.

In 1987, immediately after the end of a failed players’ strike that resulted in the league and players operating without a collective bargaining agreement, the National Football League Players Association (NFLPA) sued the NFL over rules limiting free agency as being anticompetitive.54 In Powell v. NFL,55 the Eighth Circuit of Appeals reversed the players’ initial victory on partial summary judgment and ruled that although the collective bargaining agreement had expired, the existence of the NFLPA as a union provided the NFL with immunity from antitrust suits.56 In response, the NFLPA decertified itself as a union and sued again, this time with Freeman McNeil as the plaintiff. 57 When this case (and a follow-up class action led by Reggie White58) went the players’ way, the ultimate settlement led to a re-certification of the NFLPA and a collective bargaining agreement that allowed free agency.59 At the same time, the parties recognized the possibility that free agency might harm competitive balance, and so the new collective bargaining agreement included a salary cap and a salary floor to ensure all teams’ payrolls fell within a common range.60

[Page 69]

Thus, in the NFL, the salary floor has existed since the same 1993 collective bargaining agreement (CBA) that also ushered in the more famous salary cap. Article XXIV of that CBA ("Guaranteed League-Wide Salary, Salary Cap and Minimum Team Salary") set up formulaic rules for both the cap and the floor.61 The salary cap for each season is a function of the upcoming season’s expected average league revenue. Per the 1993 agreement, the salary cap rules attempted to limit each team’s total player salaries to approximately 63 percent of the average team’s defined gross revenues (DGR), while it could not go below 50 percent of DGR.62 This 1993 agreement was renewed several times until a new CBA was signed for the 2006 season, in which the floor was set to 84% of the cap, increasing by 1.2 percentage points per year, so that it would have reached 90% by 2011 had the owners not exercised their option to end that CBA in 2010.63 After a lockout that threatened to delay the 2011 season, the CBA that followed set the NFL salary cap at $120.375 million per team, and the team salary minimum at 89% of that upper bound, climbing to 95% of the upper bound for the last few years of the deal.64 The players are also guaranteed a league-wide share no less than 47% of total league revenues. That CBA is set to expire in March 2021. The players and league have already been meeting regularly, but none of the purported issues on the table would appear to affect competitive balance.65

[Page 70]

Salary restrictions that include both caps and floors are the most effective method for maintaining or improving competitive balance because this forces teams to spend similar amounts on player payrolls. Otherwise—and this cannot be stressed enough—revenue sharing to small-market teams is unlikely, by itself, to induce the small-market team to spend more. Without a salary floor, a team spending at the optimum small-market level does not see any reason to spend even one dollar of any additional revenue it gets from other teams’ actions. On the other hand, a salary floor creates a constraint that changes the optimum pay level for those small market teams (to the minimum, which is higher than the unconstrained optimum). Thus, while a binding salary maximum puts a restriction on the average salary of a player, and thus decreases the wage per unit of talent, the salary minimum effectively raises the pay per unit of talent, if the floor is binding, by pushing up small-market pay levels.

However, a further result is that revenues for some large market teams may decrease because they are forced to field less talented teams than would otherwise be the case. The opposite may occur for small market teams—namely, the team might produce quality in excess of the optimal level associated with maximum profit for the league. By itself, these two will not cancel out, since both small and large market teams have moved to a suboptimal level of pay, so aggregate revenues will shrink. However, the decline in overall league revenues is likely to be smaller than the decrease in salaries, thus increasing profits for each team and the league as a whole.66 Moreover, competition across sports (especially in markets like sponsorship where sport-specific factors matter less) helps to ensure against extreme degradation in overall quality.

Similarly, salary caps keep the pay of the best players below what a free agent system would pay them. However, team payroll minimums and individual player salary minimums (players earning the league minimum) actually raise some players’ salaries above what an open market would pay. In fact, almost 50% of players in the NFL earn the league minimum.67 If the league were to have moved (via a successful Brady68 lawsuit by the players) to a complete free agent system, some players likely would have gained and some likely would have lost.69 Further, if league revenues are maximized with more competitive balance, and if an open system would have led to less balance, then the marginal revenue product (MRP) of NFL players on average would have likely declined because total revenues would have declined.70 When MRPs decrease, so does the amount that teams can gain from players, hence their pay is lower.71 This is ultimately an empirical question.

[Page 71]

It is worth noting here that the same logic does not necessarily apply in a sport where there is a player maximum but not a player minimum, such as the college version of football. There, the raising of the cap has no theoretical impact on compensation for athletes at the bottom of the talent pool, unless somehow the increase in pay to stars reduces the MRP of other athletes. This is important to keep in mind, as the layperson’s notion "the money has to come from somewhere"72 is not what drives the potential for downward pay pressure in a move from a CBA outcome to a more open market outcome. Instead, it is the potential for salary floors to be removed, and for the figurative bottom to drop out of the market for marginal talent.

Recognize that in college sports, the compensation limits (which are essentially individual and team "salary" caps) are in some ways more complex than in unionized sports. First, each athlete faces an individual cap, with compensation limited to the full cost of attendance ("COA"), plus ancillary bonuses that can reach up to the tens of thousands per year for star performers. But then each team also faces a total "salary" cap, equal to a certain number of scholarships multiplied by the individual cap. In FBS football, this cap is 85 times the individual cap, whereas in FCS it is 63 times the cap. In other sports, like men’s volleyball, the total "salary" cap is so low, at 4.5 times the individual cap, such that it is impossible to pay all six athletes on the starting team the individual maximum. This limit on scholarships is not a roster limit, meaning that essentially, in addition to the limited number of compensated athletes, a team may also take on a large number of "walk ons," which is the term of art for athletes who face a $0 individual cap.

Recent litigation has played a key role in driving up the individual cap level for athletes. O’Bannon established that a cap below the full cost of attendance was "patently and inexplicably" unreasonable, even under an "amateurism" defense.73 Alston, went further, showing that since athletic bonuses in the tens of thousands of dollars are being paid today without harm to demand, caps on academic bonuses at lower amounts are also unreasonable.74 To date, though, the NCAA team "salary" caps, in the forms of limits on the number of such scholarships that can be offered, have remained in place, even though economically, the justifications for limiting quantity are even less valid than those for capping individual "salary." Specifically, they hinge almost entirely on unproven and theoretically dubious claims that limiting the number of scholarships offers improved competitive balance.75 But as anyone who follows women’s basketball can attest, limiting a women’s basketball team to 15 scholarships has done nothing to distribute UConn’s talent across the 350 or so D1 schools.

[Page 72]

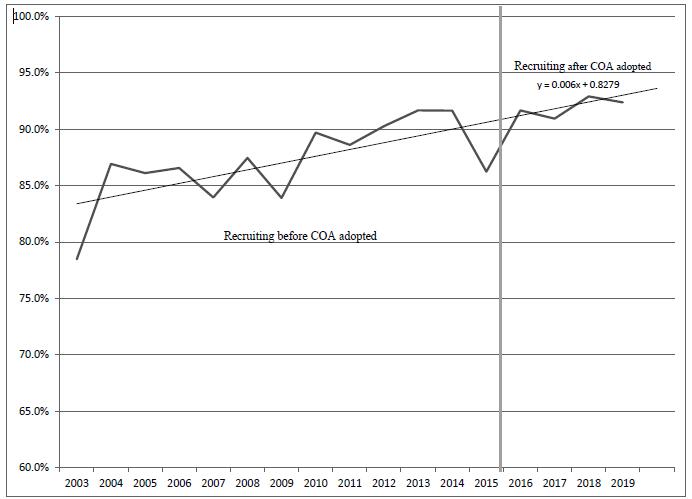

Empirically, there is little doubt that capping the number or value of scholarships is not creating a balanced recruiting field. Consider the year-to-year annual recruiting success of major FBS football programs, based on the rankings of incoming athletes. In a world with competitive recruiting balance, there should be little or no correlation between recruiting a good class in year 1 and doing so again in year 2. Instead, in college football, the correlation is nearly perfect (converging on 100%), and has gotten stronger over time (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Competitive Imbalance in FBS Football, 2003-2019

Image description added by Fastcase.

The year over year success in recruiting goes a long way to (a) explain the persistent dominance of a few schools, notably Clemson and Alabama, in the CFP, and (b) to demolish the myth that capping pay, or limiting scholarship availability, ensure that UMass and Wake Forest can compete for national championships in football every year.

[Page 73]

Outside of the NCAA context, for many leagues, the caps are often not particularly binding, given all of the exceptions and ways of going above the cap (known as a "soft cap").76 In the NBA, during the 2010-11 season, it is estimated that only six teams were actually at or below the salary cap,77 resulting in the seemingly paradoxical result that the average team payroll in the NBA during 2010-11 season was $67 million in spite of a salary cap of only $58 million. Even in 2005 in the NFL with a stricter salary cap, nine teams had payrolls above the cap.78

It is much clearer that team salary minimums help maintain or improve competitive balance. They prevent "free riders" from paying very low payrolls, and thus making money from shared revenues and the brand in general. Free riding is a problem in the NBA, MLB, and the NFL.79 The potential for this free-riding is well understood by players, and ensuring a true floor was a guiding principle in the NFLPA’s 2011 negotiations80:

"We cannot have teams like KC spend only 67% of the cap like they did in 2009," Saints quarterback Drew Brees wrote in an e-mail to his teammates. "It doesn’t matter how high the cap is if they are only going to spend that much. So with a minimum in place, it requires all teams to be at or above that minimum. More money in players’ pockets."

What is clear is that payrolls are more balanced in the NFL compared to other major professional leagues and that competitive balance is greater than in the NFL other leagues. Noll (1988) concludes that salary caps are sufficient to achieve the goal of equal parity and that revenue sharing has no effect (more on this below).81 However, for owners who care more about winning than profits, revenue sharing and salary caps have an indeterminate effect depending on whether sportsmen owners (who want to win, even if winning is not optimally profitable) are in small or large markets.82 The lesson to be drawn may be that the NFL leads the way in competitive balance because of the stricter floor, rather than the existence of the ceiling (although the ceiling is considered stricter than in the NBA).83

[Page 74]

B. Revenue Sharing

Another key tool in leagues’ public pursuit of competitive balance is revenue sharing, which involves the sharing of pooled revenues disproportionately to the source of those revenues. Typically, league-wide television contracts are shared equally among all teams even when certain teams drive far more of consumer demand than others. Such revenue sharing has been part of the fabric of the NFL since the first NFL national television contract was negotiated in 19 62.84 While revenue sharing prevents the lowest revenue-generating teams from becoming insolvent, it also causes a "free rider" problem in which a team may enhance profits by fielding relatively less-talented players to keep costs down, while reaping large profits from sharing revenues with the rest of the league.

In more extreme forms of revenue sharing, leagues can share purely local revenues as well. But the greater the revenue sharing, the lower the incentive to invest in quality since dividing revenues dilutes the rewards of any team’s investments. This creates a dilemma, and a theoretical question: will the benefits of a more evenly pooled revenue raise or lower league quality? To understand this dilemma, one needs to unpack the impact of revenue sharing on leagues’ spending incentives.

First and foremost, revenue sharing lowers the wage paid to players, simply because revenue sharing lowers the return to each team on investments in talent. Revenue sharing decreases the incentive to outbid other teams for a talented player given that part of the financial return on that player will be shared with the league. If a team determines that a certain wide receiver is worth $10 million to the team because that is how much that player can generate in extra revenues (due to increased winning leading to higher attendance, merchandise, and concessions sales), then normally that team would be willing to pay up to $10 million to hire that player.85 Yet, if the team had to share its revenue, say 40% of the gross gains in revenue, then the player would only be worth $6 million once the sharing is netted out. In this case the team would not bid as high for the player, therefore lowering his salary.

The key driver of this result is the fact that only revenues are shared among owners, rather than both revenues and costs. Taken to the extreme, if 100% of revenues were shared, an owner would never reap any team-specific rewards from signing a better player and the labor market for talent would dry up. In Silverman, Judge Sotomayor recognized this effect, noting that it was not simply a harmless exchange of dollars between owners.86 Her ruling prevented the owners from unilaterally imposing revenue sharing rules without the consent of the players association.

While in theory revenue sharing saps profit-maximizing teams’ desire to compete, not all decisions by sports teams are driven by a pure profit motive. Winning matters too. Although NFL owners have to share their revenues, they don’t share their wins or Super Bowl rings. Thus, to the extent that owners care about winning above and beyond their ability to generate profits and are willing to make less money (or even lose it) in order to win, they might be willing to pay more for players than they are "worth" in terms of MRP, due to the dampening effect that revenue sharing plays on the relationship between winning and revenue (and thus profit).

[Page 75]

Secondly, it is not clear that revenue sharing actually changes the incentive of teams in less lucrative markets to spend on the quality needed to achieve competitive balance. The popular notion is that small-market teams will use the net excess revenue that they receive from large-market teams through the national media and licensing contracts and through gate sharing to improve the quality of their teams. In Bulls II, the NBA’s justification for its restriction of the Chicago Bulls broadcasts was the need to maintain competitive balance.87

However, it has been theorized that in equilibrium, an athlete will play for the team for which he or she generates the most revenue, regardless of who owns the rights to that revenue.88 Under this theory, small market teams without a mandatory salary minimum will simply pocket their portions of shared revenue as profit, leaving unsolved the "small-market problem" which plagues some sports. If small-market teams are currently choosing the optimal talent level, a transfer of cash will, by itself, provide no incentive for investments in individually sub-optimally high levels of quality. In fact, most owners have enough access to capital to increase their payrolls substantially. Yet, they choose to remain at some level that they have determined makes the most sense for them. Getting an extra $10 million from the league office does not change anything—they should put it to wherever it is most valuable in their life.89 Revenue sharing along with a salary cap may make the middle more like the top, but the lower third may remain persistent (albeit profitable) cellar-dwellers. Hence the importance, as discussed above, of combining a salary floor with any revenue sharing arrangement.

This is not merely a theoretical concern. Numerous popular press articles detailed how MLB teams that were recipients of revenue sharing money (and also luxury tax sharing, another form of revenue pooling similar to pure revenue sharing) were pocketing the money instead of spending it on players to improve the talent of the team.90 For instance, a year after MLB’s luxury tax/revenue sharing plan was implemented, the Milwaukee Brewers received the most revenue sharing money (about $8.2 million), but it also lowered its payroll from about $50 million to $40 million. In other words, the team may have directly used the money to purchase better players, but any such spending was more than offset when the team lowered its base payroll down to $32 million (so adding the $8 million brought it up to $40 million) rather than adding the money on top of their previous $50 million level.91

[Page 76]

On the other hand, research shows that revenue sharing can improve competitive balance if some owners care about winning.92 A non-disputed finding is that revenue sharing can prevent some clubs from folding, which would, of course, have an effect on competitive balance, since if teams exit small markets, small market teams can’t possibly win.93

Combining these two effects, the third effect of revenue sharing is that profits increase as the incentive to pay players declines, as long as the league in question does not face serious competition from another league in the same sport. That is, if the distribution of talent is not strongly influenced by revenue sharing but the incentive to spend on talent declines, as long as no rival league can scoop up talent on the cheap, team owners will keep a large share of a relatively unchanged pie.

Fourth, unless the revenue-sharing and salary-cap rules are airtight, the fact that some revenues or costs are shared/regulated by the league but not others can create perverse incentives for owners to generate revenue from sources that are excluded from revenue sharing (e.g. stadium revenues). Similarly, owners would also have incentives to incur costs on inefficient revenue generators if those costs are uncapped. Hence an owner may invest in stadium improvements simply because that spending is uncapped and he or she gets to keep all of the return on that investment, as opposed to investing in a new team logo from which any new revenues from national merchandising would be shared with the rest of the league. One example from the NFL is luxury suites, which remained outside of the revenue sharing/salary cap structure until the most recent CBA. This loophole then played an outsized role in the race to build new football facilities with posh and plentiful luxury suites. The new CBA in the NFL applies the salary cap to all revenues, with additional supplemental revenue sharing among owners. The players want the small market teams to have enough funds to meet the team payroll minimum, but another beneficiary may be cities who might face less pressure to build ever-more-luxurious suites to stave off threat for their football teams to leave town. Counting a broader range of revenue sources in the revenue sharing (and salary cap) formula seems to be a trend in major U.S. sports, which should work to eliminate some of these perverse incentives towards suboptimal revenue sources.

[Page 77]

The most egregious example of the perverse incentives of salary caps and revenue sharing comes from college sports. Within most major athletic conferences (e.g. the Big 10 or SEC), revenues from media rights, postseason play, and NCAA sources like March Madness shared equally, other than comparatively small distributions to cover a portion of team’s expenses for post-season play. This means that for a lower-revenue school within a conference, shared revenues make up a substantial portion of an individual school’s revenues, whereas for the powerhouse schools within a conference, unshared revenues sources such as ticket sales and donations, comprise a much larger share of the pie. Combined with the finding that donations may be driven by winning,94 this would normally create an incentive for the strongest schools in a given conference, say Alabama in the SEC or Ohio State in the Big Ten, to spend more on player salary. However, the strict salary cap in college football (where players can receive cash compensation of no more than approximately $7,000 in additional to a scholarship) shifts this desire to invest in quality towards less efficient means. This creates a strong incentive for the Alabamas and Clemsons of a conference to spend far more on facilities than, say, a Mississippi State or a Wake Forest. Despite this incentive for schools at the top of the conferences, overall spending is far more balanced within a conference than across conferences, given the fact that shared revenue tends to dominate.

IV. WHETHER A RULE ENHANCES CONSUMER DEMAND IS AN EMPIRICAL QUESTION

The issue of whether the rules that leagues use to maintain competitive balance are pro- or anti-competitive is ultimately answered both by theoretical and empirical economics. While theory can illuminate the issue, ultimately some form of testing how these rules impact markets may also be necessary to know the impact on sports leagues, sanctioning bodies, athletes, suppliers, and buyers. Economic analysis plays an important role in understanding the special structure and economic forces inherent in sports and in analyzing the competitiveness of league conduct. Allegations of wrongdoing need to be viewed through the correct economic prism before a proper evaluation can occur. This analysis requires an understanding of the exogenous factors inherent in sports leagues, and the rules that leagues use to affect competitive balance, as well as careful study of the specifics of a given rule and how its nuances affect the market in question.

Hence, while the economic factors that sports leagues control, e.g., revenue sharing and team salary restrictions, may superficially appear to be anticompetitive—and even be anticompetitive along one dimension—they nevertheless could promote sufficient growth in revenue because their net impact on competitive balance is pro-competitive. On the other hand, restrictions designed to address competitive balance may merely lower average cost without improving competitive balance and may have unintended side effects as teams’ and leagues’ incentives diverge. In a nut shell, this is the reason why the economics of sports restraints typically fall within a rule of reason analysis, because the answer is almost always "it depends." Policy decisions made without the proper understanding of this crucial fact—that the economics of competitive balance is not as clear cut as sports leagues often claim—may prove to be detrimental to consumer welfare.

[Page 78]

V. CAN ECONOMICS MEASURE THE ANTICOMPETITIVE IMPACT OF SALARY LIMITS?

In the context of a rule of reason antitrust case related to competitive balance measures, a key question is whether economic models can be used to predict what individual athletes would receive in payment in a world with less restrictive rules. For example, in O’Bannon, class certification was denied to the damages class (but granted for injunctive relief) over the court’s concern with a model that did not account for the possibility that individual athletes at the low-end of the talent spectrum might have benefitted from restrictions on payments to more talented athletes.95 But in the interim, economists have moved away from old-style ex post models of productivity, where value can only be predicted after the athlete has performed his/her services, to ex ante models that better align with how compensation offers would work in a marketplace. Unlike ex post models that can sometimes show the result that schools are consistently making irrational scholarship offers, models based on athletes’ ex ante ratings generates econometric results that comport with schools’ revealed preferences. They provide for ways to identify a class of athletes who could allege and prove classwide common impact and model forgone licensing revenues using a common formula, solving the issues raised in O’Bannon by showing that each class member would have earned more than the current limits. And given that the NCAA itself may soon acknowledge that some forms of NIL payments are not demand-decreasing, one can easily imagine a hypothetical class action needing such a model to prove their forgone NIL payments for the four years prior to the lifting of the zero-dollar cap on NIL.

Consider the following hypothetical class: male athletes who entered Division 1 basketball in the four years prior to the NCAA finally allowing for athletes to earn some form of revenue from their NIL and athletic reputations, who were also ranked by a major college recruiting service with three stars or more.96 Further assume that in this new NCAA model, athletes can either choose to market their NIL on their own, or to partner with their schools to jointly market the schools’ intellectual property (IP) along with that of the athletes. In this world, athletes will choose between these two models (self-marketing or joining with a school) on an ex ante basis—that is, prior to the athlete enrolling in college—and schools will thus base their competitive offer on an assessment of the value of adding that athlete to the schools’ IP portfolio. Athletes who see their individual value exceeding a schools’ offer would choose not to jointly market; athletes who do not will sign up. Thus assessing the ex ante value of the athletes’ IP to the schools’ portfolio establishes a lower bound for forgone revenues. In other words, being able to model each athlete’s expected contribution to school revenue97 essentially establishes a base level of damages experienced by each athlete.

[Page 79]

Such a model exists in the sports economics literature. Using data from 2008-2017, Rascher et al. (2019) develop multiple models of college basketball player value to specific schools utilizing what is known in the labor market during recruiting, i.e., their ranking by high school athlete rating services, athletic conference specific effects, and year.98 Team revenues and winning percentage are also utilized to establish the relationship between winning and revenue. These models all show that above-average and star men’s basketball players statistically significantly improve the revenue generated by their programs by hundreds of thousands of dollars and in some cases millions of dollars per year. These models also allow for individual athlete valuations.

With such a model, each athlete who had been recruited prior to the relaxation of the NCAA’s rules could establish his own ex ante value to the team he ultimately chose. Thus each athlete could: (a) establish his antitrust injury (the fact that he was paid zero for his NIL when his but-for value exceeds zero); and (b) establish his own damages (based on that difference). The identical formula could be used for each such athlete, making it amendable to class certification.

VI. THE FUTURE OF COMPETITIVE BALANCE: WHAT WILL THE WORLD LOOK LIKE IN 2050?

One aspect of the NFL’s efforts to achieve competitive balance is a scheduling method called unbalanced scheduling, where teams that do well in a given season are matched against better competition in the following year. This allows for more marquee matchups. It also allows the worst performing teams to play each other more often, providing those teams’ fans with the hope of winning more games. In contrast, for the portion of the college football season in the control of individual schools, college football usually does the opposite—powerhouse schools pay weaker teams to offer themselves up as sacrificial lambs and generate incremental revenues for the smaller school.99 In large part, this is a function of perverse incentives in college football’s current post-season, where losses, even to quality opponents, are punished much more than "cupcake" wins.

[Page 80]

However, now that there is the CFP (a playoff in major college football, albeit with only 4 teams, though widely believed to eventually grow to eight), college football seems to be recognizing the benefits of more competitive balance in the early portion of the season, with the result being that schools are scheduling better non-conference games. At the same time, as the NCAA’s compensation limits have been forced to change with each new legal challenge, each new set of rules further tests the idea that pay caps affect balance, and in each case, no evidence has emerged of greater imbalance. As just one example, first dozens and now hundreds of D1 schools have adopted COA payments, but there has been no notably change in the FBS football or D1 basketball pecking order.

The NFL has led the charge in its focus on competitive balance, but the other major sports are addressing it too. Using the Noll-Scully100 measure of competitive balance, MLB had improved balance in 2014-17 than it had during the prior six years. However, the imbalance it shot up in 2018, mostly driven by the AL’s lack of balance that year. It looks as if the big-spending teams are continuing to spend even more, despite the luxury taxes being paid. It remains to be seen if that level of increase spending makes sense or whether the big-spenders will need to come back to pack. In the next five to ten years, MLB should see improved competitive balance because revenue sharing recipients will find it more difficult to avoid using their additional funds to improve their on-the-field product, and large market clubs will be exempt from being recipients of revenue sharing money. MLB owners and players alike recognize the need to grow baseball’s fan base, both domestically and internationally. The Industry Growth Fund coming from luxury taxes will help, as will the growth of the Australian Baseball League and domestic leagues in other countries. The World Baseball Classic should help speed up the growth of baseball worldwide, which will position MLB as the premier league for a new generation of fans.101 These issues, while relatively uncontroversial, will be a focus in future CBAs.

To the extent competitive balance is critical for consumer demand, the need for competitive balance will only be enhanced as sports increasingly compete against each other for domestic and international viewership. Increasingly, soccer, especially the English Premier League, is programmed against major American sports as networks without football or basketball (especially new cable channels dedicated solely to sports) look for new ways to attract viewers to live sports. At the same time, the growing international popularity of American sports, will likely lead to overseas expansion, with perhaps the NBA having multiple teams in Europe within the next two decades.102 As sports across the globe are pitted against each other for viewers and fans, each league may be tempted to emphasize those rules that enhance consumer demand for its sport, and efforts to optimize competitive balance will be in the forefront of that movement. What remains to be seen is whether a foreign league with strong competitive balance has higher or lower demand than a foreign league with few super teams. That is, while competitive balance may matter for local interest in a team, imbalance may help drive outside demand to see truly elite play.

[Page 81]

——–

Notes:

1. An earlier version of this article appeared in: 24 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal (Spring 2013), published by the New York State Bar Association, One Elk Street, Albany, NY 12207.

2. Dan Rascher is a sports and antitrust economist, a Full Professor at the University of San Francisco, and founding partner of OSKR and president of SportsEconomics. Andy Schwarz is an antitrust economist with a subspecialty in sports economics. He is a founding partner of OSKR and a co-founder of the Historical Basketball League.

3. 468 U.S. 85, 102 (1984).

4. Id. at 102.

5. O’Bannon v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 802 F.3d 1049 (9th Cir. 2015).

6. O’Bannon v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 7 F. Supp. 3d 955, 978-79 (N.D. Cal. 2014) (noting that testimony by plaintiffs’ expert witnesses cited several academic publications that showed the lack of a relationship between the pay restrictions and competitive balance), aff’d in part, vacated in part, 802 F.3d 1049 (9th Cir. 2015).

7. O’Bannon, 802 F.3d at 1072 ("We therefore accept the district court’s factual findings that the compensation rules do not promote competitive balance. . . .").

8. In re Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058 (N.D. Cal. 2019) (also known as Alston v. NCAA).

9. FBS stands for Football Bowl Subdivision, the set of approximately 130 schools that play football at the highest collegiate level. FBS was formerly known as Division 1A. At the time the Alston litigation was filed, there were 11 such conferences. In the interim, the Western Athletic Conference (WAC) stopped sponsoring football, so there are now 10 such conferences.

10. In re Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., No. 14-CV-02758-CW, 2018 WL 1524005, at *10, n.7 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 28, 2018).

11. See, e.g., Daniel A. Rascher, Joel Maxcy & Andrew D. Schwarz, The Unique Economic Aspects of Sports, at 8 (Jan. 5, 2019) (". . . despite the existence of so many team-sport league policies, such as restrictions on competitive markets for players’ services and revenue sharing between clubs, that are publicly justified by an appeal to the need for outcome uncertainty and competitive balance, empirical tests by sports economists have repeatedly found (a) little effect of outcome uncertainty on consumers demand for sports, and (b) little effect of most policy changes on competitive balance. In lay terms, the rules do not seem to help competitive balance, and competitive balance doesn’t seem to sell that many tickets anyway.").

12. Walter Neale, The Peculiar Economics of Professional Sports: A Contribution to the Theory of the Firm in Sporting Competition and Market Competition, 78 Q. J. OF ECON. 1, 1-14 (1964).

13. When Neale wrote his paper, the A’s were still located in Kansas City and were notoriously bad. During their thirteen years (1955-1967) in Kansas City, the A’s lost almost 60% of their games.

14. See Michael A. Flynn & Richard J. Gilbert, The Analysis of Professional Sports Leagues as Joint Ventures, 111 The Econ. J. F27, F44-45 (2001).

15. Finley & Co., Inc. v. Kuhn, 569 F.2d 527, 538 (7th Cir. 1978), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 876 (1978).

16. Coates, D., Humphreys, B. R., & Zhou, L., Outcome Uncertainty, Reference-Dependent Preferences and Live Game Attendance, Economic Inquiry, 52, 959-973 (2014). Humphreys, B. R., & Zhou, L., The Louis-Schmeling Paradox and the League Standing Effect Reconsidered, Journal of Sports Economics, 16, 835-852 (2015).

17. Within-game balance essentially means that the outcome of the game is typically decided near the end of the game. This has been shown to have an impact on television ratings during the game, as viewers stop watching a game that has essentially been decided. Game-to-game balance means teams have an equal chance of winning every game, so that last game’s winner is no more likely to win than last game’s loser. Season-to-season balance means every team has an equal chance to win each year, regardless of how they did the prior season.

18. Rodney Fort describes the various measures of competitive balance. He also notes that the NFL has had the most balance over the years and attributes at least some of that to salary caps. Rodney Fort, Competitive Balance in North American Professional Sports, Handbook of Sports Economic Research 190, 190-206 (John Fizel ed., 2006).

19. Rodney J. Paul & Andrew B. Weinbach, The Uncertainty of Outcome and Scoring Effects of Nielsen Ratings for Monday Night Football, 59 J. of Econ. & Bus. 199, 210 (2012).

20. Daniel A. Rascher, A Test of the Optimal Positive Production Network Externality in Major League Baseball, Sports Economics: Current Research, 37 (John Fizel, et al. eds., Praeger Press 1999).

21. Martin B. Schmidt & David J. Berri, The Impact of Labor Strikes on Consumer Demand: An Application to Professional Sports, 94 Am. Econ. Review, 344, n. 1 (2004).

22. Board of Regents, 468 U.S. at 102.

23. American Needle, Inc. v. National Football League, 130 U.S. 2201 (2010).

24. See discussions of O’Bannon and Alston and accompanying notes 5-11, supra.

25. Rascher Direct Testimony, ¶4, In re Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., No. 14-md-02541 CW (N.D. Cal.).

26. See Neale, supra note 10.

27. Exogenous means "from the outside" and refers to forces outside of the control of the parties to the transaction, in contrast to "endogenous" forces within their control. A college soccer team’s budget is set endogenously by the college, but a change in demand for soccer in the US, driven by the popularity of the FIFA video game, would result in an exogenous change in demand for that col lege’s soccer team’s ticket s.

28. For a discussion of single sport leagues, see Paul C. Weiler, et al., Sports and the Law: Text, Cases, and Problems, 743 (4th ed. 2011).

29. In 1903, the American and National Leagues which agreed on rules about player employment did not merge. The two leagues also had separate offices and presidents until 1999. Pooled sales of broadcasting rights only occurred in 1962, and interleague play only started in 1997.

30. https://www.foxbusiness.com/features/ufc-one-championship-tnt-deal-north-america

31. Gerald Scully, The Market Structure of Sports, 23 (University of Chicago Press 1995).

32. Michael E. Canes, The Social Benefits of Restrictions on Team Quality, in GOVERNMENT AND THE SPORTS BUSINESS 81, 95 (Roger G. Noll ed., 1974). In the same book, Roger Noll noted that average quality of play was likely higher when there are fewer teams, but also it was unknown how important that was to fans (as opposed to close competitions). Id. at 412.

33. Id. at 95.

34. Katie Baird, Dominance in College Football and the Role of Scholarship Restrictions, J. of Sport Mgmt,18, 233 (2004).

35. See www.HBLeague.com.

36. United States Football League, et al. v. Nat’l Football League, et al., 842 F.2d 1335, 1341 (2d Cir. 1988).

37. Or as was noted that much more economic research is needed to determine the degree and type of competition that exist across sports franchises (whether in the same sport or different sports). See Kenneth Lehn & Michael Sykuta, Antitrust and Franchise Relocation in Professional Sports: An Economic Analysis of the Raiders Case, 42 Antitrust Bull. 541, 563 (1997).

38. Economically, this concept is referred to as cross-price elasticity of demand.

39. For example, in USFL v. NFL (supra note 37), it was determined there was a relevant market consisting of major-league professional football in the United States. In Chicago Professional Sports Limited Partnership and WGN Continental Broadcasting Company, v. NBA (known as the Bulls case), 808 F.Supp. 646 (N.D. Ill.) the court decided the case in the context of a market in which production was measured as the number of basketball games on TV.

40. This is in contrast with key inputs, such as players or coaches where a given professional league is rarely a substitute for another as a potential employer for a highly skilled athlete. For the idea of each league/sanctioning body as a monopolist or single buyer in a labor market, see Brady v. Nat’l Football League, 640 F.3d 785 (8th Cir. 2011), O’Bannon v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 802 F.3d 1049 (9th Cir. 2015), In re Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058 (N.D. Cal. 2019), Le v. Zuffa, LLC, 216 F. Supp. 3d 1154 (D. Nev. 2016), and McNeil v. Nat’l Football League, 790 F. Supp. 871 (D. Minn. 1992). With respect to venues and other elements of professional sports marketing, it is often hard to see who is buying and who is selling. The discussion about who is a buyer and who is a seller is similar (but distinguishable) to the relatively new research on two-sided markets that was spawned by the credit card lawsuits. See, e.g., Jean-Charles Rochet & Jean Tirole, Cooperation Among Competitors: Some Economics of Payment Card Associations, 33 Rand J. of Econ., 549 (2002). Under this hypothesis, the NFL would be seen as a two-sided market that brings together fans and apparel makers, charging both of them (and adding some valuable intellectual property to up the ante). Similarly, the NFL is a two-sided market bringing together fans, sponsors, and facilities and charging each of them access to the other. However, the recent Supreme Court ruling has made it clear that while many entertainment markets, including sports, have elements of two-sided (or multi-sided) markets, they do not fit into the classic "platform" type of two-side market, where what the platform sells the connection. See Ohio v. American Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274 (2018).

Specifically, while NFL teams may provide sponsors with access to fans, they are not really selling sponsors to fans. Thus, just as the Court distinguished newspapers which sell access to customers and advertisers but do not sell advertisers to customers from credit cards which do provide direct (and reciprocal) matchmaking between merchants and customers, so too should most sports markets be distinguished as well. For college sports to be akin to a credit card, fans would need to be paying directly for athletes’ services, with schools simply providing matchmaking services for a commission. Even in a cynical view of under-the-table payments, this is not how schools generate revenue from college sports, unless one believes colleges get a cut of "bag money" alleged to be paid by boosters to athletes.

Hence, in Alston, the Court rejected the idea that because fans want to watch athletes and athletes want to be watched by fans, college sports is a two-sided market. The court pointed to American Express for the simple distinction, that is, to be a true two-sided platform, there must be a "simultaneous interaction or proportional consumption through a platform by different market participants of what essentially constitutes ‘only one product.’" The court thus concluded that "The multi-sided relevant market proposed by Dr. Elzinga is not analogous to the relevant market that the Supreme Court recognized as two-sided in American Express. In this litigation, the market participants and their interactions are nothing like what the Supreme Court observed in the context of credit-card transactions in American Express." In re Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n Athletic Grant-In-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., No. 14-MD-02541 CW, 2018 WL 4241981, at *4 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 3, 2018)

With that said, in entertainment markets, even if it’s clear the market is a standard one-sided one where supply moves downstream to the ultimate customer, the question of who is buying and who is selling (or if both parties are doing both) can be a difficult one to answer.

41. Daniel A. Rascher, Matthew T. Brown, Mark S. Nagel & Chad D. McEvoy, Where Did National Hockey League Fans Go During the 2004-2005 Lockout? An Analysis of Economic Competition Between Leagues, 5 Int’l J. Sport Mgmt. & Marketing, 183, 192 (2009). Using the natural experiment of the NHL lockout in 2004, the research analyzed what happened to NBA franchises and minor hockey league franchises in terms of attendance. The NBA saw an increase in attendance of approximately 3.2%, while the minor hockey leagues saw increases ranging from 0% to 6%. The analysis controlled for other factors and looked at the years prior to and post-lockout.

42. Roger G. Noll, Attendance and Price Setting, Government and the Sports Business, 115, 124,150 (Roger G. Noll ed., 1974). Noll defines this as a city with a metropolitan population of 3.5 million and 3 other professional sports teams.

43. Jason A. Winfree, Jill J. McCluskey, Ron C. Mittelhammer, & Rodney Fort, Location and Attendance in Major League Baseball, Applied Economics, 36, 2117-2124 (2004) (The study used a travel-cost model to analyze the attendance impacts on MLB of the closest substitute MLB team. The study also found that when a new team moves into the area of an existing team, there is an additional initial reduction in attendance for the incumbent team. The authors found that each mile closer an MLB team moved from the sample average translated to 1,544 fewer attendees for the year, or nearly $47,000 in ticket revenue losses. This is consistent with Rascher et al., who found that NFL teams lose about 2% of local revenues, all else equal, for each additional major professional sports team that is located in its metropolitan area. See Daniel Rascher, Matthew T. Brown, Chad E. McEvoy, & Mark S. Nagel, Financial Risk Management: The Role of a New Stadium in Minimizing the Variation in Franchise Revenues, J. of Sports Econ., 13, 431 (2012).

44. Some evidence of price competition across sports is found by Mills et al., yet more research needs to be done. Brian M. Mills, Jason A. Winfree, Mark S. Rosentraub & Ekaterina Sorokina, Fan Substitution Between North American Professional Sports Leagues, Applied Economics Letters, 22:7, 563-566.

45. See SportsEconomics, LLC, The Effects on SVSE and the City of San Jose from The Oakland Athletics Relocating to San Jose, 12 (Dec. 11, 2009) (consulting reporting prepared for Silicon Valley Sports and Entertainment (SVSE)).

46. While the 2004 work stoppage may be a cause of this decline, average attendance at NHL games during the season after the lockout was up by 2.5% compared with the year before the lockout. Moreover, the rest of the NHL experienced this increase in attendance while also raising prices by 2.5%. In contrast, the Capitals lowered ticket prices by 9% during the two years after the NHL lockout compared with the previous two years and still experienced a decline when the Nationals came to Washington. Id.

47. Stephen L. Shapiro, Tim DeSchriver & Daniel Rascher, Factors Affecting the Price of Luxury Suites in Major North American Sports Facilities, 26 J. of Sport Mgmt. 249, 249 (2012).

48. See SportsEconomics, LLC, The Effects on SVSE and the City of San Jose from The Oakland Athletics Relocating to SanJose, 12 (Dec. 11, 2009).

49. Id. Of course, as with all such natural experiments, this decline may be driven, at least in part, by other factors.

50. See Dennis W. Carlton, Alan S. Frankel, & Elisabeth M. Landes, The Control of Externalities in Sports Leagues: An Analysis of Restrictions in the National Hockey League, 112 J. of Political Econ. no. 1, S268 (2004); David Boyd & Boyd, Laura, The Home Field Advantage: Implications for the Pricing of Tickets to Professional Team Sporting Events, 22 J Econ. & Fin. 169; Ha Hoang & Daniel Rascher, The NBA, Exit Discrimination, and Career Earnings, 38 Indus. Rel., no. 1 (Jan. 1999); Daniel Rascher, A Test of the Optimal Positive Production Network Externality in Major League Baseball, Sports Econ.: Current Research (1999); Daniel Rascher & Heather Rascher, NBA Expansion and Relocation: A Viability Study of Various Cities, 18 J. Sport Mgmt. 274, no. 3 (July 2004); Depken, C. A., III, Fan Loyalty and Stadium Funding in Professional Baseball, 1 J. Sports Econ., no.2, 124-138 (May 2002) (using MLB data from 1991-2001); Brian M. Mills, Michael Mondello & Scott Tainsky, Competition in shared markets and Major League Baseball broadcast viewership, Applied Economics, 48:32, 3020-3032 (2016).

51. In some sports, such as international soccer and American college sports, regional leagues have been successful despite the tendency for fans to want a single league of best-against-best. European soccer leagues have managed this through the use of the Champions League, while college sports has relied on its post-season (i.e., CFP for football and "March Madness" for basketball, as well as inter-conference (inter-league) play).

52. In some cases, these agreements have also included individual player maximum salaries.

53. With the definition of revenue adjusted based on the collective bargaining process.

54. Kevin G. Quinn, Getting to the 2011-2020 National Football League Collective Bargaining Agreement, 7 Int’l J. of Sport Fin. 141, 145 (2012).

55. Marvin Powell, et al. v. Nat’l Football League, et al., 930 F.2d 1293 (8th Cir. 1989).

56. Id.; see also Quinn, supra note 54.

57. McNeil et al. v. Nat’l Football League, 790 F. Supp. 871 (D. Minn. 1992).

58. White v. Nat’l Football League, 585 F.3d 1129, 1134 (8th Cir. 2009).

59. See Quinn, supra note 54, at 146.

60. Collective Bargaining Agreement Between the NFL Management Council and The NFL Players Association, 86-142 (1993), available at https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1572&context=blscontracts.

61. See id.; see also Scott McPhee, First Down, Goal to Go: Enforcing the NFL’s Salary Cap Using the Implied Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing, 17 Loy. L.A. ENT. L. J. 449, 457-58 (1997).

62. DGR was an NFL term of art that includes most NFL national revenue but excluded certain local revenues such as luxury suite revenues.

63. John Vrooman, Theory of the Perfect Game: Competitive Balance in Monopoly Sports Leagues, 34 Rev. of Indus. Org., 5, 11 (2009), available at https://my.vanderbilt.edu/vrooman/files/2016/06/Vrooman-perfectgame.pdf.

64. Gary Myers, NFL Collective Bargaining Agreement Includes No Opt- Out, New Revenue Split, Salary Cap, Rookie Deals, N.Y. Daily News (July 26, 2011), available at http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/football/nfl-collective-bargaining-agreement-includes-no-opt-out-new-revenue-split-salary-cap-rookie-deals-article-1.162495.

65. Dan Graziano, 2021 NFL CBA Negotiations: The Nine Biggest Looming Issues, ESPN (July 3, 2019), available at https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/27103713/2021-nfl-cba-negotiations-nine-biggest-looming-issues.

66. Daniel Rascher, A Model of a Professional Sports League, Advances in the Econ. of Sport, 2 (1997).

67. Adam Schefter, Chris Mortensen, John Clayton & Andrew Brandt, NFLPA Still Discussing Proposed Deal, ESPN (July 23, 2011), available at http://espn.go/nfl/story/_/id/6793054/nfl-lockout-nflpa-work-weekend-sources-say.

68. Brady v. Nat’l Football League, 644 F.3d 661 (8th Cir. 2011).