Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law

Competition: Fall 2018, Vol 28, No. 1

Content

- Above Frand Licensing Offers Do Not Support a California Ucl Action In Tcl V Ericsson

- Antitrust Is Already Equipped To Handle "Big Data" Issues

- Antitrust, Privacy, and Digital Platforms' Use of Big Data: a Brief Overview

- Applying Illinois Brick To E-Commerce: Who Is the Direct Purchaser From An App Store?

- Chair's Column

- D-Link Systems: Possible Signs For the Future of Ftc Data Security Enforcement

- Editor's Note

- Masthead

- "No-poach" Agreements As Sherman Act § 1 Violations: How We Got Here and Where We're Going

- Smart Contracts and Blockchains: Steroid For Collusion?

- The Difficulties of Showing Pass Through In Indirect Purchaser Component Cases

- The Hold-up Tug-of-war—Paradigm Shifts In the Application of Antitrust To Industry Standards

- Antitrust Treatment of the Introduction of New Drug Products: the Tension Between Hatch-waxman's Dual Goals of Cheaper Drugs and Better Drugs

ANTITRUST TREATMENT OF THE INTRODUCTION OF NEW DRUG PRODUCTS: THE TENSION BETWEEN HATCH-WAXMAN’S DUAL GOALS OF CHEAPER DRUGS AND BETTER DRUGS

by Rosanna K. McCalips1

Much has been said about the cost savings generated by generic drugs made more widely available by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act (commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act or the Hatch-Waxman Amendments). The Association for Accessible Medicines (formerly known as the Generic Pharmaceutical Association) reported that generic drug use saved the U.S. healthcare system $253 billion in 2016.2 But consumer welfare also has risen tremendously from the innovation the Hatch-Waxman Act spurred. Indeed, studies show that the use of new outpatient prescription drugs lengthened life expectancy in the United States by more than a year from 1991 to 2004.3 In addition to extending life, innovations in prescription drugs have also enhanced the quality of life for many Americans. New and improved drugs have enabled the elderly to perform daily functions such as eating, dressing, and bathing with greater ease.4 And new drugs have decreased the percentage of Americans receiving Social Security Disability.5

These benefits are not due entirely, or even mostly, to new "blockbuster" drugs, but rather result in large part from incremental improvements of existing therapies. One study in the peer-reviewed journal PharmacoEconomics found that "innovation that takes the form of improved formulations, delivery methods and dosing protocols may also generate substantial benefits associated with improved patient compliance, greater efficacy as a result of improved pharmacokinetics, reduced adverse effects or the ability to effectively treat new patient populations."6

[Page 70]

Congress, through the Hatch-Waxman Act, intended both to "incentivize drug manufacturers to invest in new research and development" as well as to "encourage generic entry into the marketplace."7 The potential tension between these two goals is apparent in antitrust cases alleging a brand-name pharmaceutical company made "trivial" changes to its product to thwart generic competition—a practice called "product hopping." This article examines how the two Circuit Court opinions issued to date in product-hopping cases have reconciled the dual goals of the Hatch-Waxman Act—both of which enhance consumer welfare but in different ways—in assessing product-hopping claims.

I. HATCH-WAXMAN ACT BACKGROUND

To put product-hopping cases in context, one must understand how drug approval in the United States works. Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA),8 before a drug may be lawfully sold in the United States, the sponsor of the drug must demonstrate to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that the drug is safe and effective for the intended use and that the benefits of the drug exceed its risks.9 The Hatch-Waxman Act is a federal law that became effective in 1984 and amended the FDCA.10 The Hatch-Waxman Act has been described as "a compromise between two competing sets of interests: (1) those of innovative drug manufacturers, who had seen their effective patent terms shortened by the testing and regulatory processes; and (2) those of generic drug manufacturers, whose entry into the market upon expiration of the innovator’s patents had been delayed by similar regulatory requirements."11 The dual purposes of the Hatch-Waxman Act were "to make available more low cost generic drugs by establishing a generic drug approval procedure for pioneer drugs first approved after 1962" and "to create a new incentive for increased expenditures for research and development of certain products which are subject to premarket government approval."12

The goal of expediting generic entry is achieved by providing an abbreviated pathway for approval of generic drugs. Rather than having to perform the "long, comprehensive, and costly testing process" necessary in the first instance to prove a drug is safe and effective for its intended use, generic drug companies can submit Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) that "piggy-back" on the safety and efficacy studies contained in the approved New Drug Application (NDA) submitted by the innovator company.13The generic company must demonstrate that its generic product contains the same active ingredient as the innovator product and is bioequivalent to the innovator product, meaning "the rate and extent of absorption" of the active ingredient in the body is the same as that of the brand drug.14 In addition to providing for a shortened pathway to approval, the Hatch-Waxman Act further incentivizes generic entry by making available a period of 180 days of exclusivity (during which no other generic will be approved) to the first generic company to submit an ANDA that challenges the validity or infringement of the brand company’s patents on the drug.15 This 180-day exclusivity can be extremely lucrative for generic companies.16

[Page 71]

State laws also provide an additional benefit to generic drug companies in the form of automatic substitution of therapeutically equivalent generic drugs in place of prescribed brand-name drugs. Specifically, if the generic drug is therapeutically equivalent to the innovator product—meaning it has the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, and route of administration as the brand drug—the FDA will designate the generic drug as "AB-rated" in an FDA publication commonly known as the "Orange Book."17 All 50 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that permit or require pharmacists to substitute generic drugs that are listed in the Orange Book as AB-rated to the brand (or meet other criteria for therapeutic equivalency as specified in the statute) when filling prescriptions written for the brand-name drug unless the doctor writes on the prescription "dispense as written" (known as "automatic substitution").18 The AB-rating "carries a considerable corollary benefit for generics under state law"19 because it allows the drug to be automatically substituted when a prescription is written for a brand-name drug, thereby providing generic drug companies access to an established source of demand without any marketing efforts. Importantly for product-hopping cases, generic copies of the old version of a drug will not be AB-rated to the new version (due, for example, to differences in strength or dosage form). Thus, a pharmacist presented with a prescription for the new drug cannot automatically substitute a generic version of the old drug. Importantly, however, ordinarily a pharmacist is permitted (and in some states is required) to automatically substitute an available generic version of the old drug if the prescription is written for the brand-name version of the old drug even if the brand-name version of the old drug is no longer available.

[Page 72]

The Hatch-Waxman Act achieves its second goal of incentivizing the development of new drugs by extending the length of patent protection to compensate for the length of time it took to obtain FDA approval for the drug (known as "patent-term restoration").20 In addition, the Hatch-Waxman Act provides periods of regulatory exclusivity (meaning the FDA cannot approve a generic drug) of five years for a drug whose active ingredient is a new chemical entity not previously approved for use in the United States.21 And, of particular relevance to the product-hopping issue, Congress expressly amended the proposed legislation to provide three years of regulatory exclusivity for existing drugs containing "nonnew chemical entities . . . which have undergone new clinical studies essential to FDA approval."22 This exclusivity is available for newly filed NDAs as well as supplements to previously approved NDAs.23 The Hatch-Waxman Act also provides an additional six months of patent exclusivity in exchange for performance of pediatric studies requested by the FDA.24 In addition, Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 to provide a greater incentive to develop so-called "Orphan Drugs" that treat (a) rare conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States each year; or (b) conditions affecting more than 200,000 people in the United States each year but for which there is no reasonable expectation that the cost of developing the drug will be recovered from commercial sales.25 The Orphan Drug Act provides seven years of regulatory exclusivity during which generic versions will not be approved.26

II. PRODUCT-HOPPING: THE INTERSECTION OF FDA LAWS AND REGULATIONS AND THE ANTITRUST LAWS

Antitrust cases based on the introduction of a new drug product and (typically) the cessation of sales of the old version of the drug (called "product-hopping cases") pit the two goals of the Hatch-Waxman Act against each other. They also require courts to balance various goals of the antitrust laws because the antitrust laws recognize that consumer welfare is enhanced not only through cheaper prices but also through better quality products:

Today it seems clear that the general goal of the antitrust laws is to promote "competition" as the economist understands that term. Thus we say that the principal objective of antitrust policy is to maximize consumer welfare by encouraging firms to behave competitively while yet permitting them to take advantage of every available economy that comes from internal or jointly created production efficiencies, or from innovation producing new processes or new or improved products.27

[Page 73]

The Supreme Court has recognized that exclusivities like those provided by the Hatch-Waxman Act incentivize innovation: "The opportunity to charge monopoly prices—at least for a short period—is what attracts ‘business acumen’ in the first place; it induces risk taking that produces innovation and economic growth."28 Moreover, "[a]ntitrust scholars have long recognized the undesirability of having courts oversee product design, and any dampening of technological innovation would be at cross-purposes with antitrust law."29 But, "[b]ecause, speaking generally, innovation inflicts a natural and lawful harm on competitors, a court faces a difficult task when trying to distinguish harm that results from anticompetitive conduct from harm that results from innovative competition."30

In a traditional product-hopping antitrust case, introduction of a new product and the related removal of an old product may constitute exclusionary conduct under Section 2 of the Sherman Act if it reduces consumer choice. But proving such conduct is only the first step in establishing antitrust liability. Once this conduct is proven, the burden then shifts to the defendant to prove a non-pretextual, pro-competitive justification for the conduct, under the Microsoft burden-shifting, rule-of-reason test that some courts have applied in the Section 2 context.31 Ultimately, the plaintiff must show that the anticompetitive harm outweighs the non-pretextual, procompetitive benefits of the product innovation.32 Moreover, a plaintiff also must prove the other elements of an antitrust claim, including market power in a relevant market, antitrust injury, causation, and damages. But even if antitrust liability is not ultimately imposed, subjecting new drugs to expensive antitrust litigation risks deterring innovation and further driving up the cost of drugs. Thus, courts must carefully consider product-hopping cases at the motion-to-dismiss stage and only allow to proceed those cases that plausibly allege exclusionary conduct as opposed to consumer-welfare-enhancing conduct that harms competitors merely because the new product competes with generic versions of the old product.

[Page 74]

Two Circuit Court have recently struggled with these concepts when faced with product-hopping cases, as discussed below.

III. SUMMARY OF PRODUCT-HOPPING APPELLATE DECISIONS

There are only two Circuit Court decisions addressing product-hopping claims. The first was New York ex rel. Schneiderman v. Actavis PLC (Namenda), 787 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 2015), and the second was Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Public Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F.3d 421 (3d Cir. 2016). The Second Circuit in Namenda held that the defendant’s conduct in introducing a new version of a drug and discontinuing sales of the old version was anticompetitive because it coerced doctors and patients into using the new product. By contrast, the Third Circuit in Doryx held the product introductions and discontinuations alleged in that case did not exclude generic competition and thus did not violate the antitrust laws.

[Page 75]

A. New York Ex Rel. Schneiderman v. Actavis PLC (Namenda), 787 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 2015)

In Namenda, the brand manufacturer, facing the expiration of its patent for Namenda IR, an immediate-release product for treating mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, introduced Namenda XR, an extended-release version of the drug. Whereas Namenda IR had to be taken twice daily, Namenda XR was a once daily treatment. The brand company sold Namenda IR and Namenda XR side by side at first but later announced plans to effectively withdraw Namenda IR from the market prior to generic entry by limiting distribution of Namenda IR to a single mail-order pharmacy that would only distribute it if the patient’s doctor certified that it is "medically necessary."33 The brand company also asked Medicare & Medicaid Services to remove Namenda IR from its formulary. 34

The Second Circuit affirmed the Southern District of New York’s grant of a preliminary injunction requiring the brand company to "continue to make Namenda IR (immediate-release) tablets available on the same terms and conditions applicable since July 21, 2013," to "inform healthcare providers, pharmacists, patients, caregivers, and health plans of this injunction . . . and the continued availability of Namenda IR," and to "not impose a ‘medical necessity’ requirement . . . for Namenda IR" until "thirty days after July 11, 2015 (the date when generic memantine will first be available)."35 Importantly, the Second Circuit did not take issue with the introduction of Namenda XR itself:

As long as Defendants sought to persuade patients and their doctors to switch from Namenda IR to Namenda XR while both were on the market (the soft switch) and with generic IR drugs on the horizon, patients and doctors could evaluate the products and their generics on the merits in furtherance of competitive objectives.36

Rather, it was the "hard switch" that the court found objectionable under the antitrust laws:

Here, Defendants’ hard switch—the combination of introducing Namenda XR into the market and effectively withdrawing Namenda IR—forced Alzheimer’s patients who depend on memantine therapy to switch to XR (to which generic IR is not therapeutically equivalent) and would likely impede generic competition by precluding generic substitution through state drug substitution laws.37

[Page 76]

The court viewed this conduct as coercive because it was taken "with the knowledge that transaction costs would make the reverse commute by patients from XR to generic IR highly unlikely."38 Specifically, "the nature of Alzheimer’s disease makes moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s patients especially vulnerable to changes in routine, and makes doctors and caregivers very reluctant to change a patient’s medication if the current treatment is effective."39 In this context, the court concluded that defendant’s introduction of a new product and removal of an old product before generic entry for the old product could occur interfered with the "free choice of consumers" and, as such, was actionable under the antitrust laws.40

B. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Public Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F.3d 421 (3d Cir. 2016)

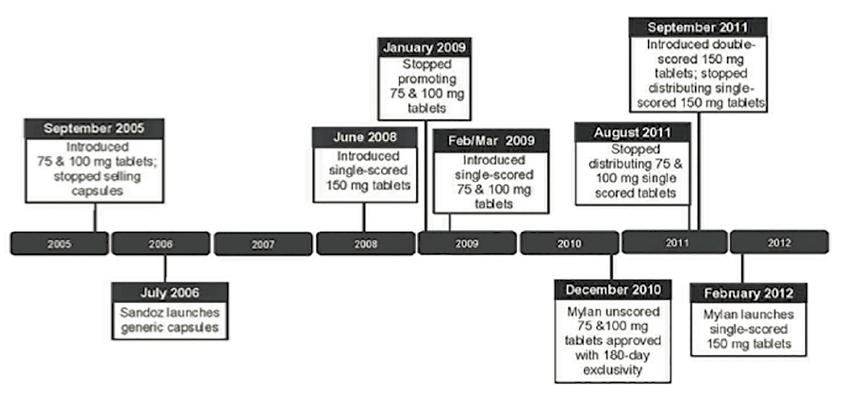

In Doryx, the Third Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment for the defendants on a product-hopping claim.41 Mylan, a generic competitor, challenged four product changes to the acne medication Doryx (delayed-release doxycycline hyclate) including a change from capsule form to tablet form and later changes to the strength and scoring of the tablets.42

The court held that the product changes were not exclusionary because (a) a generic company other than the plaintiff was able to launch a generic version of the old capsule product; (b) the plaintiff Mylan was able to launch generic versions of the single-scored 75mg and 100mg tablets; and (c) Mylan obtained 180-days of regulatory exclusivity for being the first generic to successfully challenge the patents covering Doryx, enabling Mylan to earn $146.9 million on sales of its generic versions of Doryx 75mg and 100mg tablets (at times even charging a higher price for its generic than the brand price).43

As the following timeline shows, generic companies (shown below the timeline) were able to launch competing versions of Doryx capsules and the various tablet versions of Doryx. The brand manufacturer’s conduct (shown above the timeline) did not interfere with generic entry and consumer choice but rather introduced new products and allowed the market the opportunity to choose.

[Page 77]

Doryx Timeline

Image description added by Fastcase.

Although the court’s determination that the defendant did not engage in exclusionary conduct was a sufficient basis for dismissal in Doryx, the court went on to find that the defendant also had presented unrebutted evidence of procompetitive justifications for the product changes including (a) esophageal problems related to the capsules (which resulted in a product liability lawsuit in the United States and the capsules being banned in two European countries); (b) shelf-life problems that led to a massive recall of the capsules; and (c) allowing "consumers to more effectively self-dose at patient-specific levels" by adding scores to the tablets (which make it easier to evenly break the pills).44 Thus, it appears the defendant in Doryx also would have prevailed at the subsequent stages of the Microsoft burden-shifting rule-of-reason test.

IV. TO ACHIEVE THE GOALS OF THE HATCH-WAXMAN ACT AND THE ANTITRUST LAWS, COURTS MUST NOT DETER INNOVATION

To be sure, generic competitors may be harmed by the introduction of an improved version of a drug because the new version will compete with the generic version. But, it must always be remembered that the antitrust laws "were enacted for ‘the protection of competition, not competitors.‘"45 To that end, courts considering product-hopping cases must be careful to ensure that the antitrust laws are applied "not against conduct which is competitive, even severely so, but against conduct which unfairly tends to destroy competition itself."46 If a small change to a drug is of sufficient value to the doctors and patients who actually use the drug on a daily basis, consumer welfare is enhanced by that innovation.

Cheaper products are, of course, one of the goals and benefits of competition, but "product superiority is one of the objectives of competition" as well.47 Although "[i]nnovation necessarily disadvantages rivals who do not keep up,"48 it is axiomatic that "[t]he attempt to develop superior products . . . is an essential element of lawful competition."49 Congress did not amend this fundamental principle of antitrust law when enacting the Hatch-Waxman Act. Indeed, Congress enacted the Hatch-Waxman Act with the dual goals of speeding the availability of lower-cost generic versions of drugs and incentivizing innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. While generic drugs have their role in making drugs cheaper, it must be remembered that companies that launch generic versions of existing drugs are not introducing innovative products. Rather, by statute, a generic drug must have the same active ingredient, route of administration, dosage form, and strength as the brand-name drug.50 It is because generics bear no expense or risk in developing a new drug but instead copy already successful (and profitable) brand-name drugs that they can sell their generic versions at a steep discount off the brand price. Thus, to preserve the consumer welfare gains that come from innovation, which was undeniably one of the goals of the Hatch-Waxman Act, courts must be careful not to discourage brand-name drug companies from introducing new drug products.51 After all, Congress, in what is "quintessentially a matter for legislative judgment," struck "a balance between incentives, on the one hand, for innovation, and on the other, for quickly getting lower-cost generic drugs to market."52 As the Third Circuit in Doryx noted, "Congress could have chosen to bar or significantly restrict name-brand drug manufacturers from making changes that would delay generic entry, but it did not do so."53

[Page 78]

Namenda rejected the argument that subjecting new-product introduction to antitrust scrutiny will deter innovation because defendants "presented no evidence to support their argument that antitrust scrutiny of the pharmaceutical industry will meaningfully deter innovation."54 Importantly, however, Namenda considered the deterrent effect on innovation only after holding that the conduct at issue was exclusionary (at the third step of the Microsoft test that weighs the procompetitive benefits of the exclusionary conduct against its anticompetitive effects). In cases in which there is no exclusionary conduct

[Page 79]

because consumers are not coerced, the risk of deterring innovation by imposing the prospect of expensive and burdensome antitrust scrutiny merely because a new product is introduced and a prior version of the product is retired remains a valid concern. Moreover, the Namenda court credited an argument in an amicus brief submitted by the American Antitrust Institute (AAI) that "immunizing product hopping from antitrust scrutiny may deter significant innovation by encouraging manufacturers to focus on switching the market to trivial or minor product reformulations rather than investing in the research and development necessary to develop riskier, but medically significant innovations."55 This argument, however rests on the premise that only entirely new drugs constitute "medically significant" innovations and ignores the significant consumer benefit that comes from incremental improvements to existing drug therapies.56 The argument also relies on an outdated view that the pharmaceutical market has a "defect" due to a "price disconnect" between those who choose but do not pay for the drug (i.e., doctors) and those who pay for the drug but do not choose it (i.e., patients and their insurers).57 This view of the pharmaceutical market ignores the fact that patients and doctors are now highly aware of the existence of generic drugs and the cost savings they generate.58 Indeed, more recent surveys show that many patients routinely ask their doctors for generic drugs.59 Moreover, the AAI would have courts substitute their judgment for that of doctors and patients, turning courts into "tribunals over innovation sufficiency,"60 a task for which they are ill suited.61

[Page 80]

V. CONCLUSION

Because "the error costs of punishing technological change are rather high"62 and "any dampening of technological innovation would be at cross-purposes with antitrust law,"63 courts should tread carefully before imposing their value judgments on doctors, patients, and payers in the form of antitrust scrutiny of new product introductions. As long as consumers are generally free to choose between the old product and the new product, courts should leave to the market the determination of whether a product change is "sufficiently innovative." If instead of profiting from the lawful monopoly prices attendant to new drug development, drug companies are subjected to expensive and protracted antitrust litigation, the incentives to innovate provided by Congress through the Hatch-Waxman Act are lessened and there is a risk of deterring valuable innovation that extends and improves the quality of life for many Americans.

[Page 81]

——–

Notes:

1. Rosanna K. McCalips is an antitrust litigator at Jones Day in Washington, D.C. with more than ten years of experience defending drug companies against monopolization claims based on alleged product hopping and other conduct. The views and opinions set forth herein are the personal views or opinions of the author; they do not necessarily reflect views or opinions of the law firm with which she is associated.

2. Association for Accessible Medicines, Generic Drug Access & Savings in the U.S. (2017) at 20, available at https://accessiblemeds.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/2017-AAM-Access-Savings-Report-2017-web2.pdf (last accessed 7/13/2018).

3. Frank R. Lichtenberg, The Impact of Biomedical Innovation on Longevity and Health, 5 Nordic J. Health Econ. 45, 51 (2017) (finding use of newer outpatient prescription drugs increased life expectancy by 0.96 to 1.26 years between 1991 and 2004).

4. Id. at 54; see also Frank R. Lichtenberg, The Effect of Pharmaceutical Innovation on the Functional Limitations of Elderly Americans: Evidence from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 17750, 2012) at 14 (finding the ability of nursing home residents to perform activities of daily living such as eating, bathing, and dressing is positively related to the number of newer, i.e., post1990, medications they consume).

5. Frank R. Lichtenberg, The Effect of Pharmaceutical Innovation on the Functional Limitations of Elderly Americans: Evidence from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 17750, 2012) at 8; see also Frank Lichtenberg, Has Pharmaceutical Innovation Reduced Social Security Disability Growth, 18(2) Int’l J. Econ. Bus., 293-316 (2011) (estimating that in the absence of newer drugs, social security disability rate would have been 30% larger between 1995 and 2004).

6. Ernst R. Berndt, Iain M. Cockburn & Karen A. Grepin, The Impact of Incremental Innovation in Biopharmaceuticals: Drug Utilisation in Original and Supplemental Indications, 24 PharmacoEconomics 69, 71 (2006).

7. In re Modafinil Antitrust Litig., 837 F.3d 238, 242-43 (3d Cir. 2016).

8. 21 U.S.C. § 301 et seq. (1938).

9. See Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. § 355(d) (2017); Applications for FDA Approval to Market a New Drug, 21 C.F.R. §§ 314.50(d)(5)(viii) & 314.105(c) (2018).

10. Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, P.L. 98-417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984) (codified at 21 U.S.C. §§ 301, 355, 360cc; 35 U.S.C. § 156) (more commonly referred to as the Hatch-Waxman Act or the Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. § 301 et seq. (1938)).

11. Warner-Lambert Co. v. Apotex Corp., 316 F.3d 1348, 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

12. H.R. Rep. No. 98-857(1), at 14-15 (1984), reprinted in 1984 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2647, 2647-48.

13. F.T.C. v. Actavis, Inc., 570 U.S. 136, 142 (2013).

14. 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(8)(B)(i) (2017).

15. 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(5)(B)(iv) (2017).

16. See Picone v. Shire PLC, No. 16-CV-12396-ADB, 2017 WL 4873506, at *9 (D. Mass. Oct. 20, 2017) ("In short, it is well recognized that a generic monopoly during the 180-day exclusivity period is highly lucrative."); Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co. v. U.S. Food & Drug Admin., 587 F. Supp. 2d 1, 4 (D.D.C. 2008) ("The 180-day exclusivity period is a highly-coveted and lucrative benefit, as evidenced by the recurrence of litigation regarding the entitlement to it.").

17. The Orange Book is formally entitled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations.

18. See New York ex rel. Schneiderman v. Actavis PLC (Namenda), 787 F.3d 638, 644-45 (2d Cir. 2015) (citing Jesse C. Vivian, Generic-Substitution Laws, U.S. Pharmacist (June 19, 2008), available at http://www.uspharmacist.com/content/s/44/c/9787).

19. Mylan Pharms. Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Pub. Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F.3d 421, 428 (3d Cir. 2016).

20. 35 U.S.C. § 156 (2015). The length of the patent term remaining after patent-term restoration may not exceed fourteen years from the date of drug approval. 35 U.S.C. § 156(c)(3). Also, for patents obtained after enactment of the Hatch-Waxman Act, the period of extension cannot exceed five years. 35 U.S.C. § 156(g)(6)(A).

21. 21 U.S.C. §§ 355(c)(3)(E)(ii), (j)(5)(F)(ii).

22. 130 Cong. Rec. 24,425 (Sept. 6, 1984).

23. 21 U.S.C. §§ 355(c)(3)(E)(iii)-(iv), (j)(5)(F)(iii)-(iv).

24. 21 U.S.C. § 355a (2017).

25. P.L. 97-414, 96 Stat. 2049 (1983) (codified at 21 U.S.C. §§ 301, 360aa-360ee).

26. 21 U.S.C. § 360cc(a); 21 C.F.R. § 316.20(b)(8).

27. IIIB Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application ¶ 100a (CCH Incorporated 4th ed. Cum. Supp. 2018) (emphasis added); see also United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division Mission Statement, available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/mission (last accessed 7/13/2018) ("Competition in a free market benefits American consumers through lower prices, better quality and greater choice. Competition provides businesses the opportunity to compete on price and quality, in an open market and on a level playing field, unhampered by anticompetitive restraints.").

28. Verizon Commc’ns Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398, 407 (2004).

29. United States v. Microsoft Corp., 147 F.3d 935, 948 (D.C. Cir. 1998).

30. In re TriCor Antitrust Litig., 432 F. Supp. 2d 408, 421 (D. Del. 2006).

31. The Microsoft burden-shifting test is as follows:

First, to be condemned as exclusionary, a monopolist’s act must have an ”anticompetitive effect.” That is, it must harm the competitive process and thereby harm consumers. In contrast, harm to one or more competitors will not suffice. . . .

Second, the plaintiff, on whom the burden of proof of course rests . . . must demonstrate that the monopolist’s conduct indeed has the requisite anticompetitive effect.

Third, if a plaintiff successfully establishes a prima facie case under § 2 by demonstrating anticompetitive effect, then the monopolist may proffer a ”procompetitive justification” for its conduct. . . . If the monopolist asserts a procompetitive justification—a nonpretextual claim that its conduct is indeed a form of competition on the merits because it involves, for example, greater efficiency or enhanced consumer appeal—then the burden shifts back to the plaintiff to rebut that claim. . . .

Fourth, if the monopolist’s procompetitive justification stands unrebutted, then the plaintiff must demonstrate that the anticompetitive harm of the conduct outweighs the procompetitive benefit.

253 F.3d 34, 58-59. Importing the Section 1 rule-of-reason balancing test to the Section 2 context is problematic. After all, unilateral conduct is afforded greater latitude under our antitrust laws. See Copperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp., 467 U.S. 752, 767-68 (1984). Moreover, a balancing test risks subjecting to antitrust scrutiny a new product innovation that improves consumer welfare merely because that benefit is "outweighed" by the effect on generic competitors. Nonetheless, many courts have applied the Microsoft test to assess product-hopping claims. See, e.g., Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Pub. Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F.3d 421, 438 (3d Cir. 2016) ("In addressing allegations of anticompetitive conduct based on Defendants’ product hops, the District Court properly applied the ‘rule or reason’ burden-shifting framework set forth by the D.C. Circuit in United States v. Microsoft Corp.").

32. As of the time this article was drafted, no product-hopping claims had prevailed on the merits at trial or on summary judgment. Thus, it remains to be seen what evidence would be sufficient to prove that the anticompetitive effect of a product change outweighs the procompetitive benefits. But in light of econometric research showing the tremendous increase to consumer welfare from drug innovation, even from incremental innovation such as formulation changes, it would appear to be a heavy burden.

33. New York ex rel. Schneiderman v. Actavis PLC (Namenda), 787 F.3d 638, 648 (2d Cir. 2015).

34. Id.

35. Id. at 650.

36. Id. at 654.

37. Id.

38. Id. at 655.

39. Id. at 656. The district court found that Defendants engaged in the hard switch because they predicted "that only 30% of memantine-therapy patients would voluntarily switch to Namenda XR prior to generic entry" whereas the "hard switch was expected to transition 80 to 100% of Namenda IR patients to XR prior to generic entry." Id. at 654.

40. Id. at 654-55 (citing Berkey Photo, Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 603 F.2d 263, 287 (2d Cir. 1979)).

41. Mylan Pharms. Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Pub. Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F.3d 421, 441 (3d Cir. 2016).

42. Specifically, the challenged changes were: (1) from 75mg and 100mg capsules to 75mg and 100mg tablets; (2) introduction of a single-scored 150mg tablet; (3) adding a single score to the 75mg and 100mg tablets; and (4) changing from a single score to a dual score on the 150mg tablet.

43. 838 F.3d at 438-39.

44. Id. at 439.

45. Brunswick Corp. v. Pueblo Bowl-O-Mat, Inc., 429 U.S. 477, 488 (1977) (quoting Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 320 (1962)) (emphasis in original).

46. Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan, 506 U.S. 447, 458 (1993).

47. IIIB Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application ¶ 781a (CCH Incorporated 4th ed. Cum. Supp. 2018).

48. I Herbert Hovenkamp et al., IP and Antitrust: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles Applied to Intellectual Property Law, § 12.02 (CCH Incorporated 3rd ed. 2017 Supp.); see also In re Suboxone, 64 F. Supp. 3d 665, 679 (E.D. Pa. 2014) ("New and improved products are one of the benefits brought about by healthy competition.").

49. Berkey Photo, Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 603 F.2d 263, 286 (2d Cir. 1979).

50. See 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(2)(A).

51. Moreover, subjecting the introduction of a new product that may improve consumer welfare to potential antitrust liability not only risks deterring procompetitive innovation but also turns the courts into "tribunals over innovation sufficiency." Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Pub. Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F. 3d 421, 440 (3d Cir. 2016). It is simply "unadministrable" for a court "to weigh the benefits of an improved product design against the resulting injuries to competitors" because "[t]here are no criteria that courts can use to calculate the ‘right’ amount of innovation, which would maximize social gains and minimize competitive injury." Allied Orthopedic Appliances, Inc. v. Tyco Health Care Grp. LP, 591 F.3d 991, 1000 (9th Cir. 2010). That determination is best left to the market. See IIIB Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application ¶ 781c (CCH Incorporated 4th ed. Cum. Supp. 2018) ("We doubt that the court has any choice but to accept consumer sovereignty, especially in the absence of any criteria or calculus for deciding otherwise.").

52. Teva Pharm. Indus. Ltd. v. Crawford, 410 F.3d 51, 54 (D.C. Cir. 2005).

53. Doryx, 838 F.3d at 440 n.88.

54. 787 F.3d at 659.

55. Id.

56. See supra at 1.

57. Brief of the American Antitrust Institute as Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellees at 3, New York ex rel. Schneiderman v. Actavis PLC (Namenda), 787 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 2015) (No. 14-4624). The AAI amicus brief relies on studies from the 1970’s and 80’s regarding the price insensitivity of doctors. Id. at 7. But a lot has changed in the intervening decades in terms of the amount of information available to doctors and consumers about prescription drugs and their costs (e.g., through the internet). More recent studies have shown that doctors do sense their patients’ price sensitivities and adjust their prescribing practices accordingly. See, e.g., Mariana Carrera, Dana P. Goldman, Geoffrey Joyce & Neeraj Sood, Do Physicians Respond to the Costs and Cost-Sensitivity of Their Patients? 10 Am. Econ. J.: Econ. Pol. vol. 1, 113-52 (2018) (finding doctors can perceive the price sensitivities of their patients and adjust their initial prescriptions in response to large and universal price changes such as that associated with the expiration of patents). Thus, the market may not be as "flawed" as some once thought and the choice regarding which products are "real innovations" should not be usurped by the courts but instead given back to doctors and patients who are in the best position to assess the value of a drug product change.

58. See generally, William H. Shrank et al., Physician Perceptions About Generic Drugs, 45 Annals Pharmacotherapy 31, 34 (Jan. 2011) (survey of more than 500 physicians reports they become aware of generic market entry through pharmaceutical representatives (75%), medical journals (42%), colleagues (40%), and pharmaceutical mailings or literature (38%)).

59. See, e.g., William H. Shrank et al., Patients’ Perceptions of Generic Medications, 28 Health Aff. (Millwood) 546-56 at 549-51 (2009) (finding 33.2 % of patients surveyed ask their doctors to substitute generics for brand-name medications most or all of the time and 66.5% of patients surveyed reported feeling comfortable asking their doctors to substitute a generic for a branded medication).

60. Mylan Pharms. Inc. v. Warner Chilcott Pub. Ltd. (Doryx), 838 F.3d 421, 440 (3d Cir. 2016).

61. See generally IIIB Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application ¶ 775c (3d ed. 2018) ("[C]ourts are poorly equipped to evaluate the motives, significance, usefulness, or competitive or other effects of innovation.").

62. I Herbert Hovenkamp et al., IP and Antitrust: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles Applied to Intellectual Property Law § 12.1 (3rd ed. CCH Incorporated 2016).

63. United States v. Microsoft Corp., 147 F.3d 935, 948 (D.C. Cir. 1998).