Antitrust and Consumer Protection

Competition: Spring 2015, Vol. 24, No. 1

Content

- California Antitrust and Unfair Competition Law and Federal and State Procedural Law Developments

- California Antitrust and Consumer Protection Section Law and Federal and State Procedural Law Developments

- Chair's Column

- Editor's Note

- How Viable Is the Prospect of Enforcement of Privacy Rights In the Age of Big Data? An Overview of Trends and Developments In Consumer Privacy Class Actions

- Keynote Address: a Conversation With the Honorable Kathryn Mickle Werdegar, Justice of the California Supreme Court

- Major League Baseball Is Exempt From the Antitrust Laws - Like It or Not: the "Unrealistic," "Inconsistent," and "Illogical" Antitrust Exemption For Baseball That Just Won't Go Away.

- Masthead

- Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide: In the Age of Big Data Is Data Security Possible and Can the Enforcement Agencies and Private Litigation Ensure Your Online Information Remains Safe and Private? a Roundtable

- St. Alphonsus Medical Center-nampa and Ftc V St. Luke's Health System Ltd.: a Panel Discussion On This Big Stakes Trial

- St. Alphonsus Medical Center - Nampa, Inc., Et Al. and Federal Trade Commission, Et Al. V St. Luke's Health System, Ltd., and Saltzer Medical Group, P.a.: a Physicians' Practice Group Merger's Journey Through Salutary Health-related Goals, Irreparable Harm, Self-inflicted Wounds, and the Remedy of Divestiture

- The Baseball Exemption: An Anomaly Whose Time Has Run

- The Continuing Violations Doctrine: Limitation In Name Only, or a Resuscitation of the Clayton Act's Statute of Limitations?

- The Doctor Is In, But Your Medical Information Is Out Trends In California Privacy Cases Relating To Release of Medical Information

- The State of Data-breach Litigation and Enforcement: Before the 2013 Mega Breaches and Beyond

- The United States V. Bazaarvoice Merger Trial: a Panel Discussion Including Insights From Trial Counsel

- United States V. Bazaarvoice: the Role of Customer Testimony In Clayton Act Merger Challenges

- Restoring Balance In the Test For Exclusionary Conduct

RESTORING BALANCE IN THE TEST FOR EXCLUSIONARY CONDUCT

By Thomas N. Dahdouh1

The Federal Trade Commission’s recent monopolization cases against Intel2 and Google,3 two strikingly different recent decisions by Courts of Appeals — Novell v. Microsoft4 and ZF Meritor v. Eaton Corp.,5 and a recent article by Professor Herbert Hovenkamp6 all demonstrate the ongoing tumult in Sherman Act Section Two monopolization theory. Courts have struggled for some time now with the vague and circular test for Sherman Act Section Two cases, first enunciated in United States v. Grinnell Corp.7 Unfortunately, the line between exclusionary conduct and legitimate conduct cannot be delineated easily. Faced with the difficulty in assessing conduct in a fact-intensive and nuanced manner, some courts have sought "one-size-fits-all" tests that would allow a court to dismiss summarily meritless cases without engaging in fact-intensive investigation. Indeed, the Supreme Court’s decisions in Pacific Bell Telephone Co. v. linkLine Communications Inc.8 and Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko9 have certainly encouraged such efforts. The reality is that the near limitless variation of exclusionary conduct — and the serious potential that such conduct could seriously impair competition — makes any such effort to find a uniform test likely to lead to a seriously under-deterrent enforcement regime.

[Page 51]

Rather, the right enforcement approach must utilize a flexible balancing test. The District of Columbia Circuit Court, sitting en hanc in the Microsoft case, unanimously adopted the right overarching, rule-of-reason approach: a court must balance the anticompetitive effect of the exclusionary conduct against the procompetitive justification for the conduct.10 This article suggests a further addition to the overarching balancing test: namely, that the balancing test be adjusted depending on the type of exclusionary conduct at issue in the case. This article proposes that one would first (1) identify the type of conduct involved and slot it along a continuum from most suspect to least suspect; and then (2) adjust how demanding the "balancing test" is along the two key inquiries of the balancing test: (a) the level of evidence necessary to show that the asserted justification for the conduct is nonpretextual and cognizable (that is, procompetitive and efficiency-enhancing), and (b) the level of causal proof necessary to show that the conduct played a role in the creation or maintenance of the defendant’s monopoly power.

This article will first explain this approach in more detail, before turning to discuss in more detail the allegations in Google, the Novell and ZF Meritor decisions, and Professor Hovenkamp’s article on predatory pricing.

I. A CONDUCT-SPECIFIC BALANCING TEST

First, case-by-case adjudication by federal courts — and federal antitrust enforcement authorities — has developed implicit categories for exclusionary conduct from most to least suspect. The most suspect conduct includes the following:

- refusing to sell to a customer because the customer is also buying from a rival, as in Lorain Journal Co. v. United States;11

- treating a customer differently because it is a rival or would-be rival, as in the FTC’s first Intel case, FTC v. Intel Corp.;12

- "muscling" behavior — threats and tortious acts, including deceptive practices;13 and

[Page 52]

- entering into exclusives with customers that foreclose rivals from the most efficient distribution outlets, as in United States v. Dentsply International Inc.14

Nor far off would be conduct that falls in what has been termed "cheap exclusion." Cheap exclusion generally involves deception and tortious conduct.15 Exclusionary practices that are both inexpensive to undertake and incapable of yielding any cost-reducing efficiencies are "cheap" in both senses of that term and are most likely to appeal to a firm bent on maintaining or acquiring market power by anticompetitive means. Classic examples are instances of deception in the standard-setting process. For example, in Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc.16 the court held that a standard-setting participant’s false promise to license its patents that would read on the proposed standard could make out a monopolization claim. Another example is the Conwood case.17 In that case, the plaintiff had adduced evidence that the monopolist had engaged in a wide range of tortious conduct, including removing retail display racks with competitors’ products without retailers’ permission, providing misleading information to retailers about competing products and entering into exclusive agreements with retailers to exclude products.18

In the middle are near-exclusives, loyalty discounts or significant conditional discounts that lead to de facto exclusivity. These practices — commonly referred to as "minimum share discounts" — were part of the concerns that formed the basis of the second Intel case brought by the FTC.19 In Intel, the Commission found suspect the significance of the minimum share discounts involved — so-called "all unit" or first unit" discounts that were so large that relatively miniscule reductions in purchases could result in the loss of all the discounts.20 Indeed, the OEM computer customers often

[Page 53]

needed these discounts simply to remain profitable in a particular market segment.21 The Commission also objected to the conditions placed on some of the discounts.22

Also in the middle of the exclusionary continuum are claims that a manufacturer has created technological incompatibilities for interconnections with complementary products. In this second Intel case brought by the FTC,23 the Commission indicated that Intel had crossed the line by generating incompatibilities in the "bus" — the connection that allowed the graphics chip to work together with the microprocessor — that would preclude competitors’ previously-compatible graphics chips from working together with Intel’s future microprocessors.24 In that regard, the Commission alleged that Intel perceived the graphics chips manufacturers as a threat to Intel’s microprocessor monopoly, as well as competition in the graphics chip market.25

There is a fine line between issues relating to designing features and capabilities of a product that somehow adversely affect a rival or potential rival and incompatibilities in interconnections. The latter — suddenly ending a voluntary and presumably profitable course of enabling interconnections — may suggest that the change constitutes a deliberate effort to deter competition, particularly where the complementary product maker was poised to threaten the defendant’s monopoly market. As described later in this article, the issues in its Google decision fell more in the first category, while the issues that the FTC grappled with in its 2009 Intel action sounded squarely in the second.

In the FTC’s Google investigation,26 certain companies alleged that Google’s redesign of its search engine result page reduced the prominence in the display of their results. Design changes that have some adverse effect on other companies are, to my mind, much more difficult to challenge than technological incompatibilities. This is simply because valid business justifications are more likely for design

[Page 54]

changes that may make a product more desirable for consumers.27 Consequently, design improvements are at the least-suspect end of the continuum. Courts have demonstrated some level of hostility to requiring a monopolist to design the features and capabilities of its own products to allow competitors to compete more effectively.28

Following this continuum as outlined above can give a court a better sense of how to assess the particular conduct at issue. A court can fit the alleged conduct along this continuum and then assess it further. In the figure below, I have arrayed the different types of exclusionary conduct. A court could then employ a sliding scale for the balancing test focused on two key metrics: (1) assessing the asserted business justification for the conduct; and (2) assessing the causal link between the conduct and the creation or maintenance of the company’s monopoly power.

Assessing the Business Justification for the Conduct: The D.C. Circuit in Microsoft described how to assess any procompetitive justification for the conduct. First, the justification must be "nonpretextual" — that is, there must be some basis in evidence to support the claimed justification — and, second, the justification must

[Page 55]

be cognizable — that is, it must provide a "great[] efficiency or enhanced consumer" benefit.29 It is fairly easy to adjust these two key assessments and vary their strength, depending on how suspect the conduct is.

For conduct at the more suspect level, a greater quantum of evidence that the justification is non-pretextual may be necessary. For example, an adjudicator could require not just testimony supporting the claim of business justification, which may be self-serving, but also contemporaneous documents justifying the conduct at the time it is implemented. Similarly, to the extent that the conduct falls into the less-suspect end of the spectrum, a lower standard of proof may suffice.

On the issue of cognizability, one can similarly construct an array of different levels of proof. For example, at the more suspect level, one might require that the conduct be narrowly tailored to achieve the efficiency or enhanced consumer benefit. If less restrictive alternatives exist to achieve the same benefits, then the conduct can be condemned. As one moves toward the less suspect end of the spectrum, one could drop the requirement that the conduct be narrowly tailored. Even if there are other easily achievable methods to gain the efficiency goal, particular conduct might be acceptable, so long as it does in fact logically advance an efficiency-enhancing or beneficial-to-consumers goal.

Adjusting the Appropriate Level of Causal Proof: Causation is a trickier matter. The DC Court in Microsoft stated that it would not require the plaintiff to prove that the conduct caused or maintained the monopoly power. The Court pointed out the difficulty of proving what would have happened in the absence of the defendant’s exclusionary conduct: "neither plaintiffs nor the court can confidently reconstruct a product’s hypothetical technological development in a world absent the defendant’s exclusionary conduct."30

Indeed, the D.C. Circuit itself later mistakenly utilized a heightened causal test to wrongly dismiss monopolization claims. In Rambus Inc. v. FTC,31 the court ignored its prior holding in Microsoft and required that the FTC prove that, "but for" Rambus’ deception during a standard-setting process that it had no patents (or pending patent applications) that read on a proposed technological standard, the standard-setting body would have picked another standard. As explained by scholars, such a daunting test is inappropriate for exclusionary claims of deception, as for nearly every other aspect of exclusionary conduct.32 A test requiring a plaintiff to prove what would have happened absent the exclusionary conduct would frankly snuff out any challenge to exclusionary practices by a monopolist, rendering Section Two a statutory nullity. In a way, the test would be similar to a requirement that

[Page 56]

is sometimes advanced by defense counsel in monopolization cases that a plaintiff must show that the conduct in question had an effect on price. Again, given the impossibility of reconstructing a hypothetical world without the conduct, such a requirement should be rejected out of hand.

Rather, as the DC Circuit held in Microsoft, it is sufficient that the plaintiff show that the conduct is of a type reasonably appearing capable of making a significant contribution to the creation or maintenance of the company’s monopoly position.33 But, even as to this standard, there can be gradations of proof. For example, at the more suspect end of the spectrum, it may be sufficient to show that the conduct in question is similar to practices that have been condemned in other contexts as potentially exclusionary. In the middle, a plaintiff might need to show a bit more, such as how, as a matter of logic, the conduct in question could potentially undermine a rival’s threat to the monopolist’s market share.34 At the least suspect end of the spectrum, one would want even more: for example, some evidence that the monopolist acted because it perceived that its monopoly was threatened or thought that the conduct could help it in some way in attaining or maintaining its monopoly.

Applying These Two Metrics in a Balancing Context: For the most suspect types of conduct, one would likely want to see a heightened showing of business justification in contemporaneous documents. One would also want to see evidence that the conduct at issue was narrowly tailored to achieve the demonstrated business justification. A similar test should be applied to most forms of cheap exclusion.

For issues in the middle ground, one would want to apply a moderate level of scrutiny on the asserted business justification for the change. For example, concerning technological incompatibilities, if an alternative design that was relatively easily available could have kept the connection intact and there was evidence — from internal documents — that the change was done, in part, to forestall competition in the monopoly product by producers of complementary products, then the change should be condemned. But if the alleged consumer benefit could not have been just

[Page 57]

as easily improved without terminating the interconnections, then the change should not be condemned.35

Similarly, minimum share discounts also fall in the middle ground. The key question here is whether such discounts are structured so as to effectively foreclose the most efficient channels of distribution by rivals or otherwise dampen competition significantly.36 The test should not be the Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp.37 predatory pricing test — a showing of prices below Average Variable Cost ("AVC") during the predation period as welk as proof that the predator will likely recoup any lost profits thereafter — because that test does not focus on the particular harm from near-exclusives like these. Although, as we will see in the ZF Meritor decision, this question is not free from controversy, discounts that are tied to a company achieving a certain percentage of their purchases from the monopolist must be assessed for their foreclosure effect from the conditions on the discount, not the price effect of the discount itself. That is, the fact that a minimum share discount is not below average variable cost should not matter to the analysis; rather, the test should focus on the practical effect that the aggregation of such contracts has on the ability of rivals to access the most efficient channels of distribution.

Moreover, the test must not be the same as the test for total exclusives. Exclusives — because of their higher potential for foreclosing rivals — require a much higher showing of business justification. For example, one would want to see contemporaneous documentation of any asserted justification before clearing long-term 100% exclusives by a monopolist. By contrast, there may be cognizable business justifications for minimum share discounts. For example, economic literature suggests that a seller may be able to use minimum share discounts to induce its distributors to work harder to sell the seller’s product, by providing customers with additional information.38 One would still require some documentation of the efficiency justification, though, in order to forestall the possibility that the justification was

[Page 58]

pretextual. Nevertheless, some evidence that the monopolist was motivated in part by such legitimate reasons would go a long way.

By contrast, at the least suspect end of the spectrum, for conduct such as product design issues, an adjudicator should employ a less exacting balancing test. Again, as explained earlier, the design issues discussed here are changes in features or attributes of products, not technological incompatibilities between complementary products. In this area, the fact that consumers view a particular design as an improvement should suffice as a business justification and end any further analysis. Indeed, if the design makes a significant improvement in efficiency or otherwise lowers cost, that should be sufficient to clear it of further scrutiny. One could also posit that a heightened causal link would be necessary before condemning it. That is, one would want to see evidence that, in some way, the design logically helped the monopolist to attain or maintain its dominant position.

* * *

With this general discussion regarding assessing exclusionary claims, we can better examine three recent decisions concerning monopolization issues and an important scholarly work about predatory pricing. First is the FTC’s investigation concerning claims of exclusionary conduct against Google. Second is the Tenth Circuit’s recent decision in Novell. Third is the Third Circuit’s decision in ZF Meritor. Finally, this article examines a call for a reexamination of Brooke Group’s tough standard for challenging predatory pricing by Professor Hovenkamp.

II. GOOGLE

By any estimate, Google has monopoly power in general search — its only real competitor is Bing!, which has struggled since Microsoft introduced it.39 In 2009, complainants began to raise questions about Google’s practices. These companies claimed that Google unlawfully promoted its own "Google Product" products (or Universal Search results; also sometimes called "One Box") on its search results page at the expense of its rivals, and demoted rivals’ products on its search results page in order to maintain a monopoly over the fields of general search and search advertising.

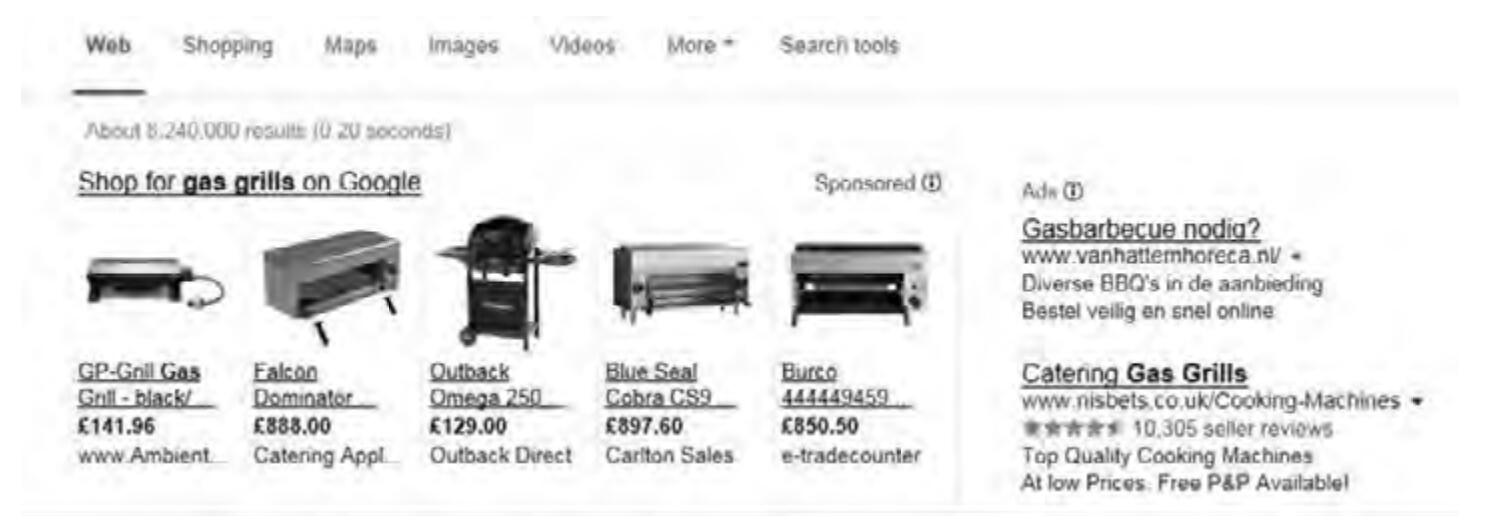

An example of a "One Box" that Google used is below. The box was usually positioned within the first two or three of the results on the search results page.

[Page 59]

The theory advanced by Google’s rivals to the Federal Trade Commission staff investigating Google’s conduct was similar to the theory advanced in the Microsoft case. In that case, Microsoft acted to block a "nascent threat" to its monopoly (over operating systems) from a different kind of technology (browsers).40 Similarly, in Google, the theory was that Google’s vertical rivals (those websites that offer search capabilities in niche categories, such as consumer products, local services, and travel — websites like TheFind, NexTag, Expedia, etc.), collectively, represented a "nascent threat" to Google’s power over the fields of general search and search advertising. While none of these vertical rivals, alone, could constrain Google’s monopoly, they allegedly served collectively to threaten the most valuable parts of Google’s search portfolio — the areas of search that are typically the most lucrative from an advertising standpoint. At its core, then, this alleged "nascent threat" was the provision of an alternative advertising platform that could erode or constrain Google’s ability to charge monopoly prices for search advertising. To reduce or eliminate this threat, the story goes, Google sought to handicap these "verticals."

As the Commission examined these claims, it became clear that, while Google understood that vertical search engines could possibly take customers away, there was absolutely no support for the notion that Google instituted the algorithm changes, in whole or in part, because of this perceived threat from vertical search engines. Google instituted the "Universal Search" or "One Box" because its contemporaneous studies showed that consumers liked them. Every iteration of its algorithm changes — including every change to the Universal Search or One Box—was vetted by users carefully and fairly, and these contemporaneous, legitimate business reasons for the changes would have been nearly insurmountable to challenge, given antitrust’s general hostility to challenges to product design changes. The fact that Google’s competitor, Bing!, had been using Universal Searches and "One Boxes" would have made a challenge even more difficult.

As a result, the Commission chose not to challenge Google’s design changes to its algorithm.41 However, two other aspects of Google’s conduct raised more troubling antitrust issues. Google agreed to cease its practices with respect to these.

First, Google, in at least two instances, "scraped" or copied the user-generated content on two rival local and travel sites — Yelp and TripAdvisor. In contrast to its search algorithm changes, Google did not improve this content — it merely took the content virtually wholesale and used it for its own offerings. It appeared that Google was doing this to self-start its own user reviews on its proprietary local and travel sites, where it sold various goods and services, not for its general search results business. It is no surprise that consumers generally prefer placing comments on sites that already contain voluminous comments.

Google did not remove Yelp’s contents on Google’s proprietary local and travel sites despite repeated requests from Yelp to do so. At one point, Google indicated that the only way for it to do so would be to stop crawling Yelp’s website for links, which would have effectively crushed Yelp’s business as Yelp would no longer have appeared in general

[Page 60]

search results. In the Commission’s statement on Google, the majority expressed concern that, left unchecked, Google’s scraping of content from rival sites for its own proprietary sites could undermine incentives to innovate on the Internet.42

If the 800-pound gorilla in the Internet world could freely take any content that is intellectual property-protected to use on its pages where it is selling its own products and services (as opposed to using it as part of its general search business), they said, innovation could potentially be chilled on the Internet.43 Google’s threats to delist these rivals entirely from Google’s search results when they protested the misappropriation of their content were even more egregious. In other words, the majority believed Google was using its power over search to extract something from an unwilling party.

Second, Google had limited the ability of advertisers to advertise simultaneously on Google and competing search engines through the means of restricting application program interfaces ("APIs") on Google’s advertising tools. While larger businesses used their own advertising tools, smaller businesses were more reliant on Google-made advertising tools. Going back to the catalog of monopolistic conduct, this behavior is similar to a monopolist placing restrictions on buyers’ ability to purchase from the monopolist’s rivals. As such, this conduct merits serious concern. Two Commissioners advocated for relief here,44 and Google voluntarily agreed to change its behavior on this issue as well.

Overall, I believe the Commission’s action in Google demonstrates it applies a careful, conduct-specific balancing test when assessing whether particular conduct violates Section Two.

III. NOVELL

Novell, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.,45 by contrast, shows the dangers of courts and antitrust enforcers seeking to apply a "one-size-fits-all" test for monopolization claims.

In this case, WordPerfect claimed that Microsoft, just prior to the launch of Windows 95, withdrew certain APIs that WordPerfect needed to allow its applications to compete effectively against Microsoft’s Office suite. WordPerfect’s effort to challenge this as exclusionary conduct affecting the applications market was time-barred. However, because of the government’s action against Microsoft’s exclusionary efforts vis-a-vis its operating system market position, WordPerfect could still make a claim that this withdrawal of APIs improved Microsoft’s monopoly over its operating system.46

The Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit rejected this claim, finding it impossible to imagine that this withdrawal was exclusionary. The Court found that the act was not exclusionary because it failed the short-term profit sacrifice test, which assesses whether

[Page 61]

particular conduct is profitable in the short term. Because the withdrawal of the APIs from rivals such as Novell improved Microsoft’s own profits in word processing applications, there was no sacrifice of short-term profits. Thus, it was not exclusionary, the court reasoned.47 The decision goes on at some length about the dangers of over-enforcement with respect to technological incompatibilities.48 Interestingly, however, the Court fails to cite one court decision in favor of a plaintiff that it felt was unjustified.

One can look throughout this extremely long opinion and not find one mention of any procompetitive reason for Microsoft’s withdrawal of the APIs — for example, any claim that this withdrawal made Microsoft Word or Microsoft Office a better product for consumers.49 Rather, there is a starkly anticompetitive quote from Bill Gates, then CEO of Microsoft, in contemporaneous documents that the withdrawal was done precisely to undercut rivals.50 Nor is there any mention of the D.C. Circuit’s seminal decision in Microsoft and its requirement that a court assess the exclusionary nature of the conduct, the procompetitive justifications for the conduct, and then weigh them against each other.

The Bush Administration has advanced a somewhat similar standard of "no economic sense" for refusals to deal. 51 The notion underlying this test is that the conduct would have to make no economic sense for the defendant before it could be condemned as exclusionary.

These tests all seem to want to import the logic of Lorain Journal and apply it across the board to a wide variety of conduct. Lorain Journal involved refusing to sell to a customer because that customer is buying from a competitor.52 It is the monopolist equivalent of cutting off your nose to spite your face. It is relatively easy to assess — it sacrifices short-term profits; there is generally no justification for the conduct; and an adjudicator does not need to do much more analysis to conclude that the harm outweighs the benefit.

There is language in Trinko53 that could lead one to think that such a test should be applied more broadly, but I do not think the opinion in Trinko supports such a crabbed notion of exclusionary conduct. In Trinko, the Court emphasized the fact that,

[Page 62]

in Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., a case where the plaintiff prevailed, the defendant sacrificed profits by terminating what had been a profitable joint ticket package for access to its ski resorts as well as its competitors’.54 But, as one thoughtful commentator has pointed out, Trinko’s "observation that Aspen’s sacrifice of profits evidences its anticompetitive intentions . . . is a far cry from a wholesale endorsement of ‘sacrifice’ as a necessary condition for" liability.55 Indeed, the court goes on at length in Trinko to emphasize the facts in that matter — namely, that "the complaint there never alleged that Verizon voluntarily engaged in a course of dealing with its rivals, or would have ever done so absent statutory compulsion."56 Moreover, as the Court further noted, the "services allegedly withheld are not otherwise marketed or available to the public."57 In other words, the Court focused not only on the lack of short-term profit sacrificing, but the entire factual situation, most particularly the glaring fact that the plaintiff wanted the defendant to do something it had never done at all.

Indeed, the consequence of such standards as the "no economic sense" and "profit sacrifice" tests will be seriously underdeterrent. As noted above, cheap exclusion does not sacrifice short-term profits, but can be quite exclusionary. A particularly pernicious example comes from the FTC’s 2009 case against Intel challenging Intel’s deception regarding its compiler.58 Intel marketed its compiler — which sits on top of software and interacts with the microprocessor — as working well with all types of microprocessors, including those of its only real rival, Advanced Micro Devices ("AMD"). But Intel designed its compiler to check what company’s microprocessor was working on a particular computer. If the check showed that the computer had an AMD chip, the compiler would slow the software down significantly, degrading the speed and performance of the computer. This was cheap, and its effects were devastating to competition from AMD. Software developers and independent testing groups routinely found AMD chips to perform significantly worse than Intel chips did, even though, without the ruse, the AMD chip may have performed better than Intel’s. Indeed, it took years and large expenditures for software developers and AMD to uncover what was happening. Because so much of microprocessor marketing depends on independent and third-party testing that evaluates performance claims and because the best profits are made early upon introduction of a new product, Intel’s deception concerning its compiler seriously undermined AMD’s sales for a significant period of time.59

Novell involved a situation different from and more complicated (in my view) than cheap exclusion. Nevertheless, I would posit that this type of deliberate technological incompatibility, with no valid business justification, can also have serious anticompetitive consequences. Microsoft first offered the APIs, leading companies like WordPerfect to

[Page 63]

design their software to be compatible with it, but later pulled the APIs.60 This pulling the rug out from under partners that may become competitors,61 after those partners have invested in what they thought was a set standard, is exactly where technological incompatibilities can have their most devastating impact on would-be rivals. It is similar to the Intel FTC case regarding the bus between the graphic chip and the microprocessor.62 In both instances, the monopolist made a voluntary decision to cooperate and then reneged. In both instances, the competitive consequences of such radical changes in technology markets, where virtually everything interacts with everything else and long lead times (and huge sunk investments) are required to bring products to market.

Nevertheless, the Tenth Circuit’s decision in Novell shows the powerful pull of "one-size-fits-all" tests for exclusionary conduct under Section 2. Federal courts feel ill at ease deciding these types of cases, and are looking for an easy test.

Another variant on the short-term profit sacrifice test has been suggested by Judge Posner: namely, testing whether the conduct would foreclose an equally-efficient competitor.63 Now the "equally-efficient competitor foreclosure" test is more nuanced than the short-term profit sacrifice or "no economic sense" tests. Yet it is rare that, in a problematic market, a rival to a monopolist (with seventy plus percent market share) will enjoy the same economies of scale and scope as the monopolist. Exclusionary conduct can foreclose a significant part of the market (for example, the most efficient distribution channels) while leaving the hypothetical "equally efficient" competitor with enough theoretical space to compete. Moreover, as described below, the proper test is not whether there is sufficient room for a rival to somehow survive, but rather whether there is space for the rival to pose a serious threat to the defendant’s monopoly. The "equally efficient competitor" test does not address this issue.

IV. ZF MERITOR

The Third Circuit’s decision in ZF Meritor v. Eaton Corp.64 concerned defendant’s market share and related discounts and rebates for its heavy-duty truck transmission products, which were found to be exclusionary conduct that violated the antitrust laws. The majority viewed the contract implementing the discounts and rebates as de facto exclusive dealing. They focused, in particular, on three aspects of the contracts: (1) the contracts had market share "targets" that the OEM buyer purchase up to 92% of their requirements from the defendant, with the defendant allowed to terminate or force the buyer to give back all discounts if the targets were not met; (2) the contracts mandated that the buyers advertise defendant’s transmissions as its standard offering in its data books, and two of the four contracts mandated that the buyer remove rival products

[Page 64]

from its listings; and (3) the contracts mandated that defendant’s products be offered to the buyers’ customers at a preferential price, which, the evidence showed, was achieved by raising the price of rival products.65 Locked into a less-than-10 percent share, rival ZF Meritor exited the market.66 The majority found these conditions to the contracts to violate Section Two.

This provoked a furious dissent from Judge Greenberg, pointing out several things: (1) while there were conditions placed on the contracts, these were not 100% exclusives; (2) the market share targets were not absolute contractual requirements; and (3), most importantly in his view, the contract price terms were always above cost.67 For Judge Greenberg, plaintiffs were trying to re-label what was really an objection to the defendant’s prices as objections to the conditions placed on those contracts. For Judge Greenberg, the matter should have been analyzed under the Supreme Court’s Brooke Group68 predatory pricing precedent, and, since the pricing was always above-cost, the complaint should have been dismissed.69

The majority’s focus on the realities of the contracts at issue — rather than a more formalistic view — makes more sense. The majority was correctly focusing on the "practical effect" resulting from the contracts at issue.70 That is, although the contracts were not expressly exclusive, the defendant had the right to terminate the agreements if the market share targets were not met, and, while it did not ever invoke that right, the OEMs thought that Eaton might cut them off. Because of Eaton’s dominant position, the consequences of termination would be devastating to any OEM. As the court put it, "the OEMs had a strong economic incentive to adhere to the terms of the [agreements], and therefore were not free to walk away from the agreements and purchase products from the supplier of their choice."71 Moreover, while the targets were not 100%, the court rightly focused on the fact that the portion of the market that was foreclosed effectively impeded rivals from gaining the "’the critical level necessary’" to pose a real threat to the defendant’s business.72 In this regard, because Eaton had agreements with the four largest OEMs, the effect was to exclude rivals from access to the lion’s share of these critical buyers.

Another aspect of Eaton’s defense in the litigation that the majority rightly rejected was the notion that, because the OEMs testified that they were not coerced or compelled to enter into the contracts at issue, these deals could not be anticompetitive. Indeed, in his dissent, Judge Greenberg emphasizes that the OEMs were not opposed to these contracts.73 A mantra often heard in monopoly investigations is that the intermediate

[Page 65]

distributor customers — be they OEMs or retailers — are not averse to the contracts in question. Intermediate distributors facing upstream monopolists, however, may not be good representatives for the consumers who ultimately face the anticompetitive consequences of the monopolist’s conduct. The key concern of intermediate distributors facing an upstream monopolist is their competitive condition vis-a-vis their direct competitors — other intermediate distributors. In fact, if nearly all intermediate distributors are facing similar conduct by the monopolist, it will likely be relatively easy for the intermediate distributor to pass on the "cost" of the monopolist’s conduct to end-users. Indeed, economic literature suggests that loyalty discounts may be used to increase the profits earned by the entire vertical chain of production — that is, both the upstream monopolist and intermediate distributors, to the detriment of consumers.74 Consequently, the court was right to focus on the practical economic incentives resulting from these contracts, rather than on whether or not intermediate distributors felt threatened or were unhappy with the contracts.75

The majority also focused on another key aspect of these agreements, namely the provision barring OEMs from providing defendants’ rivals’ information in OEMs "data books," which OEMs use to advertise their products to downstream truck buyers. The majority noted testimony that an OEM’s data book was the "most important tool" that any buyer selecting component parts for a truck would use: if a product was not listed in a data book, it was "a disaster for the supplier." 76 This aspect of the contracts in Eaton is not all that dissimilar from Lorain Journal, in that this restriction was aimed squarely at precluding OEM customers from purchasing Eaton’s rivals’ products. And, frankly, what was the business justification for Eaton insisting that the OEMs effectively hide products that they were trying to sell? In many ways, this restriction is similar to a restriction Intel imposed on one of its OEMs, Hewlett-Packard ("HP"), when it got HP to agree not to bid a computer product with Intel rival AMD’s chip in it to a customer unless the customer specifically asked for it.77

[Page 66]

Ultimately, the majority got it right when it focused its inquiry on whether the restrictions all told would prevent a rival from "’pos[ing] a real threat’" to defendant’s monopoly."78 It is this last point that is really the rejoinder to arguments by some that the focus of foreclosure analysis should be on whether the extent of foreclosure would bar an equally-efficient competitor from competing. Proper Section Two enforcement should not be focused just on whether exclusionary conduct still leaves a rival with enough breathing room to struggle along on the margins. Rather, the proper focus is on whether the exclusionary conduct effectively barricades rivals into the least profitable segments of a marketplace precisely to make it impossible for that rival to pose a real threat to defendant’s monopoly position.

For example, in the Intel situation, the various restrictions Intel imposed did not drive AMD out of business. What they did do, however, was forestall AMD from breaking out of its small market share when it had the competitive edge over Intel in its technology. As detailed in both the FTC’s and New York Attorney General’s complaints against Intel,79 AMD, in the 2002 time frame, had developed a uniquely attractive Hammer microprocessor technology that offered commercial end users — a segment of the market AMD had not been successful in —the benefit of higher performance while still being able to run legacy systems. This value proposition could have given AMD the ability to break into and gain significant market share in the highly profitable commercial segment of the computer marketplace. Intel’s various modes of exclusionary conduct, however, gave it the ability to effectively constrain AMD’s market share rise and thereby rob it of its ability to break out of its then-small market share.

V. HOVENKAMP’S ASSAULT ON BROOKE GROUP

No less an authority than Professor Hovenkamp has called for a re-examination of the Brooke Group standard in a recent article, The Areeda-Turner Test for Exclusionary Pricing: A Critical Journal.80 The predatory pricing test as enunciated by the Supreme Court in Matsushita Elec. Industrial Co., Ltd. v. Zenith Radio Corp.81 and later clarified in Brooke Group requires two things. First, the plaintiff must show a market structure and arrangement of firms such that the predator could rationally have predicted that the predatory pricing strategy would be profitable. This is the notion of recoupment — that is, that the defendant could reasonably expect to be able to recoup losses from its predatorily low prices. Second, the plaintiff must show that the defendant’s prices over a significant number of sales were below a relevant measure of cost, presumptively average variable cost ("AVC").

In his article, Hovenkamp first describes three key critiques of Brooke Group from economists: (1) AVC – is a poor surrogate for short-run marginal cost; (2) the test is

[Page 67]

seriously underdeterrent in markets with high fixed costs, which are markets most conducive to exclusion by strategic pricing; and (3) short run measures such as AVC are poor measures of strategic predatory pricing, which may be long-term.

Hovenkamp specifically criticizes the Department of Justice’s loss in United States v. AMR Corp.,82 where the DOJ was unsuccessful in seeking to include in variable cost the foregone profit of having the airplane serve a route different from the predatory route.

He also questions the recoupment requirement, and advocates instead that the ordinary structural requirements for monopolization (dominant firm, high entry barriers, customers insensitive to price increases) should suffice. Hovenkamp also points out that predatory pricing may be a mechanism to ensure conformity to a cartel’s or oligopoly’s price terms. He also suggests that the average variable cost standard should be amended in certain respect, particularly to include foregone profits of alternative uses, as the Department of Justice sought to do in the American Airlines case.

VI. WOULD A UNIFORM TEST IMPROVE THE ADMINISTRABILITY OF SECTION TWO?

The greatest policy argument for imposing uniform tests is that, otherwise, there will be a huge "cost to the economy," as Judge Greenberg’s dissent ominously intones.83Monopolists will pull their punches, and customers of monopolists will face higher prices. But, as Professor Hovenkamp has pointed out, more uniform tests do not necessarily mean greater ease of administrability. In the context of predatory pricing cases, there are huge problems in following the Brooke Group pricing test. For example, as described by Professor Hovenkamp, how does a court calculate average variable cost when companies are selling multiple products, when significant capital costs are involved, and when depreciation must be factored in?84 There is no guarantee that the "short-term profit sacrifice" or "equally efficient competitor" test is going to be any easier to administer in the non-price predation area. Does one examine only short-term profits from the market being monopolized, for example, or does one include short-term profits in other markets? How does one define profit? Does it include lost opportunity cost? Similarly, for the "equally efficient competitor" test, how does one calculate the efficiency of a company? If, for example, a monopolist has locked up through exclusives the most efficient distribution channels, how does one decide that the remaining distribution — areas that the monopolist has foregone seeking exclusives for — is going to be sufficiently profitable for an equally efficient competitor?

Furthermore, there is a lack of reality in these tests. One can understand that there are costs to rules that increase enforcement against price predation and against design improvements that foreclose competitors. But what are the "costs" to rules that proscribe "muscling" behavior such as destroying competitor racks in Conwood or deceiving software developers, as in the compiler part of the FTC’s second Intel case? Indeed, what

[Page 68]

are the costs to barring Google from vacuuming up competitor’s content on the Internet and using it to sell its own paid services?

This brings us to the fundamental question Professor Hovenkamp asks in his piece. He is writing about predatory pricing standards, but I would posit that it applies equally well to other areas of Section Two law: These tests "require antitrust enforcers to surrender a great deal of territory on the promise of a rational test that is more capable of being administered. But if ease of administration is in fact elusive, then perhaps we are giving up too much and should develop . . . [rules] that [are] more receptive to plaintiffs."85 In the area of predatory pricing, he notes that only one predatory pricing plaintiff has ever made it past summary judgment in the over twenty-years that Brooke Group has been in the law.86 One could similarly note that, in the area of Section Two enforcement generally, there are very few plaintiff victories either. There have been only a handful of matters — Conwood, LePage, ZF Meritor, and Microsoft — that, in recent memory, can be viewed as plaintiff wins in federal court. Are we sure that monopolistic practices are so rare?

Moreover, and this is important, a plaintiff does not even make it to the point that the exclusionary conduct is assessed before showing that the defendant has monopoly power, that is, "the power to control prices or exclude competition."87 The showing of monopoly power is no easy feat. A plaintiff must define a proper relevant market, show that the defendant has a market share in that market that is north of 70% (or show direct evidence of market power) and prove that that market position is a durable one, such as through showing high barriers to entry in that relevant market. Given all of these high initial hurdles — all of which are relatively easier-to-assess and administer in order to prevent false positives, it is difficult to fathom why some type of uniform simplified test for assessing the exclusionary conduct itself is so necessary.

Rather than formalistically applying one-size-fits-all rules that lead to serious under-deterrence, the better approach is the case-by-case approach — the common law approach — that the Supreme Court has enshrined as the touchstone of antitrust jurisprudence since the Standard Oil88 case. After all, courts have repeatedly said that Section Two analysis is similar to the Rule of Reason analysis employed for Section One.89 The standard under the Rule of Reason is quite a broad one. By contrast, do we really need so many artificially applied uniform tests to prevent overenforcement in the Section Two context? Rather, by carefully analyzing and categorizing conduct — and adjusting various metrics based on that categorization — courts and enforcers can better strike a balance that provides guidance for business at the same time that it provide deterrence against anticompetitive conduct.

[Page 69]

——–

Notes:

1. Regional Director, Western Region, Federal Trade Commission. The thoughts expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not reflect the views of the FTC, any Commissioner or anyone else. This article was developed from talks given at the Los Angeles County Bar Association in December 2013 and at the Golden State Antitrust Institute in San Francisco in October 2014.

2. Complaint, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (F.T.C. Dec. 16, 2009), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9341/091216). The matter was settled through a consent agreement, issued in 2010. Decision and Order, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (F.T.C. Oct. 29, 2010), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9341/1001102inteldo.pdf.

3. Statement of the Federal Trade Commission Regarding Google’s Search Practices, In the Matter of Google Inc., No. 111-0163 (F.T.C. Jan. 3. 2013), http://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2013/01/statement-federal-trade-commission-regarding-googles-search-practices. All of the Commissioner’s statements regarding the Google investigation are available online. F.T.C., Google Agrees to Change its Business Practices to Resolve FTC Competition Concerns in the Markets for Devices Like Smart Phones, Games and Tablets, and in Online Search (Jan. 3. 2013), http://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2013/01/google-agrees-change-its-business-practices-resolve-ftc.

4. 731 F.3d 1064 (10th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 2014 U.S. LEXIS 2960 (Apr. 28, 2014).

5. 696 F.3d 254 (3d Cir. 2012).

6. Herbert J. Hovenkamp, The Areeda-Turner Test for Exclusionary Pricing: A Critical Journal, U. Iowa Legal Studies Research Paper No. 14-16 (Apr. 2014), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2422120.

7. The test is whether a company has monopoly power (which generally requires a market share above 70% as well as high barriers to entry) and has engaged in "willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident." United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570-71 (1966); see also Einer Elhauge, Defining Better Monopolization Standards, 56 Stanford L. Rev. 253 (2003).

8. 555 U.S. 438 (2009).

9. 540 U.S. 398 (2004).

10. United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34 (D.C. Cir. 2001), cert. denied, 534 U.S. 952 (2001).

11. 342 U.S. 143 (1951) (holding unlawful monopoly newspaper’s decision to refuse to accept advertising from companies that were also buying advertising time from rival radio station).

12. 128 F.T.C. 213 (1999) (challenging, inter alia, Intel’s refusal to sell microprocessors to computer Original Equipment Manufacturer ("OEM") customer Digital Equipment Corporation because Digital had sued Intel for patent infringement in microprocessors; Digital at the time was developing a rival microprocessor architecture that could have threatened Intel’s monopoly).

13. Conwood Co. L.P. v. U.S. Tobacco Co., 290 F.3d 768 (6th Cir. 2002) (finding that monopolist violated Section Two, by, inter alia, removing rival retail display racks without retailers’ permission and providing misleading information to retailers about competing products). See generally Maurice E. Stucke, When a Monopolist Deceives, 76 Antitrust L. J. 823 (2010) (arguing that then-existing monopolization law theory was far too skeptical of the anticompetitive potential of deceptive practices by a monopolist).

14. 399 F.3d 181, 191 (3d Cir. 2005) (holding that de facto exclusive dealing arrangements with certain distributors that foreclosed the most efficient avenues for distribution violated Section Two).

15. Susan A. Creighton, D. Bruce Hoffman, Thomas G. Krattenmaker & Ernest A. Nagata, Cheap Exclusion, 72 Antitrust L.J. 975 (2005).

16. 501 F.3d 297 (3d Cir. 2007).

17. Conwood, 290 F.3d 768 (6th Cir. 2002).

18. Id. at 773-81. But see Joshua D. Wright, Antitrust Analysis of Category Management: Conwood v. United States Tobacco Co., 17 Sup. Ct. Econ. Rev. 311, 330 (2009) (arguing that the Sixth Circuit failed "to distinguish authorized from unauthorized product removal, or systematic product destruction from limited, one-time events, [and thus] allowed harm to a competitor to substitute for evidence of harm to competition").

19. Complaint 53-54, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (F.T.C. Dec.16, 2009), http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9341/091216).

20. Economic analysis explains that discounts that apply to all of the units that the buyer has purchased if and only if the buyer has met its volume or market share target can create a powerful incentive to meet or exceed the share target. Zhijun Chen & Greg Shaffer, Naked Exclusion with Minimum Share Requirements, 45 RAND J. of Econ. 64 (Spring 2014); Janusz A. Ordover & Greg Shaffer, Exclusionary Discounts (CCP Working Paper No. 07-13, (June 2007), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=995426.

21. Amended Complaint at 36, New York v. Intel Corp. (D. Del. Oct. 12, 2009) (No. 09-827) ("Dell’s quarterly profit margins depended on Intel’s payments"), available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/antitrust/legal-documents/people-v-intel-corporation; id. at 56-57 ("A senior [Hewlett-Packard] executive emphatically vetoed [a plan to buy more of Advanced Micro Devices Inc. chips], because without the ‘Intel moneys . . . we do not make it financially’: ‘You can NOT use the commercial AMD line in the channel in any country, it must be done direct. If you do and we get caught (and we will) the Intel moneys (each month) is gone (they would terminate the deal). The risk is too high. Without the money we do not make it financially. . . .’"). The New York State Attorney General later settled this action against Intel on Feb. 9, 2012.

22. In some instances, Intel required that the OEM only bid Intel-based computers, and offer Advanced Micro Device Inc. (AMD) based computers only if the end user affirmatively asked for AMD. See infra text at n. 77.

23. See supra at n. 19.

24. Complaint 75-91, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (F.T.C. Dec. 16, 2009), available at http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9341/091216).

25. Id.

26. See supra note 3.

27. There are certainly circumstances where a technological incompatibility occurs at the same time that a monopolist makes a design change. Those instances should be placed in the middle of the continuum, so that the court can fully balance the non-pretextual and procompetitive reasons of the design change fully against the harm to competition.

28. Berkey Photo, Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 603 F.2d 263, 286 (2d Cir. 1979) ("[A]ny firm, even a monopolist, may bring its products to market whenever and however it chooses.").

29. United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 59 (D.C. Cir. 2001), cert. denied, 534 U.S. 952 (2001).

30. Id. at 79.

31. 522 F.3d 456, 461 (D.C. Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 1318 (2009).

32. See generally Joel M. Wallace, Rambus v. F.T.C. in the Context of Standard-Setting Organizations, Antitrust and the Patent Hold-Up Problem, 24 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 661, 683-84 (2009) ("The central fault of the D.C. Circuit’s analysis was the misapplication of its own decision in Microsoft regarding the proof of causation necessary to support a claim of anticompetitive conduct.").

33. Microsoft, 253 F.3d at 79.

34. Indeed, a compelling argument can be made that, despite protestations to the contrary, intent evidence is a key part of any Section Two challenge. Intent evidence can be quite illuminating in revealing the exclusionary logic behind certain conduct. See Microsoft, 253 F.3d at 59 (intent evidence is relevant because it helps the court "understand the likely effect of the monopolist’s conduct."). The concern one hears about using intent evidence is that companies often use florid language in describing how they compete. This is really an overblown concern in the monopolization context, because a case must pass through so many threshold requirements before the court even makes it to assessing the nature of the conduct at issue. Moreover, courts are certainly adept at distinguishing between contemporaneous documents that trash talk generally and those that elucidate the anticompetitive logic behind decisions by a monopolist to employ certain conduct.

35. In this regard, it should be pointed out that the treatise Antitrust Law Development’s description of the state of the law here is out of line with the D.C. Circuit’s explicit balancing test standard it developed in the Microsoft decision and its holdings in that case. Indeed, the treatise only highlights the portions of the Microsoft decision where the court rejected challenges to technological incompatibilities, while oddly ignoring other parts of the decision — particularly with respect to Microsoft’s integration of its browser with the Windows operating system — where the court upheld challenges to Microsoft’s introduction of technological incompatibilities. See ABA Section of Antitrust Law, Antitrust Law Developments 272-73 (7th ed. 2012). It is clear that, in examining design challenges, the DC Circuit was in fact following a balancing test — assessing the benefits of the design changes against their anticompetitive potential — rather than simply blessing any design change Microsoft made.

36. Economic thinking supports the potential for minimum share discounts to be anticompetitive. Theoretical models have been constructed under which such minimum-share discounts can deny rivals sufficient outlets for their products. See supra note 20. Such contracts can also dampen competition among the competitors that are in the market. See Chen and Shaffer, supra note 20.

37. 509 U.S. 209 (1993).

38. David E. Mills, Inducing Downstream Selling Effort with Market Share Discounts, 17 Int’l J. of Econ. of Bus. 129 (Sept. 2010), http://economics.virginia.edu/sites/economics.virginia.edu/files/Inducing%20Downstream%20Selling%20Effort%20with%20Market%20Share%20Discounts.pdf.

39. Yahoo also has a search engine, but, since its search engine is run by Microsoft, it cannot be considered a separate competitor.

40. United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 78 (D.C. Cir. 2001), cert. denied, 534 U.S. 952 (2001).

41. Statement of the Federal Trade Commission Regarding Google’s Search Practices, In the Matter of Google Inc., No. 111-0163 (F.T.C. Jan. 3. 2013), http://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2013/01/statement-federal-trade-commission-regarding-googles-search-practices.

42. Id. at 3 n.2.

43. See id.

44. Id.

45. 731 F.3d 1064 (10th Cir. 2013), cert. denied, 2014 U.S. LEXIS 2960 (Apr. 28, 2014).

46. Id. at 1067-71.

47. Id. at 1075-81.

48. Id. at 1073-74.

49. The Court did seem to suggest that the result might be different if Novell could have challenged Microsoft vis-a-vis the applications market, but, given the logic of its opinion, it is not clear how that would have changed the result at all. As I note below, Novell and its WordPerfect were, at that point, serious challengers to Microsoft’s overall dominance. Indeed, Novell, with an entire suite of Office-type products, was uniquely positioned to partner up with operating system and browser competitors to challenge Microsoft’s dominance in operating systems.

50. In an October 3, 1994 email, Bill Gates, never one to mince words, explained: "I have decided that we should not publish these [APIs]. We should wait until we have a way to do a high level of integration [which] will be harder for the likes of Notes, WordPerfect to achieve, and which will give [Microsoft] Office a real advantage." 731 F.3d at 1069.

51. Brief for the United States and Federal Trade Commission as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioner, Verizon Commc’ns Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398 (2004) (No. 02-682), at 22 ("[C]onduct that would not make sense but for its tendency to reduce or eliminate competition" is required for actionable refusal to deal).

52. Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, 342 U.S. 143 (1951).

53. Verizon Communications, Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398 (2004).

54. Trinko, 540 U.S. at 408-11 (citing and discussing Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp. 472 U.S. 585 (1985)).

55. Andrew I. Gavil, Exclusionary Distribution Strategies by Dominant Firms: Striking a Better Balance, Antitrust L. J. 3, 58 (2004).

56. Trinko, 540 U.S. at 409.

57. Id. at 410.

58. Complaint ¶¶ 56-61, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (Dec. 16, 2009), http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9341/091216).

59. Id.

60. Novell, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp. 731 F.3d 1064, 1068-69 (10th Cir. 2013).

61. It bears reminding that WordPerfect, at that point in time, was then a strong competitor to Microsoft Word software, and could have easily joined with other competitors in helping to challenge Microsoft’s operating system monopoly.

62. Complaint 75-91, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (F.T.C. Dec. 16, 2009), http://www.ftc.gov/os/adjpro/d9341/091216).

63. Richard A. Posner, Antitrust Law 194-95 (2d Ed. 2001).

64. 696 F.3d 254 (3d Cir. 2012).

65. Id. at 263-68.

66. Id. at 267.

67. Id. at 303-53 (Greenberg, J., dissenting).

68. Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209 (1993).

69. 696 F.3d 254, 303 (3d Cir. 2012) (Greenberg, J., dissenting).

70. ZF Meritor, 696 F.3d at 282 (quoting Tampa Elec. Co. v. Nashville Coal Co., 365 U.S. 320, 326 (1961)).

71. Id. at 287.

72. Id. at 286 (quoting Dentsply, 399 F.3d at 191).

73. Id. at 338-39 (Greenberg, J., dissenting).

74. Roman Inderst & Greg Shaffer, Market-Share Contracts as Facilitating Practices, 41 RAND J. of EcoN. 709 (Winter 2010). In their model, the dominant upstream seller faces the problem of choosing a pricing policy that accomplishes the dual — and potentially conflicting — objectives of creating optimal pricing incentives for its downstream retailers and limiting the effect of competition from its upstream competitors. Minimum-share contracts can help to accomplish these goals by allowing the seller to increase its wholesale price to downstream purchasers above the competitive level while at the same time limiting the downstream purchasers’ incentive to shift purchases to competing sellers’ products due to the price increase because, for example, much or all of the price increase may be passed along to consumers. In this way, minimum share contracts increase the profits earned by the entire vertical chain of production, to the detriment of consumers.

75. A similar view often heard from intermediate distributors is that, even without the minimum-share contracts, they would not have purchased more rival products for resale. Intermediate distributors will often say that the contracts were "sleeves off a vest" in that their behavior would not have been different, even without the contracts. As explained earlier, it is virtually impossible for anyone — even savvy OEMs and retailers — to predict what would have happened but for the monopolist’s exclusionary conduct. It is no more relevant for the final analysis whether OEMs and retailers testify as to what they think they would have done without the contracts in place. This kind of "Monday morning quarterbacking" is precisely why the D.C. Court of Appeals in United States v. Microsoft warned against placing a heightened causation requirement into monopolization law.

76. ZF Meritor, 696 F.3d at 287-88.

77. Complaint at 53-54, New York v. Intel (D. Del. Oct. 12, 2009), http://www.ag.ny.gov/antitrust/legal-documents/people-v-intel-corporation.

78. ZF Meritor, 696 F.3d at 287-288 (citation omitted) (quoting Microsoft, 253 F.3d at 71).

79. Complaint ¶¶ 4-5, In the Matter of Intel Corp., No. 9341 (F.T.C. Dec. 16, 2009); Complaint at 10-12, New York v. Intel (D. Del. Oct. 12, 2009).

80. Herbert J. Hovenkamp, The Areeda-Turner Test for Exclusionary Pricing: A Critical Journal, U. Iowa Legal Studies Research Paper No. 14-16 (Apr. 2014), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2422120.

81. 475 U.S. 574 (1986).

82. 140 F. Supp. 1141 (D. Kan. 2001), aff’d, 335 F.3d 1109 (10th Cir. 2003).

83. ZF Meritor v. Eaton Corp., 696 F.3d 254, 350 (3d Cir. 2012) (Greenburg, J., dissenting).

84. Hovenkamp, supra note 80 at 11.

85. Id.

86. The one exception is Spirit Airlines, Inc. v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 431 F.3d 917 (6th Cir. 2005), where the plaintiff survived a motion for summary judgment.

87. United States v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 351 U.S. 377, 391 (1956).

88. United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1911).

89. United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 59 (D.C. Cir. 2001) ("[C]ourts routinely apply a similar balancing approach under the rubric of the ‘rule of reason.’"), cert. denied, 534 U.S. 952 (2001).