Public Law

Judges of Color: Examining the Impact of Judicial Diversity on the Equal Protection Jurisprudence of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

by KRISTINE L. AVENA*

This article was first published in the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly on November 1, 2018.

For too many people . . . law is a symbol of exclusion rather than empowerment.[1]

– Former Attorney

General of the United States, Eric Holder, 2002

Introduction

Article III, section 1 of the Constitution states, “[t]he judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”[2] This imperative provision of the Constitution establishes the judiciary branch and maintains the balance of powers within the federal government. At a time when the executive branch is banning religious minorities from traveling into the country[3] and stripping children away their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border,[4] the courts have become the last resort for many during this critical period of history. However, for much of America’s history, the legal system has been devoid of the compassion and empathy needed for judges to fully comprehend the impact of their decisions on ordinary people.[5] People of color, who have historically faced unique experiences because of racial discrimination and its legacy, are often victims of this need for empathy.[6] Thus, much like the fundamental equality that emanates from a diverse Congress,[7] the participation of diverse judges in the judiciary is vital to the assurance of fairness, legitimacy, and due process in decision-making.

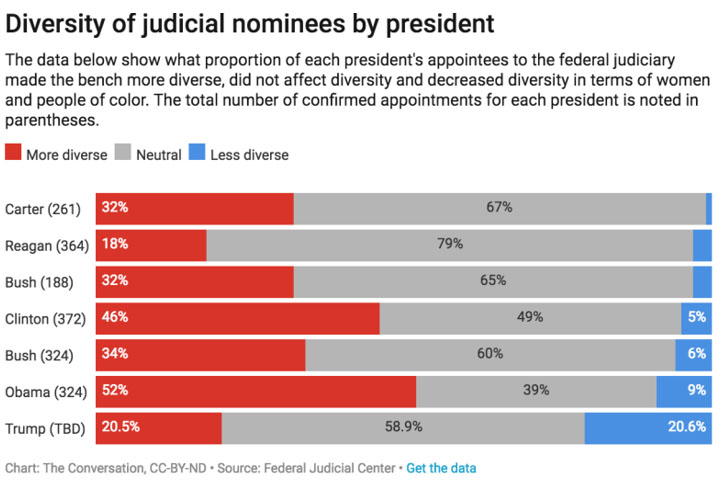

From slavery to civil rights to affirmative action, America’s history has been plagued with the issue of race. The federal bench is no exception. For almost two centuries, the highest court of the nation did not represent the public that it served. It was not until 191 years after the founding of America that the U.S. Supreme Court Bench enjoyed the presence of a diverse judge with Justice Thurgood Marshall.[8] Then in the 1970’s, due mainly to President Jimmy Carter’s initiative to appoint more minority judges, the racial composition of the federal judiciary began to diversify significantly.[9] However, while the number of minority judges increased in the past two centuries, the federal courts still do not reflect today’s society. The total composition of Article III judges currently includes: 3.4% Asians, 10.6% Hispanics, and 14.2% African Americans, compared to 72% Whites.[10] This composition is still less diverse than the current population of the United States, which is 6% Asian, 18% Hispanic, 12% African American, and 61% White.[11] In fact, a study by political science Professors Rorie Solberg and Eric N. Waltenburg reveals that the federal bench is becoming less diverse even as the United States is growing more diverse.[12]

| Exhibit A. Chart illustrating how previous Presidents have increased judicial diversity in the past two decades, but President Trump’s nominees are resulting in a less diverse judiciary. |

This article aims to determine how the presence of minority judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit impacts the Equal Protection doctrine.[13] The Ninth Circuit, which consists of Alaska, Arizona, California, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Northern Mariana Islands, Oregon, and Washington,[14] is the largest and most diverse federal appellate bench in the nation.[15] This article shows that a Ninth Circuit judge’s race is important in providing procedural and substantive contributions to the federal bench. Diverse judges use their life experiences to ensure that every person is heard and treated fairly, thereby instilling public confidence in the legitimacy of the court and educating their colleagues on the panel on the unique issues that minority groups encounter. However, this article also proves that race alone does not influence the court’s equal protection jurisprudence due to two major factors: the Ninth Circuit, as an appellate court, is bound by the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, and judges are committed to their duty to “faithfully and impartially” uphold the Constitution.[16]

This article applies the definition of a “minority” from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”).[17] According to the EEOC, a minority is “the smaller part of a group.”[18] These groups consist of: American Indian or Alaskan Natives, Asian or Pacific Islanders, Blacks, and Hispanics.[19] Currently, there are 13 racially diverse judges out of 48 judges on the Ninth Circuit: Carlos Tiburcio Bea, Patrick J. Bumatay, Consuelo María Callahan, Jerome Farris, Ferdinand F. Fernandez, Kenneth K. Lee, Mary H. Murguia, Jacqueline H. Nguyen, Richard A. Paez, Johnnie B. Rawlinson, A. Wallace Tashima, Kim McLane Wardlaw, and Paul J. Watford.[20] Approximately 27% of the 48 judges on this federal appellate bench are diverse, thus comprising of 3 African Americans, 4 Asians, and 6 Hispanics. Individually, these judges have unique life experiences that they bring to the bench – Judge Bea faced the threat of deportation,[21] Judge Nguyen fled her home country as a refugee during the Vietnam War,[22] and Judge Tashima was interned as a Japanese American during World War II.[23] This article addresses the impact that those distinctive life experiences bring to the bench.

I. The Equal Protection Doctrine

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states, “[n]o State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”[24] This study focuses on the Equal Protection Clause because it was designed to ensure that the Constitution protects minorities from prejudice in the political process.[25] When analyzing an equal protection claim, courts apply either a standard of heightened scrutiny, which includes both strict scrutiny and intermediate scrutiny, or they apply rational basis review.[26] Heightened scrutiny applies when a court has reason to “suspect” a classification reflects prejudice against a “discrete and insular” minority, rather than an informed policy choice.[27], [28]

There are two situations where one might see the impact of a judge’s race in evaluating equal protection claims. First, in order to pass strict scrutiny, a classification must be the least discriminatory means or narrowly tailored to serve a compelling interest.[29] Although there are prior examples of how the U.S. Supreme Court has applied this standard of review, its ambiguous and broad language gives judges much flexibility in its application. Second, if there is a classification that has not yet been established by law, judges have the authority to apply specific factors to determine whether a group constitutes a “suspect” class before applying strict scrutiny.[30] Judges have the discretion to assess the following factors: historical and current discrimination, political power, immutability of the characteristic, Congress’ sensitivity to the classification, and whether the trait correlates to an ability.[31]

II. Background and Methodology

Past research on judicial decision-making has focused on the impact of a variety of factors, but not on the impact of race alone. There are countless studies examining the role of intersectionality or gender on the federal bench,[32] decision-making in state courts or federal circuit courts as a whole,[33] and judicial voting patterns in favor or against a plaintiff or defendant.[34] These studies have found that a judge’s race only has an impact on particular issues. For example, Black judges are more sensitive to issues relating to racial discrimination because of their racial identity and firsthand experiences with racial discrimination.[35] In addition, Latino judges are more sympathetic in immigration cases, not due to racial discrimination, but rather, due to “the shared view of opportunities that life in the United States presented to their immigrant families.”[36] Similarly, Asian judges are also more sympathetic to immigrants, but because of their firsthand experiences with racism and xenophobia.[37] Among others, one consistent result is that minority judges are more sympathetic to civil rights issues such as gender and racial discrimination.[38]

The theory underlying this analysis is substantive representation, which posits that “when circumstances and discretion allow, public officials will act to benefit members of groups of which they are a part.”[39] A limitation of this theory with respect to appellate judges is that they are unelected and accorded life tenure, so they are not easily affected by public opinion.[40] Therefore, while this political insulation may lead some to do more to benefit their group, others may hide behind such safeguards and maintain the status quo. Additionally, Supreme Court scholars Harold Spaeth and Jeffrey Segal’s attitudinal model connects with this study’s focus on judicial decision-making. The attitudinal model claims that judges decide cases based on personal ideology rather than adherence to the law.[41] However, a major limitation of the attitudinal model is its assumption that ideology and legal interpretation are mutually exclusive in judicial decision-making. Merely because a judge’s ideology impacts one’s decision does not mean that their ideology conflicts with the law.

III. Findings Based on Personal Interviews

A substantial component of this study incorporates interviews with Ninth Circuit judges. Despite the apparent limitations of personal interviews, the judges’ insights are valuable in discerning the impact of race on their decision-making. I conducted interviews in person and telephonically, which lasted between 30 minutes to 1 hour. The interviews adhered to a specific structure. First, I informed the judges of my topic and granted anonymity if they desired. Second, I asked questions about their methods of persuasion and judicial decision-making. Third, we discussed the Ninth Circuit’s equal protection jurisprudence, with a particular focus on the opinions and dissents they had written. Fourth, I inquired about the judges’ specific life experiences and diversity on the federal bench.

i. Institutional Impact as a Federal Appellate Court

Appellate court decision-making is distinguishable from trial court decision-making due to the institutional structure of the three-judge panel.[42] Thus, it would be a disservice to discount the institutional dynamics of panels when evaluating the impact of race on decision-making. Research has consistently shown that appellate judges are more receptive to the preferences of the other members on the panel.[43] As such, the role of minority judges in these small panel sizes encourages impartiality “by ensuring that a single set of values or views do not dominate judicial decision-making.”[44] In addition, federal appellate court decisions are almost always unanimous.[45] Thus, due to the small size of the group, an atmosphere of collegiality, and panel unanimity, the role of minority judges in the Ninth Circuit can be a particularly vital one due to a greater potential to influence other nonminority judges on the panel.

When meeting with the Ninth Circuit judges individually, I asked, “[w]hat methods do you use in persuading your colleagues on the panel when there are disagreements?” One judge stressed the importance of being knowledgeable about her colleagues in order to persuade them more effectively.[46] For instance, it was helpful to know what they have written, published, and were interested in. Another judge adopted a more formalistic approach and described how he used a “method of analysis” when persuading his colleagues.[47] A third judge noted that the panels try to reach “consensus whenever possible” when they confer.[48] Finally, one judge emphasized that interrelationships were important, but ultimately it came down to the issues.[49] An interesting commonality I found amongst the judges was the respect they shared for one another. Despite the disagreements amongst the judges in terms of interpreting the law, their interactions illustrate the collegiality and impartiality within the Ninth Circuit.

ii. Impact of Party Affiliation on Judges’ View of their Judicial Role

Diversity on the bench can be extremely partisan between Republicans and Democrats. Although the Constitution permits the President to appoint and the Senate to confirm federal judges,[50] politics influences the choices for the federal bench.[51] This delicate intersection between the law, judicial activism, and political affiliation is significant because it can mean the difference between a confirmation or no confirmation.[52]

After interviewing two Ninth Circuit judges who were appointed by Republican Presidents and two judges who were appointed by Democratic Presidents, I found that judges of each party stressed the importance of remaining impartial in order to apply the law faithfully. However, I also noticed that party affiliations influenced these judges’ ideas about what it meant to “apply the law faithfully.”[53] Specifically, Republican-appointed judges seemed to view the judicial branch as an extension of the executive and legislative branches, and emphasized the importance of judicial deference to those branches accordingly.[54] In contrast, Democratic-appointed judges expressed that they were more likely to view the other branches’ actions critically and emphasized their roles as public servants, not as guardians of the determinations of the other branches.[55]

Furthermore, I found that despite the adverse backgrounds of certain diverse Ninth Circuit judges, they were committed to applying facts to the law rather than advocating for their idea of justice. For instance, Judge Nguyen, who came to the U.S. as a refugee from the Vietnam War, stated that her obligation is to “faithfully apply the law regardless of who the litigants are, which includes rich or poor, men or women, and people of any ethnic origin or nationality.”[56] Additionally, Judge Murguia, who grew up in Kansas with six siblings, had a low socioeconomic status, and was raised by Mexican immigrants, admitted that the hardest thing she does as a judge is rule contrary to her personal opinions.[57] She highlighted the necessity of separating her personal viewpoints from the law when reaching a decision and reiterated her judicial responsibilities according to the oath she took under the Constitution.[58]

Another remarkable judge is Judge Tashima, a 1996 President Bill Clinton appointee.[59] Given his personal experience of living in an internment camp during World War II,[60] Judge Tashima acknowledged the impact that his racial identity and historical mistreatment have made on his decision-making.[61] In a journal article describing his experience in a Japanese American internment camp, Judge Tashima wrote:

Because we are all creatures of our past, I have no doubt that my life experiences, including the evacuation and internment, have shaped the way I view my job as a federal judge and the skepticism that I sometimes bring to the representations and motives of the other branches of government.[62]

This critical eye to government action is further evidenced by Judge Tashima’s opinions on equal protection claims. For instance, he has criticized the government’s race-based actions “in the name of science and medicine.”[63] He has also written a significant number of equal protection opinions since being appointed, compared to his Ninth Circuit colleagues. Judge Tashima’s political beliefs and strong connection to his racial identity represent a telling example of how a minority judge’s experiences have informed his decision-making.

iii. Impact of Race on Judicial Decision-making

When asked, “[w]hat role, if any, do you think your ethnic background plays in your decision making,” several of the judges became defensive. One judge went so far as to say, “race is irrelevant” to the benefit versus burden analysis in equal protection claims.[64] Another judge stressed that she is not “agenda-driven,” and judges work hard to be impartial.[65] Nevertheless, both judges acknowledged that race does have an impact in particular situations. One judge admitted that judges who have had experiences with police officers or the criminal justice system “cannot help but be influenced by where they come from.”[66] Furthermore, a judge stated that “the door might easily open to believing a minority discrimination claimant by a member of that same minority,” and that it is a “human fallibility.”[67] Finally, another judge noted that her unique experiences have “given her more context” and allowed her to see the law in a different lens, but she is uncertain that this perspective has affected her decision-making.[68]

The judges’ reluctance to consider the impact that their diverse life experiences might have on their decisions can be attributed, at least in part, to the position of the federal appellate court in comparison to the U.S. Supreme Court. Hierarchically, the Ninth Circuit is positioned below the U.S. Supreme Court, so Ninth Circuit judges have a natural tendency to refrain from exhibiting any disagreement or discontent about the precedents set forth by the highest court of the nation. Unsurprisingly, every judge I interviewed stressed that they must abide by the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Likewise, the Ninth Circuit is also placed in a unique position compared to the federal district courts. For example, in immigration cases, the Ninth Circuit reviews cases from the Immigration Court and the Board of Immigration Appeals with a deferential standard of review. This respectful deference was present in all the interviews I conducted with Ninth Circuit judges and exemplifies the constraints that limit appellate court judges in their decision-making. Therefore, Ninth Circuit judges must accord proper deference not only to the U.S. Supreme Court, but also to the fact-finding responsibilities of the federal district courts. This unique position greatly inhibits federal appellate judges from exercising their discretion.

Despite judges’ adherence to impartiality and precedent, a common thread among the interviewed judges was the value they placed on professional experiences, education, and overcoming adversity in helping them obtain their prestigious post. For instance, Judge Callahan, who is the first lawyer in her family, highlighted that “education is the great equalizer.”[69] Moreover, Judge Murguia expressed a sense of triumph when describing how the American dream came true for her and her siblings.[70] She reiterated this pride during her confirmation hearings to become a Ninth Circuit judge and wrote, “your intellect and your character contribute in defining who you are, but I also think that your heritage and your culture is key, and that’s what makes the person who is the judge.”[71]

Finally, Judge Nguyen highlighted that even though she feels a “special responsibility” as the first Asian American judge to serve in a federal appellate court, she stressed that this responsibility does not “translate into bending or shaping the law in favor of any group.”[72] However, she did express that she takes her responsibility seriously in “being a role model, mentor, accessible to the community” and “maintaining equal opportunities and professional advancement for individuals who have been disadvantaged in the past.”[73] Therefore, while the judges were uncertain about the effect that race plays in their thought processes, their responses highlight the connection they feel to overcoming substantial obstacles while growing up. This powerful connection to their self-worth is a significant and unique aspect of who they are as judges of color in one of the highest courts in the nation.

IV. Common Themes

Despite the inherent tension of discussing race as a federal judge, some themes remain present. First, the judges exhibited a willingness and excitement to speak about the impact of their professional and life experiences on their career, but not on their decision-making. From being the first in their family to become an attorney, to competing as a basketball player in the Olympics, these judges were eager to share their ability to overcome adversity. As judges of color, they understandably displayed a sense of pride in excelling in their career despite the obstacles that minorities encounter within the legal profession.

Second, while the judges did not explicitly discuss the impact of race in their decision-making, they implied that having a diverse bench positively impacts the equal protection doctrine in specific situations. When asked, “[i]n which way, if any, do you think the presence of minority judges improves the court’s equal protection jurisprudence,” the Ninth Circuit judges mainly alluded to cases involving racial discrimination and criminal justice. For example, one judge noted that he would take race into account when it was “prudent[ial]” to do so.[74] He provided an example of having an informant of the same race as a gang member in an FBI investigation in order to serve a compelling government interest.[75] Judge Callahan highlighted the benefit of having diverse judges when analyzing whether a comment may be offensive to a particular group because these judges can provide a different lens to the situation based on their personal experiences with discrimination.[76] During Judge Nguyen’s confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, she told members that “her life experience . . . gives [her] an appropriate sense of humility when [she] review[s] the facts of each case. [She] ha[s] an understanding and appreciation of how intimidating the court system can be.”[77] She also highlighted that diversity is especially imperative at the circuit court level because the structure of panels creates a more improved “end product . . . as a result of that dialogue.”[78]

Finally, and most importantly, the interviews and opinions both suggest that while racial diversity matters, the law matters more. Although the judges articulated that racial diversity plays a significant role in the court’s reputation with the public, they consistently reiterated their duty to faithfully apply the law. When addressing the value of diversity on the bench, Judge Nguyen expressed that it is “critically important” to have a judiciary that is reflective of the population that we serve.[79] She explained that the Ninth Circuit’s credibility as a public institution depends on the trust that the public has in the judges’ decision-making.[80] Thus, if a judiciary is comprised of all white men from corporate law firms, she explained, this would erode the public’s trust.[81] This advantageous public perception is unique to diverse judges and exemplifies the circumstances, although limited, in which a diverse judge can incorporate his or her experiences into judicial decision-making. It coincides with Judge Nguyen’s belief that “diversity is absolutely critical to the viability of the judiciary as an institution.”[82] Conversely, even though judicial diversity is imperative to the credibility of the bench, the interviews and case law tend to prove that the law influences minority judges more than their experiences. This is perhaps due to the tremendous obligation that diverse judges feel to implement the law impartially.[83]

Conclusion

The current Administration has exhibited an indifference to the value that a diverse judiciary brings to a legitimate government structure.[84] Because judicial diversity is not a priority on President Donald Trump’s political agenda, the number of racial minorities on the bench may decline.[85] This detrimental shift against judicial diversity is evidenced in President Trump’s recent federal judicial nominees, which have been 91% white and 81% male.[86] President Trump’s choice of nominees starkly contrasts President Barack Obama’s legacy of diversifying the courts, as President Obama “was the first President for whom nontraditional nominees comprised a majority (69%) of all those he appointed as circuit court judges.”[87] In contrast, President Trump’s nominees to the Ninth Circuit,[88] along with his hostile perception of the federal circuit court,[89] foreshadows a possible unfortunate decrease in judicial diversity in the coming years.

By demonstrating the invaluable contributions that judicial diversity brings to the judicial branch, this article suggests that failing to diversify judicial appointments comes at a cost. Although judicial diversity does not play a significant role in influencing the equal protection doctrine, the value that minority judges bring to the federal judiciary should not be overlooked. Minority judges exhibit a “heightened awareness” of the issues that disadvantaged people face.[90] Due to this special perspective, diverse judges are more able to fully comprehend the impact of their decisions on the people they serve and give credence to a “color-blind” Constitution.[91] As judges of color, they bring a greater quality to the Ninth Circuit that was absent for centuries. Their ability to faithfully interpret the law, despite its tension with their closely-held personal beliefs, adds a vital layer of legitimacy and democracy to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

* J.D. Candidate 2019, University of California, Hastings College of the Law; B.A. 2016, Chapman University. A special thank you to Professor Dorit Reiss, the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly editors, and my fiancé for their invaluable feedback. I am grateful to the four Ninth Circuit judges who shared their experiences and knowledge with me. This article is dedicated to little girls who dream of becoming a judge one day.

[1] Eric H. Holder, Jr., Fifty-Third Cardozo Memorial Lecture: The Importance of Diversity in the Legal Profession, 23 Cardozo L. Rev. 2241, 2247 (2002).

[2] U.S. Const. art. III, § 1.

[3] Josh Gerstein, Appeals Court Rules Against Trump Travel Ban 3.0, Politico (Dec. 22, 2017), https://www.politico.com/story/2017/12/22/trump-travel-ban-appeal-block-317892.

[4] Salvador Rizzo, The Facts About Trump’s Policy of Separating Families at the Border, Wash. Post (Jun. 19, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2018/06/19/the-facts-about-trumps-policy-of-separating-families-at-the-border/?utm_term=.2524c5c5f7f7.

[5] Jill D. Weinberg & Laura Beth Nielsen, Examining Empathy: Discrimination, Experience, and Judicial Decision-making, 85 S. Cal. L. Rev. 313, 351 (2012).

[6] Id. at 326, 350–51.

[7] Sheryl Estrada, The 115th Congress Not a Model for Diversity, Diversity Inc. (Jan. 4, 2017), https://www.diversityinc.com/news/115th-congress-not-model-diversity; James Jones, Racial Representation: A Solution to Inequality in the People’s House, The Hill (May 10, 2017), http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/civil-rights/332790-racial-representation-a-solution-to-inequality-in-the-peoples.

[8] DeNeen L. Brown, LBJ’s Shrewd Moves to Make Thurgood Marshall the Nation’s First Black Supreme Court Justice, Wash. Post (Oct. 2, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/10/02/lbjs-shrewd-moves-to-make-thurgood-marshall-the-nations-first-black-supreme-court-justice/?utm_term=.44ae6dded661.

[9] Susan B. Haire & Laura P. Moyer, Diversity Matters 3–4 (2015).

[10] Goodwin Liu, et al., A Portrait of Asian Americans in the Law 24 (Yale Law School & National Asian Pacific American Bar Association 2017), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3045905.

[11] Kaiser Fam. Found., Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on the Census Bureau’s March Current Population Survey (CPS: Annual Social and Economic Supplements) (2017), https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

[12] Rorie Solberg & Eric N. Waltenburg, Trump’s Presidency Marks the First Time in 24 Years That the Federal Bench Is Becoming Less Diverse, The Conversation (Jun. 11, 2018), https://theconversation.com/trumps-presidency-marks-the-first-time-in-24-years-that-the-federal-bench-is-becoming-less-diverse-97663; See Exhibit A for judicial diversity chart.

[13] For purposes of this study, the terms “minority” and “diverse” judge are used interchangeably.

[14] Map of the Ninth Circuit, https://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/content/view.php?pk_id=0000000135.

[15] Russell Wheeler, The Changing Face of the Federal Judiciary, Brookings Inst. 4–5 (2009).

[16] See 28 U.S.C.A. § 453 (West 1990) (stating the Judicial Oath “I, _________, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent upon me as _________ under the Constitution and laws of the United States. So help me God.”).

[17] This article also uses the term “diverse” to describe judges who fall within the EEOC’s definition of a racial minority.

[18] EEO Terminology, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/eeo/terminology.html.

[19] Id.

[20] See the Judges of this Court in Order of Seniority,United States Courts for the Ninth Circuit, https://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/content/view_seniority_list.php?pk_id=0000000035; A.B.A. Standing Committee on Minorities in the Judiciary, A.B.A. Directory of Minority Judges (4th ed. 2008).

[21] See David Lat, Benchslap of the Day: Say My Name, Say My Name, Above the Law (Feb. 16, 2012, 6:18 PM)

[22] See Casey Tolan, How Jacqueline Nguyen Went From a Vietnamese Refugee to a Potential Supreme Court Nominee, Splinter News(Feb. 18, 2016, 4:45 PM) https://splinternews.com/how-jacqueline-nguyen-went-from-a-vietnamese-refugee-to-1793854865.

[23] See Sakura Kato, Judge A. Wallace Tashima: A Judge Who Looks Like Us, Discover Nikkei (Aug. 6, 2014) http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2014/8/6/judge-tashima/.

[24] U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1-Citizens.

[25] United States v. Carolene Prod. Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152 n.4 (1938).

[26] City of Cleburne, Tex. v. Cleburne Living Ctr., 473 U.S. 432, 440 (1985).

[27] Carolene Products. Co., 304 U.S. 144.

[28] Rational basis review, on the other hand, allows a court to uphold a classification as long as any rational legislator could think the classification could advance any legitimate purpose.

[29] Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 326 (2003).

[30] Cleburne Living Ctr. Tex., 473 U.S. at 440.

[31] Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677, 684–88 (1973).

[32] Todd Collins & Laura Moyer, Gender, Race, and Intersectionality on the Federal Appellate Bench, 61 Pol. Res. Q. 219–227 (2008).

[33] Jonathan P. Kastellec, Panel Composition and Voting on the U.S. Courts of Appeals over Time, 64 Pol. Res. Q. 377–391 (2011) [hereinafter Kastellec 2011]; Jonathan P. Kastellec, Racial Diversity and Judicial Influence on Appellate Courts, 57 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 167–183 (2013) [hereinafter Kastellec 2013].

[34] Jeff Yates, ‘For the Times They Are A-Changin’: Explaining Voting Patterns of U.S. Supreme Court Justices through Identification of Micro-Publics, 28 Byu J. Of Pub. L. 117–143 (2013).

[35] Susan B. Haire & Laura P. Moyer, Diversity Matters 18–22 (2015).

[36] Id. at 25.

[37] Josh Hsu, Asian American Judges: Identity, Their Narratives, & Diversity on the Bench, 11 Asian Pac. Am. L.J. 92, 106, 112 (2006).

[38] Sean Farhang & Gregory Wawro, Institutional Dynamics on the U.S. Court of Appeals: Minority Representation Under Panel Decision Making, J. L. Econ. & Org. 303 (2004).

[39] Todd Collins & Laura Moyer, Gender, Race, and Intersectionality on the Federal Appellate Bench, 61 Pol. Res. Q. 220 (2008).

[40] Kastellec 2013, supra note 33, at 168–69.

[41] Howard Gilman, What’s Law Got to do With It? Judicial Behavioralists Test the Legal Model of Judicial Decision Making, 26 L. & Soc. Inquiry 467 (2001).

[42] See generally Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, Ninth Circuit Rules, Circuit Advisory Committee Notes.

[43] Susan B. Haire & Laura P. Moyer, Diversity Matters 88 (2015).

[44] Sherrilyn A. Ifill, Racial Diversity on the Bench: Beyond Role Models and Public Confidence, 57 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 405, 411 (2000).

[45] Sean Farhang & Gregory Wawro, supra note 38.

[46] Telephone Interview with Judge Consuelo M. Callahan, Ninth Circuit Judge (Nov. 7, 2017).

[47] Confidential Interview with Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Oct. 17, 2017).

[48] Interview with Judge Mary H. Murguia, Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Nov. 15, 2017).

[49] Telephone Interview with Judge Jacqueline H. Nguyen, Ninth Circuit Judge (Dec. 5, 2017).

[50] See U.S. CONST. art. II, § 2, cl. 2.

[51] Opinion, Judges Shouldn’t Be Partisan Punching Bags, N.Y. Times, Apr. 8, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/08/opinion/judicial-independence.html.

[52] See Carl Hulse, G.O.P. Blocks Judicial Nominee in a Sign of Battles to Come, N.Y. Times (May 19, 2011), http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/20/us/politics/20congress.html.

[53] See 28 U.S.C.A. § 453 (West 1990).

[54] But see City and County of San Francisco v. Trump, 9th Cir., Aug. 1, 2018, No. 17-17478 (2018) WL 3637911 (two Democratic-appointed nonminority judges holding that executive branch may not withhold federal grants from sanctuary cities without congressional authorization and the sole Republican-appointed minority judge dissenting that the case is not ripe for review).

[55] I offer these conclusions with skepticism due to the extremely small sample size of four judges.

[56] Telephone Interview with Judge Jacqueline H. Nguyen, Ninth Circuit Judge (Dec. 5, 2017).

[57] Interview with Judge Mary H. Murguia, Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Nov. 15, 2017).

[58] Id.

[59] See The Judges of this Court in Order of Seniority, supra note 20.

[60] A Judge Who Looks Like Us, supra note 23.

[61] A. Wallace Tashima, Play It Again, Uncle Sam, 68 L. & Contemp. Probs. (2005).

[62] Id.

[63] Mitchell v. Washington, 818 F.3d 436, 444 (9th Cir. 2016).

[64] Confidential Interview with Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Oct. 17, 2017).

[65] Telephone Interview with Judge Consuelo M. Callahan, Ninth Circuit Judge (Nov. 7, 2017).

[66] Id.

[67] Confidential Interview with Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Oct. 17, 2017).

[68] Interview with Judge Mary H. Murguia, Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Nov. 15, 2017).

[69] Telephone Interview with Judge Consuelo M. Callahan, Ninth Circuit Judge (Nov. 7, 2017).

[70] Judge Murguia, Video Oral History with Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, (Jul. 7, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMX1wvtfgoM.

[71] See Responses of Mary H. Murguia Nominee to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit to the Written Questions of Senator Jeff Sessions.

[72] Telephone Interview with Judge Jacqueline H. Nguyen, Ninth Circuit Judge (Dec. 5, 2017).

[73] Id.

[74] Confidential Interview with Ninth Circuit Judge, in San Francisco, Cal. (Oct. 17, 2017).

[75] Id.

[76] Telephone Interview with Judge Consuelo M. Callahan, Ninth Circuit Judge (Nov. 7, 2017).

[77] Kitty Felde, Southern California Judge Questioned by Senate Judiciary Committee, So. Cal. Pub. Radio (Nov. 2, 2011), http://www.scpr.org/news/2011/11/02/29683/southern-california-judge-questioned-senate-judici/.

[78] Telephone Interview with Judge Jacqueline H. Nguyen, Ninth Circuit Judge (Dec. 5, 2017).

[79] Id.

[80] Id.

[81] Id.

[82] Id.

[83] See generally Code of Conduct for United States Judges, at Canon 2; 28 U.S.C.A. § 453 (West 1990).

[84] See generally Carrie Johnson, One Year In, Trump Has Kept A Major Promise: Reshaping the Federal Judiciary, NPR (Jan. 21, 2018), https://www.npr.org/2018/01/21/579169772/one-year-in-trump-has-kept-a-major-promise-reshaping-the-federal-judiciary.

[85] Catherine Lucey & Meghan Hoyer, Trump Choosing White Men as Judges, Highest Rate in Decades, Chi. Trib. (Nov. 13, 2017), http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/ct-trump-blacks-judges-20171113-story.html.

[86] Id.

[87] Barry J. McMillion, U.S. Circuit and District Court Judges: Profile of Select Characteristics, Cong. Res. Serv., Summary (2017).

[88] Judicial Vacancies and Nominations, United States Courts for the Ninth Circuit (Aug. 21, 2018), https://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/content/view_db.php?pk_id=0000000899.

[89] Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), Twitter (Jan. 10, 2018, 6:11 AM), https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/951094078661414912; id. at (Apr. 26, 2018, 3:20 AM), https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/857177434210304001; id. at (Apr. 26, 2018, 3:38 AM), https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/857182179469774848.

[90] Kastellec 2013, supra note 33.

[91] Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 559 (1896) (Harlan, J., dissenting).